| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -Zalman Michoel Ben Golda Mirel -Ariela Golda Bas Amira Tova -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

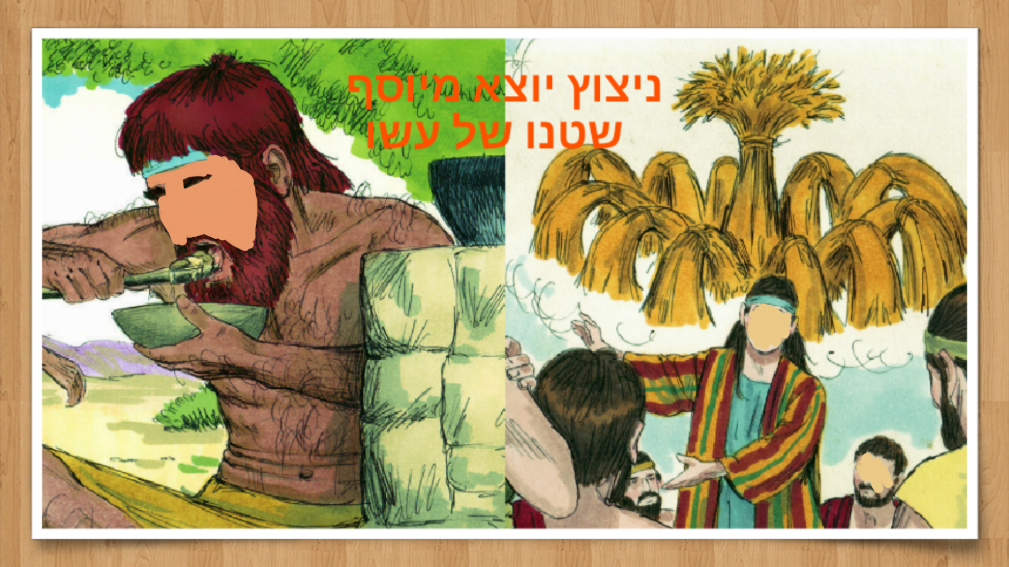

● What made Yosef the ultimate firearm against Eisav? Why did Yosef HaTzaddik instigate his brothers? ●

● וַיֵּשֶׁב ●

“A Spark from Yosef, Eisav’s Greatest Satan”

By way of introduction to the major accounts of Parshas Vayeishev, Rashi1 records a couple of profound teachings differentiating the progeny of Yaakov Avinu, who are discussed in this Sidrah, from that of Eisav, who were enumerated at the end of Parshas Vayishlach.

He points out firstly2 that the Torah chose to present the lineage of Eisav in a concise manner because they’re just really not that important, at least not enough to warrant a thorough narrative of their lives. By contrast, the chronology of Yaakov is greatly esteemed before Hashem just as Avraham’s and Noach’s were. Accordingly, they were all distinguished from the bland list of names preceding them, in that their lives and stories are broken down into great length and detail. Rashi compares the apparent dichotomy to the process of sifting jewels from sand and pebbles, Eisav being the pebbles, Yaakov being the jewels.

A Spark from Yosef

However, in later editions of Rashi is recorded an alternative teaching; a Mashal or parable of a flax dealer and a blacksmith.3 The flax dealer comes strolling by with his camels laden with bundles of flax. An awestruck blacksmith watching from the sidelines wonders, “Where is all of this flax going to be stored?” A wise man enters the scene and simply informs him, “You know, just one spark that goes out from your bellows burns up all of it.”

Likewise, Rashi points out, Yaakov saw the numerous chiefs of Eisav that the Torah mentioned and wondered, “Who can conquer all of them?” However, the Torah simply responds, “Eileh Toldos Yaakov, Yosef…”-“These are the progeny of Yaakov; Yosef…”4—that a single spark will emerge from his offspring, Yosef and consume Eisav’s entire household.

What is the source for this tradition? Rashi quotes a Pasuk from Ovadiah, actually the Haftarah for Parshas Vayishlach, where the Navi states, “V’Hayah Veis Yaakov Eish U’Veis Yosef Lehavah U’Veish Eisav L’Kash…”-“And the house of Yaakov shall be fire and the house of Yosef a flame, and the house of Eisav as straw…”5

Birth of the Anti-Eisav

The above is not the only instance in which Rashi cites this Pasuk from Ovadiah. Back in Parshas Vayeitzei as well, after Rochel has given birth to Yosef and Yaakov would prepare to take leave from the home of Lavan, Rashi writes there that it was specifically because Yosef entered the world, Yaakov felt prepared to return to Eisav as the “Setano Shel Eisav,” the adversary of Eisav, was born.6

And how would With that, Rashi brings this very Pasuk from Ovadiah as support.

