| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben Yosef A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta-MY BROTHER: MENACHEM MENDEL SHLOMO BEN CHAYA ROCHEL -HaRav Gedalia Dov Ben Perel -Yechiel Baruch HaLevi Ben Liba Gittel -Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze

|

בס”ד

מִּשְׁפָּטִים ● Yisro

● Why are the laws of the courts interrupted by the laws of an enemy’s animal? ●

“Patterns in Mishpatim: The Path of the Just”

Despite Parshas Mishpatim’s apparent detour from the narrative, the seemingly dull passages of law are actually filled with deeper wisdom and meaning than the simple reader might realize. We will shortly see that no simple law is just a simple law, and there is necessarily more beneath the surface. Hashem’s Torah apparently has a “way with words,” and indeed, if we pay attention to the words and their presentation, we can pick up on the subtleties within, find layers beneath the laws and uncover those teachings. No, there’s no narrative here, but Hashem’s passages of laws do tell their own story.

With that said, let’s take a look at another set of laws from Mishpatim, namely the laws related to the justice system. For some reason, the Torah scatters some of these laws around in a seemingly less than intuitive way. As was done in the previous discussion, we will provide some text to be referred back to.

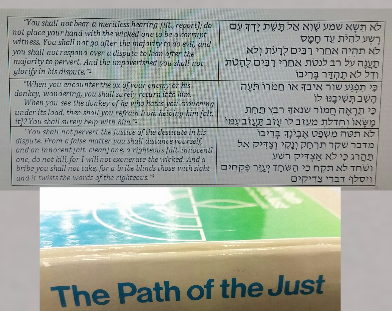

| The Justice System – Shemos 23:1-8 | |

| “You shall not bear a meritless hearing [lit., report]; do not place your hand with the wicked one to be a corrupt witness. You shall not go after the majority to do evil, and you shall not respond over a dispute to lean after the majority to pervert. And the impoverished you shall not glorify in his dispute.”1 | לֹא תִשָּׂא שֵׁמַע שָׁוְא אַל תָּשֶׁת יָדְךָ עִם רָשָׁע לִהְיֹת עֵד חָמָס לֹא תִהְיֶה אַחֲרֵי רַבִּים לְרָעֹת וְלֹא תַעֲנֶה עַל רִב לִנְטֹת אַחֲרֵי רַבִּים לְהַטֹּת וְדָל לֹא תֶהְדַּר בְּרִיבוֹ |

| “When you encounter the ox of your enemy or his donkey, wandering, you shall surely return it to him. When you see the donkey of he who hates you crouching under its load, then shall you refrain from helping him [alt. it]? You shall surely help with him.”2 |

כִּי תִפְגַּע שׁוֹר אֹיִבְךָ אוֹ חֲמֹרוֹ תֹּעֶה הָשֵׁב תְּשִׁיבֶנּוּ לוֹ כִּי תִרְאֶה חֲמוֹר שׂנַאֲךָ רֹבֵץ תַּחַת מַשָּׂאוֹ וְחָדַלְתָּ מֵעֲזֹב לוֹ עָזֹב תַּעֲזֹב עִמּוֹ |

| “You shall not pervert the justice of the destitute in his dispute. From a false matter you shall distance yourself, and an innocent [alt. clean] one, a righteous [alt. innocent] one, do not kill, for I will not exonerate the wicked. And a bribe you shall not take, for a bribe blinds those with sight and it twists the words of the righteous.”3 | לֹא תַטֶּה מִשְׁפַּט אֶבְיֹנְךָ בְּרִיבוֹ מִדְּבַר שֶׁקֶר תִּרְחָק וְנָקִי וְצַדִּיק אַל תַּהֲרֹג כִּי לֹא אַצְדִּיק רָשָׁע וְשֹׁחַד לֹא תִקָּח כִּי הַשֹּׁחַד יְעַוֵּר פִּקְחִים וִיסַלֵּף דִּבְרֵי צַדִּיקִים |

In the first verse, the Torah commands one not to accept false or meritless reports and not to follow the majority against one’s better judgement.1 And in the following verse, the Torah commands one not to in any way favor the poor in a dispute1, continuing the theme of proper judgment in the court.

But after that, the Torah interrupts the courtroom laws and veers off to a seemingly random discussion about what happens when one encounters his enemy’s animal on the road, whether the animal is lost or crouching under a burden.2

It is only after this discussion that the Torah returns to the courtroom, seemingly to repeat or elaborate on how to deal properly with the poor in court, warning one not to pervert the judgment of the destitute.3 Finally, it commands that one distance himself from falsehood, that one not accept a bribe, and that court verdicts be decided by a majority rule.3

Lack of Organization

The question is why the Torah presented these laws in this seemingly unorganized way. Why were the laws of “one’s enemy’s animal” inserted where they were in this group of court laws? And why did the Torah split up almost identical sounding laws of the poor man in court? It seems almost as though the discussion about the poor litigant was interrupted so that after the digression to the topic of one’s enemy’s animal was finished, it needed to return to the earlier discussion and regain our focus from what was an obvious distraction. So, what exactly is the basis for the strange setup in these passages?

