This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H & my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H & in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandmother Channah Freidel Bas Sarah

-My great aunt Rivkah Bas Etta

-Miriam Liba Bas Devora

-Aviva Malka Bas Leah

-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamah of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus.

בס”ד

כִּי תָבוֹא ~ Ki Savo

לעלוי נשמת קיילא רות בת בונם טוביה

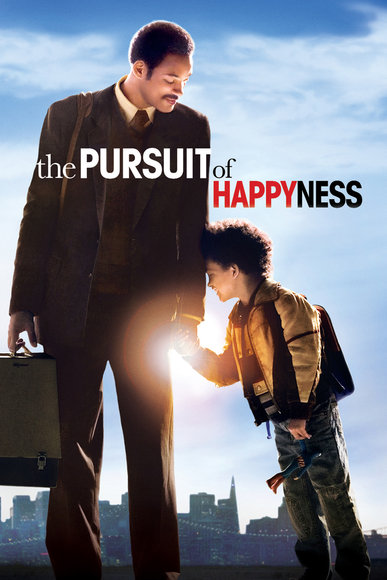

“Pursuit of Happiness”

Deuteronomy.28.35

Deuteronomy.28.47

Deuteronomy.28.56

Deuteronomy.28.65

The focal point of Parshas Ki Savo is the second infamous Tochachah, or passage of Admonition [Devarim 28]. In this passage, Moshe Rabbeinu portrays the gravity of the B’nei Yisrael’s covenant with Hashem and His Torah in the form of a long and frightening discourse describing the horrible and disturbing curses that will befall the B’nei Yisrael should they forsake the Torah after they enter the Promised Land, G-d forbid. However, since this general concept should already be understood from the first Tochachah back in Parshas B’Chukosai [Vayikra 26], it would pay for us to understand the differences are between the two passages.

Indeed, many M’forshim (commentators) have written on this topic, suggesting possible discrepancies. The Ramban points out that the first Tochachah was an allusion to the exile following the First Temple era while this one refers to the exile following the Second Temple era. The first Tochachah, many point out, is evidently connected to Shmitah, the agricultural Sabbatical year of the land, whereas this one does not seem to have any such connections. Another difference noted by the commentators is that the first Tochachah speaks to the B’nei Yisrael in the plural, while this one addresses them in singular, and many suggestions might be offered as to why that might be.

However, the difference we’re going to focus on here is that while the curses of the first Tochachah are apparently a consequence for merely failing to faithfully follow Hashem’s Torah, this Tochachah conspicuously adds that its curses will occur [Devarim 28:47], “Tachas Asheir Lo Avadta Es Hashem Elokecha B’Simchah U’V’Tuv Leivav B’Rov Kol”-“On account [lit., in place of] that you did not serve Hashem your G-d with happiness and with goodness of heart when all was [relatively] abundant.” In other words, evidently, according to this Tochachah, the curses are not a result of not serving G-d or fulfilling His Torah. Perhaps the B’nei Yisrael really are engaging in service of Hashem to some degree, however, they are just not doing so with happiness and graciousness.

Now, in light of what we know from the first Tochachah, this Tochachah changes the Torah’s expectations of us entirely. Indeed, there is a major difference between not fulfilling the Torah at all and not fulfilling it in happiness. The standard to avoid the “curses” has certainly gotten higher. It would not be enough to serve G-d and perform His commandments. That would be a given. To avoid the curses of the Tochachah, we have to do all of the above, but with happiness.

But at the outset, it seems rather demanding. Should we necessarily be held to such a standard? Is it fair for the Torah to demand that we internally feel a certain emotion when we serve G-d assuming that we might happen to not naturally be feeling that emotion? If nothing particularly pleasant or thrilling happened to make me happy, should I be cursed if I’m not serving Hashem with this happiness? What if one’s life, G-d forbid, is reasonably challenging making it hard for him to be happy? What if one doesn’t get the things he wants out of life, and he is therefore not happy? What if one is legitimately distressed or pained over the particular conditions of his life situation? What if he is performing the commandments, but for any reason, he is just not particularly happy to do so? Do we just tell him, “You’re gonna do it, and you’re gonna like it, or else”? There is a world of people who struggle in life, and many of these people, regardless of their situation, stick it out and observe Hashem’s Torah as He commanded. Would it not be honorable and fair enough that such individuals get through each day, faithfully proceeding in their service of G-d, even if they’re not internally happy as they do so? How could anyone expect anything more of them? How can we be expected to feel a certain emotion “on command” and control whether or not we experience the emotion of Simchah described here?