A Fire, a Flame and Straw

What we’ve gathered thus far is that Yaakov’s household is represented by a fire while Yosef’s is represented by a flame, and that of Eisav is symbolized by straw.

- Fire vs. Flame

So, the first question is: What exactly is the difference between Yaakov, being the fire, and his son Yosef being the flame? Clearly, a fire and a flame are similar, certainly connected in some regard, so what does the Navi mean when it presents Yaakov specifically as the “Eish” and Yosef as “Lehavah”?

- Why Yosef?

Also, considering the analogy in the Midrash cited by Rashi as well as Rashi’s his consistent referecning of the verse from Ovadiah, it would seem that Yosef is somehow the key to Yaakov’s triumph over his wicked brother and rival Eisav. The question is, then is: How so? What makes Yosef the secret weapon against Eisav? Is it because Yosef was righteous? What about Yaakov himself? Was not the Bechirta She’b’Avos, the Chosen of the Forefathers, righteous? Moreover, Yaakov had eleven other sons who were all serving as the Tzaddikim of the generation. So, what made Yosef different? Was it because Yosef happened to be Yaakov’s “favorite” or “most beloved” son and firstborn of Rochel, his most beloved wife?

Indeed, Rashi uses these reasons among others to explain why Yosef is the main subject of the narrative and considered to be the primary progeny of Yaakov as the Torah itself implies; “Eileh Toldos Yaakov, Yosef Ben Sheva Esrei Shannah…”-“These are the progeny of Yaakov; Yosef was seventeen years old…”4

However does any of this really explain what makes Yosef the one who will consume Eisav?

Furthermore, what connection or seeming relevance do Yosef and Eisav have to one another, other than the fact that they are uncle and nephew? They seem to never really cross paths or leave any significant marks on one another in their lifetimes from what the Torah tells us. So, what does this Pasuk really mean and how really is it that Yosef is the flame that will burn down Eisav?

Evil Reports, Righteous Man?

In understanding the essence of Yosef, his first major showing in history would be the most promising first place to look. Indeed, his life story mainly begins here in Vayeishev. Apparently, he is the offspring of Yaakov, and the Torah tells us that he is a Na’ar, a lad, among the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah, his half-brothers from Yaakov’s handmaid wives.

Rashi explains that Yosef was friendly with the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah as opposed to his other half-brothers, the B’nei Leah who would demean them.7, 8

But, that’s not all. The Pasuk further testifies that Yosef would bring back “Dibasam Ra’ah”-“evil reports” about his brothers to Yaakov. Regarding these reports, Rashi points out three main sins which he accused them of, (1) eating Eiver Min HaChai, limbs from living animals, (2) demeaning the sons of the handmaid wives by calling slaves, and (3) being suspects of having illicit relationships.9, 10

Astonishingly though, Chazal tell us, two out of these three accusations were actually innacurately reported.9

Regarding the sin of Eiver Min HaChai, apparently, the animal was actually no longer living, but its body was moving so it appeared to be alive. As far as the suspicion of forbidden relationships, the brothers merely had arranged business deals with them; nothing that sketchy. Apparently though, the brothers did regard the sons of the handmaids as slaves.

The question is what Yosef is doing sending evil reports about his brothers. What in the world was his agenda? Was he right? Apparently, his accusations against his brothers weren’t entirely correct and Rashi even points out that because of his “slander,” for each report he made against them, he suffers Midah K’negged Midah, measure for measure, later in the Sidrah, even the report which was accurate!9, 11

As for why Yosef’s conduct would be punishable on every account, we can suggest simply that Yosef’s problem was not merely improper judgment. His problem was that within his improper judgment, he apparently drew an overall, inappropriate conclusion about his brothers. Indeed, in the same entry, Rashi comments that Yosef would report any negative matter about his brothers that he had seen, demonstrating his overall negative assessment of his brothers.12

So, again, what was Yosef trying to accomplish? Was he seriously nitpicking and tattle-tailing on his brothers to get them into trouble like some attention seeking father’s boy? At first glance, he was merely instigating fights, almost baselessly. And what is strange is that it seems that he’s not profiting anyone!

