| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben Yosef A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta-MY BROTHER: MENACHEM MENDEL SHLOMO BEN CHAYA ROCHEL -HaRav Gedalia Dov Ben Perel -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Yechiel Baruch HaLevi Ben Liba Gittel -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

וַיִּגַּשׁ ● Vayigash

● Why does Hashem tell the excited and ecstatic Yaakov not to be afraid? When Yaakov and Yosef reunite, why does the Torah say “and he appeared to him”? ●

“And He Appeared – Yosef’s Magic Act”

After a long twenty-two years in the clutches of his personal Egyptian Exile, Yosef HaTzaddik would become the viceroy to Pharaoh, reach peaceful terms with his brothers, and finally be reunited with his father Yaakov Avinu ending Yaakov’s long period of spiritual and emotional agony. When Yaakov heard that Yosef was still alive and he noticed the wagons which Yosef had sent home revealing that he was, indeed, alive and well, Yaakov was ecstatic and fully prepared to go down to Egypt to join his son once again.

If all of the above is true, what happened next is a bit strange.

“Have No Fear!”

Before Yaakov made his descent, Hashem appeared to him in an ominous, night vision, telling him not to be afraid to go down to Egypt, reassuring him that He would return home with him.1 The line, “Al Tira”-“Don’t be afraid” implies that there was some reason that Yaakov may have been or should have been afraid. However, if one looks at the flow of the Pesukim2, before G-d showed up, Yaakov was clearly elated, showing no visible signs of dread or even nervousness about going down to Egypt; as long as he could see Yosef, he was happy to go.

Accordingly, one has to wonder: What new news could have possibly caused such a sudden damper on the tidings of Yosef’s survival, triggering this abrupt transition from bliss to fear in Yaakov? If the text itself indicated, before G-d said anything, that Yaakov was excited and ready to go to Egypt, how is it that the apparently new “anxiety” in Yaakov would override the overwhelming positive feeling?

Role Call: “Eir…Onan…”

After Hashem essentially reassured Yaakov that everything would work out for the best, Yaakov and his family would make their way down to Egypt. At this point, the Torah gives a list and count of every family member who went down. For some odd reason though, there are a couple of people whose names make it to the list who were not among those who actually descended Egypt. On the list, the Torah mentions Yehudah’s sons, Eir and Onan. For anyone who may have missed it or have simply forgotten that the two of them died in Cana’an, two Sidros ago, because of the sins they committed amidst their respective marriages with Tamar3, the Torah mentions their deaths here so no one would make the mistake of thinking that they actually joined the family on their way down to Egypt.

Now, obviously, the Torah doesn’t actually assume that people forgot about what happened to Eir and Onan, and certainly, the Torah wasn’t attempting to tailor the narrative for those who are just tuning in now. With that said, why did the Torah include their names in this passage? Why did the Torah inform us here about the late Eir and Onan? We know that they existed and died. And so, if Eir and Onan did not go down to Egypt, their names belong no where near this counting.4

“And he appeared to him”5

Finally, when Yaakov and the rest of the family had made it to Egypt and were residing in the land of Goshen, the Torah describes the fateful reunion between Yaakov and Yosef. The Torah tells us that Yosef traveled towards his father and Goshen, and then, “Vayeira Eilav”-“And he appeared to him.”5 The question is why the Torah uses this vague expression to describe the encounter. The Torah could’ve easily said “Vayar Oso”-“And he saw him”—that Yaakov saw Yosef, or, so long as Yosef was the subject of the sentence, the Torah could have said “Vayigash Eilav”-“And he approached him” (similar to the opening of our Parsha6). The point is that there are other, more common ways with which the Torah could have expressed this interaction between Yosef and Yaakov. Why did the Torah ultimately go with the term “Vayeira Eilav”-“And he appeared to him”?

What is also strange is that Rashi felt compelled to expound on these words and explain what we might have understood as the Pashut P’shat (simple understanding), that it was Yosef who appeared before Yaakov (and not the reverse), as the Torah itself used vague pronouns; “and he appeared to him.” Perhaps, since the Pasuk does not openly reveal who was appearing to whom and one might have possibly mistaken the Pasuk to mean that it was Yaakov who appeared to Yosef, Rashi confirms that it was indeed Yosef who appeared to Yaakov. However, did Rashi really need to come and dispel this unlikely misread? The subject of the sentence until this phrase had been Yosef, so we would have assumed that Yosef was the one “appearing” to Yaakov.