Another unique detail found in this particular Tochachah is that it features a particular phrase and imagery multiple times which does not appear often elsewhere in the Torah, “Kaf Regel,” literally, the sole of the foot.

At one point in the Tochachah, the Torah writes [28:35] “Yakchah Hashem B’Shechin Ra Al HaBirkayim V’Al HaShokayim Asheir Lu Suchal L’Heirafei MiKaf Raglecha Ad Kadkadecha”-“Hashem will hit you with foul [lit., evil] boils on the knees and on the thighs, that which you will not be able to heal, from the sole of your foot until your crown [head, scalp].” Later, the Torah states [28:56], “HaRakah Vecha V’HaAnugah Asheir Lo Nisesah Chaf Raglah HaTzeig Al HaAretz MeiHis’aneig U’Meiroch Teira Einah B’Ish Cheikah U’Vivnah U’V’vitah”-“The tender woman among you and the delicate one who had never tried to set the sole of her foot on the ground because of [her] delicacy and tenderness will turn her eye evil [become greedy] against the man [husband] of her bosom, and her son, and her daughter.” And finally the Torah says [28:65], “U’VaGoyim HaHeim Lo Sargi’a V’Lo Yihiyeh Mano’ach L’Chaf Raglecha…”-“And among those nations, you will not be tranquil, and there will not be rest for the sole of your foot…”

Apparently, this expression “Kaf Regel” is representative of some recurring theme in this Tochachah. But what is the significance of the “sole of the foot” and what would the meaning of this theme here?

In our first question, we challenged the idea that it is fair for Hashem to expect us to not only serve Him, but to serve Him with happiness. We argued, firstly, against the notion that man truly has the choice to control his emotions and be happy “on command” at all, and secondly, the notion that man could even do so despite particularly trying circumstances. The simple assumption we made is that people cannot merely control their emotions. Thrilling life events, our successes, enjoyable sensory experiences and the like all contribute to making a person happy. Otherwise, what else is there to be happy about? Perhaps, the very service of G-d should make us happy? Okay, maybe—if a person enjoys that kind of thing. But even assuming he does, that doesn’t mean that other events or experiences in one’s life will not likely rain on the parade and interrupt the happiness even if man is engaged in the enjoyable service of Hashem. Our emotions are influenced by a lot of stimuli. What, then, can anyone expect from us, from an emotional standpoint?

Yet, the Torah tells us we must serve Hashem with Simchah, that, in fact, we are expected to do so. The assumption that the Torah is making, then, is that not only is it possible for us to control our emotions and to choose to be happy, but that we can do so despite trying circumstances. The next question, then, is: How? If the challenges of life are overpowering our positive experiences—even the experience of engaging in Torah, how do we obtain this “Simchah” with which we’re apparently required to serve Hashem? Where does it come from?

The answer to this question might lie in the subtle theme of Kaf Regel, the sole of the foot. What is the meaning of this symbol, the sole of the foot?

Above, we quoted three references to the sole of the foot that are found in the Tochachah, the first, that boils will cover even the sole of the foot. The second reference was that the tender woman whose sole of her foot never touched the ground will turn against her family. The third reference was that among the nations of the world, there will be no respite for the sole of the foot, that in the exile, the B’nei Yisrael will not be able to rest its foot. So, what is the meaning of the sole of the foot?

The last of the three references to the sole of the foot contains a striking parallel to the very first verse in which the expression “sole of the foot” was used in the Torah. If one looks back in Parshas Noach after the Flood, when Noach sends out the Yonah (dove) to find dry land, the Torah tells us, with the same phraseology as in our Tochachah [Bereishis 8:9], “V’Lo Matz’ah HaYonah Mano’ach L’Chaf Raglah…”-“And the dove did not find rest for the sole of its foot…”

What this parallel tells us is that the effect that the curses would have on us, should they happen G-d forbid, is represented by the effects of the Flood on the dove. When we’re sent to exile, says the Tochachah, there will be no Mano’ach or “rest” among the nations, rather, like the exhausted dove wandering and flapping around over flood waters, there will be no place to simply stop and take a breather.

In his Shabbos poem, Yom Shabbason (Day of Rest), R’ Yehudah HaLevi takes this exact imagery of the dove looking for rest and uses it to portray how during the week, we fly around tirelessly until finally Shabbos arrives and provides Mano’ach, that rest for us.