Ironically, crime which gets the most attention in our story is the brothers’ sale of Yosef which comes about as a result of their hatred and envy of him. And while certainly, their sin itself was unjustifiable, looking at everything from square one, Yosef appears to be the only real troublemaker in the text. Yosef not only falsely accuses them and remains the favorite, but he has the gall to announce his dreams about their wheat bundles bowing to his wheat bundle, implying that he would somehow rule over them. What is he thinking? Did he have some sort of death wish? Why was he starting up?

The kicker in all of this is, as was mentioned, that Yosef seemingly had nothing to gain by reporting against his brothers. If Yosef wasn’t particularly loved by his father, maybe all the above would easier to understand. One could argue that since he really needed the attention or affection, these reports against his brothers would get him higher on the family totem pole. But, Yosef was the kingof the hill and did not need to defend his title. He was loved, presumably the most! He didn’t need to win anything more from his father. The Torah testifies that Yosef was loved from all of his brothers, not because he had the dirt on his brothers, but “Ki Ben Zekunim Hu”-“because he was the son of his old age.”13 That would not change if he started reporting things against his brothers. His father made him a special, fine linen tunic which demonstrated to all the special relationship Yaakov had with Yosef. The unparalleled regard Yaakov had for Yosef was obvious to his brothers, and Yosef had to know that. Everyone knew that he was number one in Yaakov’s eyes. So, what more, then, did he need? Why did he start up with them?

For all of these reasons, Yosef’s actions in this Sidrah would be puzzling enough. However, they should trouble us on an even more fundamental level. Forget what is strange about the situation itself. Consider whom we’re talking about. We’re not merely dealing with a typical seventeen year old kid. Yes, Chazal tell us that he clearly manifested youthful and perhaps immature qualities.14 But, they do not tell us that he was a brat or a sinner! And if he’s involved in textbook slander and character defamation, he has a greater problem that mere immaturity. Considering that Yosef apparently struggled with simple Dan L’Kaf Zechus15, the ideal of judging favorably, with the benefit of the doubt, it seems difficult to ascribe him those same benefits. However, throughout Chazal, he is referred to as Yosef HaTzaddik, Yosef the righteous one. The question then is how Yosef can be vindicated in any respect.

What was in it for Yosef?

One of the difficulties we’ve pointed out was that Yosef didn’t need anything extra from his father. If he minded his own business, his brothers may have never even thought of killing him or selling him away. He was on cloud nine. There was no reason to get involved with his brothers. However, perhaps this difficulty is not really a question, but a clue into Yosef’s true intentions. Granted, he was not gaining personally from “instigating” with his brothers. It was social suicide to do so. We know that “personal gain” wasn’t his goal also from the fact that, even after becoming hated by his brothers because of his actions, he would still listen to his father to visit his hostile brothers in a faraway land where no witnesses would be present to observe whatever they’d plan on doing to him. Indeed, the Torah tells us that he readily complied with Yaakov’s dangerous request; “…Hineini”-“…Behold! Here I am.”15 Indeed, if his instigating was an act of social suicide, carrying out this new task would be actual suicide, which it almost was. So, if it wasn’t for himself, what was Yosef thinking when he was reporting against his brothers? What was he doing?

The Trait of the Tzaddik – Yiras Cheit

To understand the true essence of a person, one has to observe that person in midst of his greatest trials. Presumably, for Yosef, that occurred later, after he was sold away when he was working in the home of the Egyptian chief executioner, Potifar.16 Yosef undergoes this greatest of trials when the wife of Potifar, whom we’ll call “Eishes Potifar,” spent a year attempting to seduce him. Despite the fact that he was then a lowly slave bereft of any family and seemingly nothing left to lose, he adamantly denied her. “Vayima’ein”-“And he refused”17—to give in to his desires and do anything with her. He would demonstrate seemingly superhuman strength and undeniably defeat the Yezter Hara, his Evil Inclination, in a

head-on battle.

However, R’ Chaim Shmulewitz points out in Sichos Mussar18 that the main heroism displayed by Yosef was not in his initial refusal of Eishes Potifar, and not even in the fateful moment when she gets him alone and he still holds back from sinning! Yosef’s true heroism, explains R’ Chaim, is demonstrated immediately afterwards. When Eishes Potifar tries to grab Yosef, the Torah tells us that Yosef darts out of the house and even leaves his garment in her arms, doing what ever he possibly could to get out there immediately; “…Vayanos Vayeitzei HaChutzah”-“…And he fled and he went outside.”19 Just how great was this single act of Yosef?