Now, while it seems rather obvious who was appearing to whom, the fact that Rashi goes out of his way to interject with this seemingly obvious point might tell us that, yes, apparently, there is something strange about the Torah’s presentation. Apparently, the Torah was being somewhat ambiguous with its blank pronouns. In other words, granted, if we are patient enough to pay attention to the verse’s sentence structure and see who the subject is, we should have come to the same conclusion which Rashi had, that it was Yosef who appeared before Yaakov. However, that the Torah limited this clause to nonspecific pronouns altogether is apparently noteworthy, at least enough for Rashi to comment. Aparently, if the Torah had either said “Vayeira Yosef Eilav”-“And Yosef appeared to him” or “Vayeira El Yaakov/Yisrael”-“And he appeared to Yaakov/Yisrael,” Rashi would likely not have commented.

And again, we could argue that it really would have made little sense to mention Yosef and Yaakov by name in this clause, considering that we know who the subject in the verse and who the object is. But, if that’s true, what is so noteworthy about our verse that Rashi decided to clarify that Yosef was appearing before Yaakov?

To review and rephrase this more complicated, twofold question and catch-22 in our narrative: (1) Why didn’t the Torah specify who appeared to whom? (2) If the answer is that it was obvious that Yosef appeared to Yaakov, why would Rashi have felt the need to clarify that? That Rashi had to comment seems to imply that it wasn’t obvious, and if it wasn’t obvious, our first question is reinstated; why did the Torah specify who appeared to whom?

What to Fear

Regarding the first issue we raised, the question was how a sudden worry would overcome Yaakov in midst of his great excitement and joy about returning to his son. To answer this question, one might need some insight as to what the possible concerns about going down to Egypt were altogether, as offered by the great commentators. Indeed, Rashi informs us that Yaakov was distressed since his descent would require his leaving Eretz Yisrael.7

Zohar expounds more specifically that Yaakov was afraid that his progeny would succumb to the evil and impure ways of the Egyptians, assimilating with them, and that Hashem’s Shechinah or Divine Presence would no longer remain with them. He was concerned that his children would fall and end up beyond help and hope for redemption.

Not only are such concerns a fair reason for Yaakov’s excitement to be curbed, but we can readily understand how such concerns would have specifically compromised Yaakov’s joy about the tidings of Yosef’s survival. Perhaps, Yaakov began to contemplate the spiritual challenges which Yosef must’ve endured in Egypt. Yosef had not only joined the Egyptian society, but, Yaakov had just heard that Yosef even won himself a political position. Yaakov must’ve been genuinely concerned for Yosef’s spiritual welfare. He must have been in wonderment over the possibility that Yosef was not only physically alive but was, perhaps, somehow still spiritually intact.8

Thus, although Yosef “made it” and thrived in the Galus, perhaps Yaakov realized that it was not at all a simple task, and Yaakov could therefore not be sure that the rest of the family would rise to the occasion in the same situation. How could Yaakov expect the rest of his children to survive there? Hashem therefore assured Yaakov that He would be descending with them. As long as they could internalize that G-d is always there with him, they could succeed spiritually.9

“When the Saints Go Marching In”

Turning over to the second difficulty, we wondered why the Torah mentions Eir and Onan’s names among the list of people who joined Yaakov on his way down to Egypt, when they weren’t there. The Torah itself essentially informs us that they did not descend to Egypt, reminding us that Eir and Onan were dead. But, why was that necessary?

However, the idea which the Torah might be stressing is that yes, Eir and Onan were not there, but they should have been there. Why weren’t they there? They died a while ago as a result of their sins. The Torah emphasizes not only that they were not counted, but they were counted out. They checked themselves out by not internalizing what was spiritually important and going with the flow of their instincts. The Torah wants us to know that there was always and still is an ampty space for them on the roster! Indeed, it is a real shame when one’s name is on the V.I.P. list for an exclusive event, but for some reason, he didn’t make it to the party. When the saints go marching in, who doesn’t want to be in the number? Yes, there were spaces open for Eir and Onan in the lineage of the B’nei Yisrael, but they had to ruin it and leave an eternal gap by their spots. How could they soil such an opportunity?