With the same imagery utilized in the Tochachah, we could suggest that Kaf Regel, the sole of the foot, represents our footing in this world, and Mano’ach, the place of rest, represents our ability to simply stand and exist while we’re here. Together, these variables are symbolic of the bare necessities of life that we normally take for granted; the ability to stand on our feet and have a place at which to retire for the night, the ability to put food on our tables, to have simple bodily functioning, etc. When we’re blessed to have Mano’ach, a place of rest, just like on Shabbos, we achieve a sense of Menuchah. What does it mean to have Menuchah? Menuchah, though tanslated normally as rest, actually has a deeper connotation, as it refers to the state of contentment. That means that no matter what project I was working on during the week, when Shabbos comes along, I have to have this Menuchah—to stop worrying about that project, to calmly accept and be humbly content with whatever situation G-d has left me. It means that even if my life situation is difficult and trying, I still have to stop what I’m doing and appreciate the good that I do have, because in reality, G-d owes me nothing and every bit He gives me is a gift. Shabbos is merely the weekly reminder that we must take nothing for granted, and rather, thank Hashem for the countless good that He has left us, and to remember that goodness as we serve Him.

In that vein, we could suggest that in order to reach true Simchah, that explosion of enduring happiness, we need to first reach the level of Menuchah, where we’re simply content with what we have. This idea may be alluded to in another famous Shabbos Zemer (song), Menuchah V’Simchah (authored by an individual named Moshe in 1545), that in that very order, we must first achieve Menuchah—by accepting and appreciating what we have—and then, we can achieve true Simchah, a happiness that comes not from our external situation, but from within ourselves.

The problems arise when we fail to appreciate the Man’oach, the ability to rest the soles of our feet, and withhold ourselves from having Menuchah when that breather has been provided for us. When we don’t appreciate what we have, we not only fail miserably to attain Simchah, but Hashem takes note of our ungratefulness and subsequently removes the Man’oach that we’ve taken for granted. This point is the message of the Tochachah. The Galus, or exile, described in the Tochachah, based on everything we’ve discussed, is likened to not having a sense of Shabbos, meaning no Menuchah. The Menuchah is virtually unattainable because, at that point, the simple necessities which we took for granted and did not rejoice in, all of a sudden, are put out of our reach.

And as the Tochachah warns, Hashem can bring boils to the soles of our feet, and it’ll pain us to even stand. Furthermore, the Tochachah says, as we quoted earlier, that the once tender woman who did not take advantage of the rest provided for the sole of her foot will turn on her family, reflecting the ultimate selfishness and lack of appreciation for what she has. And finally, like the Yonah, we will be flying around with nowhere to rest—we will have completely lost our state of Menuchah, our footing in this world.

In truth, the pursuit of happiness, as most people imagine it is really just that, nothing more than an imagination. People spend their lives pursuing, but they fail to find the circumstances that perfectly match their idea of what should be making them happy. These people may proceed to keep Hashem’s Torah, but they will not do so with the required degree of happiness if they allow their situation to determine for them whether or not they should be happy. On the other hand, truly happy people will continuously realize that to be happy really is their choice; that even in life’s most trying circumstances, there is something G-d gave them that is worth appreciating, and that we all must therefore develop this appreciation and allow it to manifest itself throughout our service to Him.

This Sunday will be my sister Kayla Rus’s first Yahrtzeit (anniversary of her passing). Simply put, she was a happy person. Among all her incredible virtues, her Simchas HaChaim—her appreciation of life in all the eighteen years she was blessed to have it, was something that shined through even as every reason to be happy or even simply content with life was quickly taken away from her during her battle with cancer. Even when the “place of rest” was pulled out beneath the “sole of her foot,” she maintained her gracious smile and thanked Hashem. If you’d ask her, she was happy, because she did not take her life for granted. Each day, she humbly and modestly accepted was another precious gift. Her happiness came, not from her external situation, but from within, and subsequently remained with her as she was escorted to the Next World where being happy would no longer have to be a test or a matter of choice. Such a soul should merit only further Aliyah (elevation).

In the end, how G-d can expect us to serve Him with happiness, in this light, is really no longer a question at all. On the other hand, how we can withhold ourselves from being grateful and serving Hashem in happiness despite the abundance G-d does constantly provide us at every moment of our lives is truly the greatest wonder. We cannot lose track of the gifts G-d gives us each day because of the fabrication we know as the “pursuit of happiness.” When we appreciate the simple rest provided for the soles of our feet, true and enduring happiness should and will shine forth from within.

May we all be Zocheh to appreciate all the good that Hashem constantly does for us, be content and subsequently happy with our lot, serve Hashem with that true, enduring happiness, and Hashem should rejoice with us as well as we bask in eternal happiness with the coming of the Geulah in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Josh, Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.