What Did the Sea See?

R’ Chaim Shmulevitz goes on to highlight the Midrash Tehillim which reveals the generation-spanning value of Yosef’s conduct. In a familiar verse from Halleil, Scripture declares, “HaYam Ra’ah Vayanos”-“The sea saw and fled.”20 The question is: What was it that the sea saw?

The Midrash says that when the B’nei Yisrael were leaving Egypt, the Yam Suf, or the Sea of Reeds, saw the coffin carrying the bones of Yosef and fled—or better yet, it split (pun most certainly intended). And, why specifically upon seeing the bones of Yosef did it split? Explains the Midrash, Hashem decreed that for Yosef who faught his natural inclination and ran away from sin, “Vayanos,” the sea too shall too go against its course and flee. Thus, the same word, “Vayanos,” is used. Incredible.

Now, R’ Chaim Shmulewitz points out, in light of a separate Midrash that Yosef merited other rewards, one for each limb that did not give in to the enticement of the wife of Potifar.21 For example, for his body that didn’t touch sin, he later merited garments of linen when he was promoted by Pharaoh22, and similarly, for his hands which also didn’t service sin, he merited the king’s signet ring.22 The list of various adornments in the Midrash goes on.

However, Yosef’s main merit which would return to ultimately save the B’nei Yisrael generations later when they were trying to get through the Sea to escape Egypt was from his act of running away from sin. Why is running away the greatest act? Because, it is that act that truly demonstrated Yosef’s Yiras Cheit, his fear of sin. Yiras Cheit is the understanding that as long as one remains in a place where the opportunity to sin is present, that he is prone to falling victim to it, and he must get out. The Avodah of Yiras Cheit is to get out of the Makom Sakanah, dangerous situation. This was Yosef HaTzaddik—constantly being vigilant of the Yeitzer Hara at every turn, fleeing from the clutches of sin. This immense level of Yiras Cheit is how he really overcame the Yeitzer Hara.

When did Yosef Become “HaTzaddik”?

Now, regarding the question as to how Yosef could have been called “The Tzaddik” despite his evident character flaws, perhaps a simple way out is to suggest that yes, Yosef was “HaTzaddik,” however he did not earn the title until later in his life. Indeed, if there is single story which demonstrates Yosef’s true Tzidkus, it is this story of his prevailing over the trial of Eishes Potifar and how he fled from the house.

However, what if Yosef was actually a Tzaddik even earlier than that? What if, maybe—just maybe, despite his character flaws, this trait of Yiras Cheit which marked Yosef’s Tzidkus was already in the works from the beginning of Vayeishev?

The Sin of the Tzaddik – Yiras Cheit

If indeed, it is true that Yosef was this Tzaddik throughout Vayeishev, it could very well explain where Yosef was coming from when he was dealing with his brothers in he way he reacted to their questionable actions.

As was explained, Yosef was never in it for himself. He had everything going for him. He could’ve taken that and ran with it. In fact, the easy thing for him would have been to mind his own business. However, Yosef did not let the fact that “he had everything going for him” keep him from standing up for what he saw as the Ratzon Hashem. True, he wasn’t entirely accurate in his assessment of his brothers. Perhaps, as per his relationship with his brothers, his view of Ratzon Hashem was clouded. And perhaps, as the Sforno points out, Yosef did possibly lack a certain level of maturity. But, don’t be mistaken. He was no “ordinary teenager.” He was exceptionally passionate about Avodas Hashem and thus trained himself to understand that even slightest proximity to sin was a Makom Sakanah. If Yosef saw something he thought was remotely wrong or even looked wrong, he had to say something. And perhaps, he knew that his brothers would not hear it from, so if they wouldn’t hear it from him, their father would have to know. Thus, if they looked like they were eating from Eiver Min HaChain, Yosef’s Yiras Cheit alarm would go off. If they’re seemingly too close to what looks like Aveirah, Yosef could not just leave it alone.

How does any of this explain why Yosef went out of his way to relate his seemingly arrogant dreams to his brothers?