The Torah depicts that the nature of their wrongdoing made them “Ra B’Einei Hashem”-“evil in the eyes of Hashem”10—evil in G-d’s eyes, but obviously, not in their own eyes. If only Hashem’s view of things would have been an important factor to them—if only they had acknowledged that G-d was present among them, maybe they could have overcome the evil.

Contrast them from Yosef who, when confronted by the opportunity to sin, told his master’s wife straightout that such an act would be an affront to G-d.11 Indeed, Chazal tell us that Yosef was on the verge of losing his tribal gemstone on the Choshen—the Kohanic breastplate—which would have left an eternal gap where his name would have belonged, but Yosef overcame his desires and cemented his spiritual legacy, earning his spot in the family lineage!12

Unlike Yosef, Eir and Onan did not “make it” when the going got tough. This dangerous reality of spiritual failure is exactly what had Yaakov concerned about descending to Egypt.

“Vayeira”—Yosef’s Magic Act

Finally, we return to the final question regarding the Torah’s presentation of Yosef’s “appearance” before Yaakov. We were wondering firstly about the peculiar term “Vayeira”-“And he appeared,” why the Torah specifically used this word to describe Yosef’s encounter with Yaakov.

Secondly, we were wondering about the ambiguous pronouns. The Torah doesn’t say who appeared to whom—though it may have been obvious. Yet, Rashi felt it necessary tell us the obvious, that it was Yosef who was appearing before Yaakov.

