| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -Zalman Michoel Ben Golda Mirel -Ariela Golda Bas Amira Tova -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

וַיִּגַּשׁ ● Vayigash

● Does this showdown between brothers seem familiar? ●

“Clash of the Brothers II”

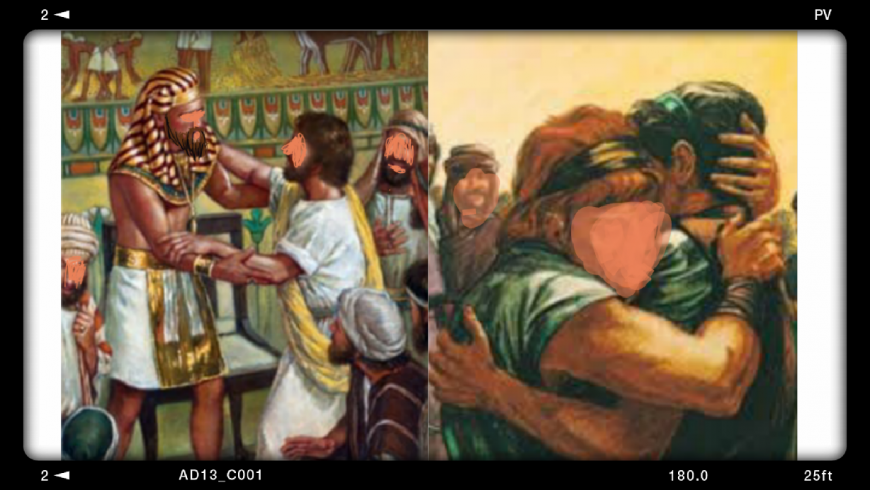

In perhaps the most emotional and climactic scene in the entire Torah, Yehudah courageously steps forward and stands face to face with his brother Yosef just moments before Yosef finally reveals his identity to his brothers. This faceoff is laden with profound meaning; we have two brothers, the pillars of Israelite kingship from whom a Moshiach is destined to emerge at the end of days. One son, Yehudah, is representing Leah Imeinu and the other, Yosef, is representing Rochel Imeinu, quite an epic showdown to say the least.

Just to review how we’ve arrived at this “main event,” we know that Yosef was sold away as a slave by his brothers. Twenty-two years later, unbeknownst to his brothers, he had been elevated to the position of viceroy over all of Egypt. Then, during the famine, when his brothers arrived to buy some food, when they didn’t recognize Yosef, Yosef, the “undercover” viceroy, had put on a harsh façade, imprisoned his brother Shim’on as his hostage, demanding that the youngest brother Binyamin be brought down if the rest of the family wanted to redeem their brother and collect any more means of sustenance. Now, after pretending to accuse Binyamin of stealing from the kingdom, Yosef has decreed that Binyamin remain in Egypt as a slave. Yosef is now waiting for a response. The ball is in his brothers’ court, and here we are.

So, what happens? The Torah tells us, “Vayigash Eilav Yehudah…”-“And Yehudah approached him…”1 Yehudah made the fateful move and respectfully, but quite passionately opened up his argument to Yosef, explaining, not only how uniquely important Binyamin is to their father Yaakov, but how he personally assumed responsibility for him.2 Somewhere in this encounter Yosef would capitulate and break the charade after which point the family would slowly fall back into place with an emotional eruption of tears and comforting words.3 But, before that point, the tension was certainly building and hearts were racing. Yehudah was ready to do anything and everything—from becoming a slave to being a mass murderer—to protect Binyamin.

The story is riveting every single time, but does any of it strike you as being familiar?

“Vayivaseir Hu Levado”- “And he was left alone”

If not, consider the following. Amidst his final appeal to Yosef, after stating that Binyamin’s maternal brother is gone, Yehudah describes Binyamin saying “…Vayivaseir Hu Levado…”-“…and he [Binyamin] was left alone…”4

Now, for anyone unsure of where else this rare expression comes up, the Ba’al HaTurim points out that this phrase parallels that which was said of Yaakov Avinu back in Parshas Vayishlach just before his encounter with his rival and brother Eisav; “Vayivaseir Yaakov Levado…”-“And Yaakov was left alone…”5

The Ba’al HaTurim explains that just as Yaakov was getting ready for war with his brother, here too, when the very same expression of being alone is employed, Yehudah is getting ready to go to war with his brother. Interesting.

The parallel of this expression of “Vayivaseir…Levado” and the idea of brothers going to war with one another is certainly fascinating, but is that all there is here?