In the same vein, Yosef could’ve easily kept to himself here and would’ve saved himself much trouble for doing so. But, perhaps, Yosef felt that he needed to stick up for the demeaned sons of the handmaidens. Perhaps it was with this exact mindset that Yosef related the dreams to his brothers. It was his way of implicitly pointing out the serious misdeed they were committing towards the B’nei Bilhah and B’nei Zilpah. “Do you ever think about what your half-brothers are going through? Imagine, your eleven wheat bundles bowing down to my wheat bundle? Sounds demeaning, doesn’t it? Yet, you want to treat them like servants? Imagine being in their place. You are not servants now, but imagine what that would be like!” Of course, Yosef doesn’t ever actually say these words, which was probably a good decision. Nonetheless, he could not just the leave injustice alone. He needed to say something.

What is crucial to note here is that we’re clearly not dealing with someone who merely judges others without looking at himself. Yosef was no hypocrite. When he was forced to do the time later in life—when he was undergoing the great trial against the Yeitzer Hara, he exhibited the same passionate flare against sin which he would expect of any man! Thus, he argued with Eishes Potifar, “…V’Eich E’eseh HaRa’ah HaGedolah HaZos V’Chatasi L’Eilokim?!”-“…and [so] how can I do this great evil and have sinned against G-d?!”23—“How could I—anyone do such a thing?!”

Unlike most people who judge others (which is most people), Yosef would never judge himself any more strictly than he would another! Was he wrong in certain contexts? Yes, he certainly was! But, understand where his sin came from. It was the sin of a Tzaddik! The great mistake of Yosef HaTzaddik resulted from the fact that he constantly vigilant in his battle against the Yeitzer Hara and advocated that all ignite such a counter-flame against the heat of desire and sin.

A Flame to Yaakov’s Fire

All of the above may also explain what it means that Yosef was the flame and that Yaakov is the fire. The flame is the visible part of the fire—the fire actualized. Yaakov’s ongoing battle against Eisav was always representative of the warring forces of good and evil, serving G-d versus one’s temptations, living for the World to Come or wasting everything in This World. Thus, with his passion for Yiras Cheit, Yosef HaTzaddik represents the force that brings out Yaakov’s fire; he is Yaakov’s vitality and essence actualized.

Yosef HaTzaddik vs. Eisav HaRasha

With all of the above, we can now explain how it is that Yosef is the flame that will consume the straw house of Eisav. If we consider the contrasts between the ways they each lived their lives, Yosef is the unmistakable antithesis of Eisav.

- Living for Now?

When Eisav wanted to give up his future, the birthright, and ultimately give in to the forces of sin when felt tempted, his argumed as follows: “…Hinei Anochi Holeich LaMus V’Lamah Zeh Li Bechorah?”-“…Behold, I am going [destined] to die, [so] what [worth] is this birthright to me?”24

Yosef, on the other hand, when he has been ejected from the family, losing hope, having every reason to chuck all of the teachings from his father and give in, still has the image of Yaakov guiding him so that he can’t bring himself to sin.25 He is greatly concerned about the significance of every act he does on this world and he truly watches his every move through the spiritual microscope.

Ironically, both Yosef and Eisav look to the future when making their decisions. However, Eisav doesn’t see passed the day of his death and decides to live for right now. Yosef, on the other hand, realizes that his actions will have consequences long after he is gone, and as such, Yosef chooses to live now for the future.

- The Sibling Rivalry

Not only did Yosef overcome his inclination against all odds while Eisav readily gave in to sin. But, perhaps manifesting the same dominion over his passion, while Eisav seeks vengeance against his brother for the longest time, Yosef would not only be compassionate towards his brothers, but he would remain greatly concerned for his brothers, providing for their needs when he was in the perfect position to seek vengeance.26

- Their Once in a Lifetime Meeting

Earlier, it was mentioned that Yosef and Eisav never seemed to be involved in each other’s lives. However, there was one scene where they actually do, in a sense, meet. And based on what we know now, that single moment when they did meet speaks volumes.

Yosef’s one encounter with Eisav occurred back in Vayishlach, when Yaakov’s family had arrived from Charan to confront Eisav and his entourage. And what was Yosef doing in that scene?

The Torah tells us, “Vatigash Gam Leah Viladeha Vayishtachavu V’Achar Nigash Yosef V’Rochel Vayishtachavu”-“Leah and her children also approached and they bowed, and finally Yosef and Rochel approached and they bowed.”27

Yosef is walking before his mother. Why exactly is he positioned this way? Rashi points out that Yosef reasoned, “My mother is beautiful; lest that wicked man hang his eyes on her, I will stand in front of her and prevent him from gazing upon her.”28

What is Yosef’s concern? The heat of passion! He’s foreseeing the plot of the Yezter Hara and is taking preventative measures to stop it in its track. Indeed, in this very scene, we see Yosef realizing the power of the temptations of this world and to avoid them. Thus, Yosef combats Eisav.