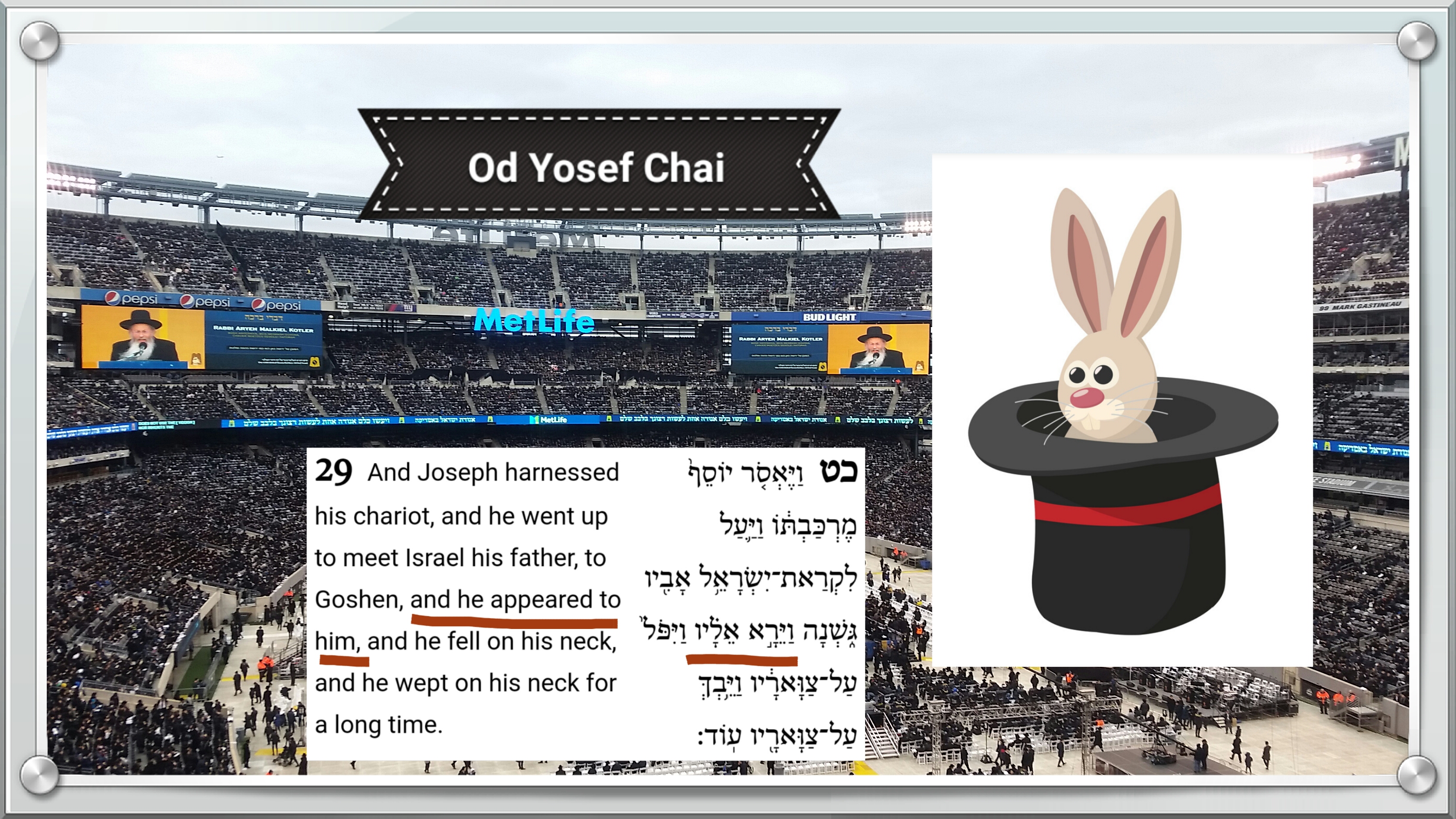

Perhaps, we can suggest that the message behind the term “Vayeira” simply serves to emphasize the perceived change in reality, that Yosef, who to Yaakov’s knowledge, had been gone, completely lost and hidden, was in some sense, “re-appearing” out of nowhere, like some kind of apparition from the afterlife. Of course, Yosef had never vanished from the face of the earth, but he was absent from Yaakov’s “world.” Indeed, Yaakov was also sort of “away” from Yosef, but Yaakov was not taken away from Yosef, as Yosef was taken away from Yaakov. Thus, the expression of “appearing” most suitably fits Yosef’s encounter with Yaakov. Like a rabbit from a magician’s hat or a quarter from your ear, Yosef “appeared” before his father.

The above approach would certainly answer the question to a degree. Despite that, it is still strange for the Torah to have emphasized this detail, moreover, to use this expression even in this context. That is because, as it happens, the term “Vayeira” is rarely used in reference to people. In reference to the Mitzvah of Aliyah L’Regel13, the seasonal pilgrimage to Israel, yes, we are commanded to appear before Hashem, but even then, the word for “appearing” is written, “Yeira’eh,” in the Nif’al (receptive) form, which more accurately means “to be seen.” In fact, this expression too would have made perfect sense in Yosef’s context, that for the first time in years, Yosef was being seen by his father. However, the active form, “Vayeira,” to literally “appear,” as if almost out of thin air, is not something that people do.

In fact, the only other times the word “Vayeira” had been used until now, were in reference to G-d Himself. The word “Vayeira” was used in Lech Lecha when Hashem appeared to Avraham and promised him that He’d give him the land of Cana’an.14 R’ Shimshon Raphael Hirsch explains there that Hashem appeared to Avraham in some tangible fashion so that although He is not actually physical, His spiritual Presence was tangibly perceivable.

The term “Vayeira” would be appear again (pardon the pun) in Lech Lecha when Hashem commanded Avraham to give himself a Bris Milah.15 The subsequent Parsha—Parshas Vayeira—would open up with the same terminology when Hashem visited Avraham following his Bris Milah.16 This term would also be used in reference to Hashem a few more times during the lives of Yitzchak and Yaakov as well.17

The point is that the term “Vayeira” is generally used when describing the tangible experience of divine, spiritual presence.

If the above is correct, perhaps that would help explain why it was somewhat important for Rashi to fill us in on exactly who, according to the simple P’shat, was appearing before whom. It is an odd word to use between two people.

Now, although, according to the simple read, that is what was happening, perhaps there is an additional layer or meaning in our verse which incorporates the true nature of this word, “Vayeira.” This other, fascinating read into our verse might even reveal a more impressive magic act of Yosef in our story.

The term “Vayeira,” as we’ve seen, represents the surreal, supernatural experience made perceivable to the human eye. Perhaps then, the same term in our context is denoting some a perceived spark of “Divine Presence”—an appearance of Hashem that was being revealed before Yaakov at that moment.