Certainly, if we were to vote on the two most climactic and emotional, brotherly confrontations in the Torah—perhaps in history itself, the academy award would go to our scene between Yehudah and Yosef and the earlier one between Yaakov and Eisav. But, beyond the drama of the two scenes, if we keep on investigating these two scenes, examining both the text and Chazal’s exegesis of both stories, one will see how apparently deeply they’re actually connected.

Preparing for Peace and for War

Back in Vayishlach, Rashi pointed out that Yaakov took three major preparatory measures for his reunion with Eisav6; (1) he prepared a Minchah or a tribute to appease him7, (2) he prepared for war by dividing his camp6, and he prayed to Hashem.8 Interestingly, in our story, the brothers prepare in a glaringly similar fashion. Yaakov tells them to bring a Minchah9, he prayedon their behalf10, and Rashi points out that Yehudah prepared to war with Yosef.11

Moreover, the Midrash Lekach Tov points out that Yehudah himself implemented all of three of these preparatory acts within his encounter with Yosef—that he tried to appease Yosef, prayed to Hashem, and was set to go to war if need be.

“Approaching”

But that’s not all. Furthermore, the expression of “Hagashah,” the root term for “approaching” or “confronting,” appears a number of times in both encounters.12

“Bowing”

In both stories, Yaakov is humbled multiple times as he either calls himself or is referred to by others as the apparent antagonist’s “servant.”13 Furthermore, in both stories the protagonists fatefully perform a series of bowings before the “enemy,” as Yaakov and his family prostrate themselves before Eisav, and Yosef’s brothers do the same before before him.14

“Crying”/“Kissing”

Also, as we’ve alluded to earlier, both narratives begin with what seems to be a war, but ends up culminating into an outbreak of love—falling on necks, kissing and subsequent crying.15

A Mysterious “Ish”

A final and interesting connection between the stories is that both include an intense, emotional and metaphysical struggle with an unidentified “Ish”-“man.” On the one hand, Yaakov wrestled the mysterious “Ish”5 (whom, according to Chazal, was the guardian angel of Eisav16). And in our story, athe “masked” viceroy of our account, Yosef, is referred to more than once as the “Ish.”17

Undoubtedly, these grand showdowns have much to do with one another. But, the question is why? Why do these two stories meet? What is the real connection?

Showdown I (Vayishlach) vs. Showdown II (Vayigash)

As similar as they might appear, to truly understand the interplay between them, we have to identify the key differences between these “showdowns.” Their differences are obvious, but vital for the next step of this analysis.

- Eisav HaRasha vs. Yosef HaTzaddik

In a previous discussion, we’ve discussed at great length, the surprising similarities and the glaring differences between Yosef HaTzaddik and Eisav HaRasha.18 But, to keep things simple, what is clear is that these two individuals are ultimately diametric opposites.

Yosef was not exactly a villain hailing from the “dark side” which Eisav would ultimately identify with. His guardian angel was not the Satan as Eisav’s was. Yosef merely pretended to be the enemy.

Moreover, between Yaakov and Eisav, Yaakov was the undoubted protagonist. However, in our story, some might argue that Yosef was just as much a protagonist as his brothers were. After all, they’re all Yaakov’s progeny and are therefore all of the chosen nation. And as was mentioned, Yosef is only a “pretend” enemy.

In this light, while Yaakov was preparing for war with a begrudging brother, the “war” Yehudah was preparing for against his brother was never going to be an actual war. He apparently had no intentions of seeking vengeance against his brothers or actually enslaving Binyamin. He is a clear Tzaddik who is ultimately sustaining them and protecting them. He returned their money to them, treated them quite well and he even made the effort to keep them from being publicly embarrassed when he eventually revealed himself to them. For them at that moment, it might have looked like a “war,” but they would shortly find out that that they were being set up and that no one was ever seriously in harm’s way. It was all a show.

On the other hand, Eisav is a Rasha and likely had every intention of taking Yaakov’s life at least before their encounter. In fact, where the Pasuk writes that Eisav kissed Yaakov, there are dots written over the word “Vayishakeihu”-“and he kissed him”19 indicating either that Eisav did not kiss Yaakov wholeheartedly, or the famous opinion the opinion of R’ Shimon Bar Yochai that although in general, “Eisav Sonei Es Yaakov”-“Eisav hates Yaakov,” at this particular moment, Eisav kissed Yaakov and meant it wholeheartedly.20 Whichever meaning is intended, the idea is that there’s a general, intrinsic animosity that Eisav feels against Yaakov. Apparently though, Yosef did not harbor any hatred for his brothers—that he assures them of openly.21

So, although the stories appear similar, they’re really quite different. What, then, are we meant to learn from the apparent association we’ve identified between them? What is either encounter supposed to represent and convey in light of the other?