Good vs. Evil?

Even after seeing all of the above, we could have simply passed off the dichotomy between Yosef and Eisav as a mere difference between good and evil, the Tzaddik versus the Rasha. One fought the Yeitzer Hara and one gave into it. But, if that is the case, we really didn’t need such an elaborate analysis, did we? There is something missing here, because why would we need Yosef to rise as the antithesis to Eisav? Did this differentiation between good and evil not exist before Yosef was born? As important as the war between good and evil is, isn’t the idea itself kind of obvious and elementary?

Indeed, if it was just about good and evil, Tzaddik versus Rasha, it would be kind of elementary. The contrast between Yosef and Eisav would be unfinished, and yes, we would be missing something crucial. That is because the connection and stark contrast between Yosef and Eisav reaches so much deeper, into their common spiritual DNA.

Where are we going with this?

Gevurah vs. Pesoles of Gevurah

Yosef and Eisav have some other key qualities in common for us to consider. Both of them were their father’s most “loved” son. Both were regarded as the firstborn by their father, though their “firstborn” status would be disputed. Both were particularly gifted by standards of the material world as Yosef was known for being physically good looking29 and Eisav was street smart and a successful breadwinner.30

But, more fundamentally, Yosef and Eisav were both shared

the same exact Midah, or attribute of Gevurah, translated loosely as “might” or “strength.” However, while Yosef manifested Gevurah in its traditional sense, the masters of Kabbalah teach that Eisav ultimately embodied what they refer to as the Pesoles of Gevurah, or the waste and dregs of the trait of Gevurah.

So, what exactly is traditional Gevurah versus the Pesoles of Gevurah? Simply put, Gevurah is the trait which was originally designed to be utilized to fight off the Yeitzer Hara, the obvious life mission of Yosef. Thus, Chazal teach us, “Eizehu Gibor? HaKoveish Es Yitzro”-“Which one is powerful? He who conquers his inclination.”31 However, the Pesoles of Gevurah is the corrupted version of Gevurah, Gevurah gone haywire. Although Eisav’s essence properly actualized would have meant utilizing his Gevurah to fend off his Evil Inclination, he used his Gevurah specifically for his own material gain, in pursuit of his Evil Inclination. Indeed, both Yosef and Eisav were Giborim, or warriors. However, they were fighting very different wars.

And here is where the contrast between Yosef and Eisav becomes so vital. Perhaps contrary to popular misconception, Yosef was not born a Tzaddik and Eisav was not born a Rasha. No one is. Yes, everyone is born with a Yezter Hara and everyone is born with natural traits and tendencies. As it happens though, Yosef and Eisav were born with the same personality traits. However, they took those same traits on different paths. That was made the crucial difference.

The Satan of Eisav

With this information, we can understand the other nickname Chazal ascribe to Yosef which we mentioned earlier in passing. In one of the Midrashim we cited at the beginning of this discussion, Yosef was described as the “Setano Shel Eisav,” literally, the Satan of Eisav. Now, that’s a funny title for a Tzaddik. We normally think of the Satan as either a devil with a pitchfork or a grim reaper. What exactly does it mean that Yosef was the Satan of Eisav?

The actual term Satan has very specific connotations, referring to an adversary and an obstacle. Indeed, Yosef, as the antithesis of Eisav, served this purpose.

But beyond that, the term Satan also means an accuser. And considering everything we’ve said, there is no greater accuser against Eisav HaRasha than Yosef HaTzaddik! They had the same traits and very similar life experiences. They both had Gevurah—the potential to stand up against the Yeitzer Hara. But, while Yosef had every excuse at his disposal to simply give in to the Yeitzer Hara and yet, still displayed that Gevurah and Yiras Cheit, Eisav dropped the ball and succumbed to his Yeitzer Hara. And until Yosef entered the scene, perhaps one could have argued that Eisav just didn’t have the means to succeed. Perhaps, Eisav’s luxuries in the material world and the Gevurah to get him whatever he wanted was a test to great to bear. However, Chazal, hitting the nail on the head, teach us that “Yosef M’Chayiv Es HaResha’im”-“Yosef obligates the wicked.”32 When Eisav is judged in the Heavenly tribunal, there will be no excuses. His greatest accuser, Yosef will be there and condemn the Rasha.