Thus, it may be that when the Torah says that Yosef “appeared,” the Torah hints that Hashem was actually revealing, to Yaakov, His own Presence in Yosef’s whole ordeal and his evident success. What now appeared tangibly to Yaakov that was not yet one hundred percent apparent before was G-d’s Presence manifest within Yosef which made him capable of overcoming all spiritual travails. Yosef’s personal attachment to the Divine Presence which led to his successes is a truly magical testament to the potential for Yaakov’s progeny to not only survive, but to thrive in Galus. Through this appearance, Yaakov Avinu perhaps could derive the confidence that although the Galus was going to be difficult and although many may fail—like Eir and Onan and like the four fifths of the B’nei Yisrael that would eventually sink in spiritual impurity18, the spirit of Yisrael would not be doomed to failure, as Hashem would always be with them. Yaakov perceived that there was hope for Yosef and that his children would likewise be capable of overcoming the Galus.19

In the end, like Yaakov Avinu, one can rest assured that Hashem’s Presence and the potential for spiritual triumph are available, everywhere and always, and all one has to do is realize it and put in the effort to tap into that spiritual energy and one may then succeed in the darkness of Galus.

May we all be Zocheh to not only survive our Galus, but to thrive in all areas despite the Galus, to have and maintain the appearance of Hashem’s Divine spark with us always, and Hashem should ultimately appear to us with the fullest Geulah from our Galus in the days of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos! Mazel Tov to Klal Yisrael on the 13th Siyum HaShas!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bereishis 46:2-4

- 45:27-28

- 38:7-10

- There are a couple of similar passages later in the Torah, for example, in Parshas Pinchas [See Bamidbar 26:9 and 26:19], where the Torah presents a census which conspicuously inserts names of the deceased with reminders of why they were not present. There, the Torah mentions Eir and Onan, yet again, and their deaths in Cana’an. Similarly, the Torah mentions Dasan, Aviram and Korach and reminds us that they were swallowed up by the earth as a result of their rebellion against Moshe and Aharon previously in Parshas Korach [Bamidbar 16:31-33]. The above question would be equally relevant in other such passages as well.

- Bereishis 46:29

- 44:18

- Citing Pirkei D’Rebbi Eliezer 39

- Indeed, Rashi to 45:27 [citing Bereishis Rabbah 94:3, 95:3 and Tanchuma 11] famously explains that when Yaakov heard Yosef’s words saw Yosef’s Agalos or wagons, that Yaakov understood that Yosef was intended a “coded” reference to the Parsha of “Eglah Arufah” (Lit., “Decapitated calf,” a law topic discussed in Parshas Shoftim [Devarim 21:1-9]), as the Hebrew word “Eigel” (calf) is similar to the word “Agalah” (wagon). This signal testified that Yosef had kept all of Yaakov’s teachings and successfully endured the spiritual challenges which Egypt posed him.

- In fact, the idea that Hashem’s Presence allows potential for spiritual success in exile is specifically evidenced by the fact that the Torah informs us that Yosef was successful considering that Hashem was there with him [See 39:2 and 39:21].

- Bereishis 38:7

- 39:9

- Sotah 36B

- Shemos 23:15-17, 34:23-24, and Devarim 16:16

- Bereishis 12:7

- 17:1

- 18:1

- 26:2, 24, and 35:9

- See Rashi to Shemos 13:18 citing Mechilta and Tanchuma, Beshalach 1.

- The “appearance” which symbolizes Yosef’s spiritual success may also explain what Hashem meant when He told Yaakov that Yosef would “place his hand over his (Yaakov’s) eyes” [Bereishis 46:4].

Rashi [to 46:29] explains that when Yaakov saw Yosef, while Yosef was crying, Yaakov was not crying because he was reciting Krias Shema—the pledge of recognition of G-d’s Presence and Oneness in the world. Yaakov’s recitation of Krias Shema may have been motivated by his recognition of Hashem’s Presence in Yosef’s life. According to tradition, based on the Minhag of Rebbi Yehudah HaNasi, one covers his eyes when reciting Krias Shema [Brachos 13B] (in order to shut out the world and can try to perceive G-d’s unity and Presence [R’ Avraham Schorr in his Sefer, HaLekach HaLibuv on Chanukah]).

Thus, perhaps for Yaakov Avinu, the sight of the vibrant Divine spark in Yosef, served the role of Yosef “placing his hands over Yaakov’s eyes,” so to speak, for him to cover his eyes, perceive Hashem’s Presence, enabling him to intently proclaim Krias Shema.