Two Wars

As the Ba’al HaTurim originally put it, there are two apparent “wars” presented in these two main-event, history-in-the-making showdowns. The textual and thematic details we’ve provided in each one reveal hints to the other. But if these fiery family reunions are really so different natured, the apparent relationship between the two is quite bewildering.

However, perhaps the Torah’s intention, as well as that of Chazal, is to connect the two scenes for the sake of highlighting both the crucial common denominators that they share as well as the apparent contrast between them, to depict for Klal Yisrael today, what eternal battles our nation will evidently have to face throughout life in this world. What are these “two wars”?

“Eisav Sonei Es Yaakov”

The first confrontation, between Yaakov and Eisav, might represent the war with the Satan, the eternal struggle against utter evil. This evil may be that of the Evil Inclination as well as that of the nations of the world whose persistent mission is to subjugate, persecute or wipe out the B’nei Yisrael. It causes them to stumble, leads them away from the path of Torah, and sometimes even takes their lives. In this war, we need to create distance from the enemy, because indeed, this war is symbolized by the reality of that which R’ Shim’on Bar Yochai refers to as a Halachah, a rule, that “Eisav Sonei Es Yaakov,” that Eisav eternally hates Yaakov.20 This measure—creating distance, is actually what Yaakov took in this battle. Avoiding friction and enmity, Yaakov decided to send Eisav off in another direction as he wanted nothing to do with his eternal adversary.22 How about the other “war”?

“Kal Yisrael Areivin Zeh BaZeh”

Our second confrontation may represent an entirely different dimension of struggle in this life, the perhaps more threatening and equally drastic war within family—between well-intending brothers. Unfortunately, there is also a seemingly eternal struggle, an interior war, within family. This “war” is one that truly breaks hearts because neither side necessarily intends to wrongly harm a brother, but neither side gives the other a fair chance either. Each party readily judges the other harshly, whether due to envy, pride, apparent external differences or whatever cause there is to the apparent feud and contention.

We know that Yosef was faking the hostility towards his brothers, but, what was it all for? What was this “war” really about? Yosef was looking to see what would be of the feud between Yaakov’s children, the B’nei Leah and the B’nei Rochel. Did his half-brothers who once hated him and sold him away learn from their tragic past? Would they stand up for their other half-brother Binyamin? Would there finally be closeness and love in the entire family? Indeed, When Yehudah stepped forward and claimed, “Ki Avdecha Arav Es HaNa’ar…”-“For your servant guaranteed the lad…”23 In othe words, he showed Yosef that there was hope. This other “war” is symbolized by a different Halachah, “Kal Yisrael Areivim Zeh BaZeh”-“All of [the Children of] Yisrael are guarantors with one another.”24

In the beginning, Yaakov struggles with an angel, the “man,” to eventually create the necessary distance from the enemy, Eisav. However, when the brothers are forced to struggle with Yosef, it was ultimately to strengthen the entire family bond, to help brothers see each other as brothers, and not, Chas Va’Shalom, as rivals or enemies. Similarly, we have to be aware of these “wars” in our lifetime. While, granted, there are enemies in the world because “Eisav Sonei Es Yaakov,” however, as far as Am Yisrael is concerned, we have to stick together by all means for, “Kal Yisrael Areivim Zeh BaZeh”-“All of [the Children of] Yisrael are guarantors with one another.”

May we all be Zocheh to be aware of these wars, be able to distinguish between the two, and know how to properly handle each one so that we can deflect our true enemies and stand up for our brothers, and there should be ultimate peace from all wars soon with the coming of our Geulah in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bereishis 44:18

- Ibid. 44:20-34

- Ibid. 45:1-14

- Ibid. 44:19

- Ibid. 32:25

- To 32:9 citing Tanchuma Buber, Vayishlach 6

- Bereishis 32:14

- Ibid. 32:10-13

- Ibid. 43:11

- Ibid. 43:14

- To 44:18 citing Bereishis Rabbah 93:6

- Bereishis 33:3-7, 44:18, and 45:4

- Ibid. 32:31 and 43:28

- Ibid. 33:3-7 and 43:26-28

- Ibid. 33:4 and 45:14-15

- Rashi to 32:25 citing Bereishis Rabbah 77:3 and Tanchuma 8

- E.g. Bereishis 43:11

- For more on the relationship between Yosef and Eisav, see what I wrote earlier; “A Spark from Yosef; Eisav’s Greatest Satan,” Parshas Vayeishev.

- Bereishis 33:4

- Rashi there citing Sifrei in Beha’alosecha 89

- Bereishis 45:12

- Ibid. 33:13-14

- Ibid. 44:33

- Sanhedrin 27B and Shevuos 39A