Bonus: The Kesones Passim – “Who Wore it Better?”

Just to add some icing on the cake, there is yet another Midrash33 which teaches that the Kesones Passim or the fine linen tunic which Yaakov made for Yosef34 actually came from the Bigadim Chamudim, the special garments which Yaakov wore when he impersonated Eisav and seized the blessings from their father Yitzchak Avinu.35

In an earlier discussion36, we saw a Midrash which suggested that Eisav won these garments in battle from Nimrod who ultimately obtained them from Adam HaRishon.37 In that discussion, we suggested, based on the enlightening teaching of the Or Gedaliyahu, that these garments represented the mission Eisav inherited from Adam, to redeem the Sin of the Tree of Knowledge by going out into the world of the Yeitzer Hara, and thriving in service of G-d. Apparently, Eisav failed that test, while Yosef passed it with [the tunic of] flying colors!

From beginning to end, Yosef is the undoubted flame of Yaakov’s fire in this crucial war against the Yeitzer Hara. Yes, it’s a difficult battle, but Yosef actually obligates all of us. With the same determination and Divine assistance, we can tap into and ignite that a single spark from Yosef which can entirely consume the force of Eisav and sin in this world.

May we all be Zocheh to exhibit the passionate flame of Yosef against the Yezter Hara, constantly distancing ourselves from Nisayon and overcoming all challenges in our paths, completely consuming the evil forces of this world, and Hashem should help us and reward us with the ultimate Geulah in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos Mevarchim Teiveis and a Freilichin Chanukah!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- To Bereishis 37:1

- Citing Tanchuma 1 and Bereishis Rabbah 39:10

- Citing Tanchuma 1 and Bereishis Rabbah 84:5

- Bereishis 37:2

- Ovadiah 1:18

- To Bereishis 30:25 citing Tanchuma Yashan 23

- Citing Tanchuma 7

- Note that not everyone agrees that there was a friendly bond between Yosef and the B’nei Bilhah and B’nei Zilpah; Ibn Ezra holds that he was a “lad” to them, meaning that they took advantage of him.

- Citing Bereishis Rabbah 84:7 and Tanchuma 7

- Note that Ramban, following the Ibn Ezra says that he would report about the sons of the handmaidens who made him their lackey.

- (1) For his report about their eating from Eiver Min HaChai, his brothers dipped his tunic in goat blood, not eating from it while it was alive; (2) for his accusation about their treating the handmaidens’ sons like slaves, Yosef was sold as a slave; (3) for suspecting them of having forbidden relationships, Yosef would become suspect of the very same thing in Potifar’s home.

- These reports seem to parallel another negative report, the “Dibah” against the land of Israel in the story of the sin of the Miraglim/Spies in Bamidbar [13:32]. There, the spies brought back a report of the land which consisted of an overall negative assessment of the land which was influenced by only a couple of actual questionable features of the land itself. They also did not exhibit benefit of the doubt and seemed to be returning the feedback with a seemingly biased agenda.

- Bereishis 37:13

- Rashi to 37:2 citing Tanchuma Yashan, Mevo ms. 3, 13 and Bereishis Rabbah 84:3

- Pirkei Avos 1:6

- Bereishis 39

- 39:8

- In his piece on Parshas Vayeishev in the entry labeled “S’chor S’chor Amrinan L’Nazira”-“‘Go around! Go around!’ We Say to the Nazir.’”

- Bereishis 39:12

- Tehillim 114:3

- Bereishis Rabbah 90:3

- Bereishis 41:24

- 39:9

- 25:32

- Rashi to 39:11 citing Sotah 36B

- Bereishis 41-50

- 33:7

- Citing Bereishis Rabbah 78:10 and Pesikta Rabbasi 12

- Bereishis 39:8

- 25:27

- Pirkei Avos 4:1

- Yoma 35B

- Midrash from the Yalkutim Teimanim Kisvei Yad and the Midrash HaBiur Neir HaSichlim, cited in Torah Shleimah commentary on the Torah.

- Bereishis 37:3

- Bereishis 27:15

- See what I wrote earlier; “A Tale of Trees and Tree-Monsters,” Yaakov’s New Challenge – Clothes From Eden, Parshas Toldos.

- Pirkei D’Rebbi Eliezer 24