“The Impoverished,” “Your Enemy” – Why the Labels?

Another question one might ask is why the Torah bothers to label the individuals in these circumstances. For example, the Torah commands one not to favor “the impoverished.” Did the Torah need to specify his financial status? A good judge would not and should not favor anyone. That is the Torah’s point, isn’t it? And the poor man should be understandably included in “anyone.” If that is the case, the Torah should simply have commanded a judge not to favor anyone and pervert the justice of anyone.

Moreover, if the Torah wanted one to return lost objects or animals, or to help load an animal, again, it shouldn’t have to specify one’s enemy’s animal. Just command man to return all lost animals, and to help load all people’s animals. The law is the law, and should be the same, presumably for anyone and everyone. Why, then, did the Torah paint these pictures for us, labeling the individuals in these passages?

Bringing Laws to Life

As was mentioned above, a law, in the Torah, is more than just a law. Hashem’s Torah is necessarily telling us something deeper here. There likely is a story to be told here and a point to be made. What is that point?

Hashem knows that we are human and therefore have a human way of thinking. The law may be the law, and it may be the objective law, but we humans tend to obscure matters when we’re in the situation and our own feelings and preconceived notions of fairness start to govern our actions. The Torah preempts the rationalizations and gives us, more than mere laws of correctness, but a teaching we can relate to, one that hits home and speaks to our human notions.

With that in mind, what can we glean from the fashion in which the Torah presents these teachings?

Chiasm of Justice

Before we can fully answer that question, we need to turn our attention once again to the textual presentation itself. If one looks at our seemingly counter-intuitive passage, one will indeed find yet another chiasm in the laws of Mishpatim, much like the one we identified earlier.4

In our context, the simple chiasm is arranged as follows:

A1) Correct Judgment [23:1-2]

B1) Dealing with the poor in court [23:3]

C) The enemy’s animal [23:4-5]

B2) Dealing with the poor in court [23:6]

A2) Correct Judgment [23:7-8]

The most obvious theme in the entirety of the chiasm would seem to be the idea of justice. Now, again, the Torah couldn’t just state, “be just” or “be a good person.” We’re all “good guys,” hopefully, or at least we would like to think we are, but if we’re not thinking about the specific cases we might encounter at any moment and we just act on our instincts, merely assuming we represent justice, we may not actually deliver. We may resort to our own justice system and actually pervert justice.

Therefore, here, the Torah presented us some “real-life” situations and did so in the format depicted above. What does it mean though? And why were the laws of the enemy’s animal placed in the middle? And is the second half of the chiasm just a reaffirmation of the first half? From the view of our chiasm above, it seems that the first half merely charges us, “Be just,” and the second half merely reiterates the sentiment, “Be just.” But, why would that be necessary?

Chiasm of Justice – Advanced

If one looks closer, as we saw earlier2, there’s actually a subtle difference between the two sides of this chiastic passage. The themes are the same and many of the details parallel one another, but the first half seems to present what we might refer to as “innocent” miscarriages of judgment while the second half appears more malicious. For example, while both halves condemn acquitting the guilty, the first half, in A1, merely commands one not to help the wicked, while the second half, in A2, warns one not to, in turn, harm the righteous and innocent, “…V’Naki V’Tzaddik Al Taharog…”-“…and an innocent [alt. clean] one, a righteous [alt. innocent] one, do not kill…”5

Indeed, although the simple individual might be misled into helping the wicked person, he certainly wouldn’t want to hurt the innocent. Sometimes, though, if one helps the wicked, it means harming the righteous.

Similarly, the first half commands one not follow the majority although we can understand the inclination to do so. It seems correct at times—perhaps the majority knows better than you do. Yet, the second half warns one against accepting bribery, something that is obviously rooted in greed, and certainly reeks of corruption.

Furthermore, while in the first half of the chiasm, in B1, the Torah forbids favoring the poor, we can really understand why it would be “kind” to do so. After all, he’s poor. His life is hard. Perhaps we should give him a break. With positive intent, one may be inclined to help him out. On the other hand, in the second half, in B2, the Torah commands one not to pervert the judgment of the destitute—that can mean helping him or hurting him. But, who in their right mind would want to oppress the poor man in court? One would think only a sociopath would be so malicious. Yet, the Torah makes sure to put this one down, for the sake of the “sociopath.”

Then we get to the middle variable, C. Indeed, the center of the chiasm can actually also be split into two halves as there are two laws regarding one’s enemy’s animal: (1) to return it if its lost, and (2) to help it up from under its load. Here too, we have a more “innocent” miscarriage of judgment versus a more malicious one. One can understand why I wouldn’t want to return my enemy’s animal. I don’t care to steal it—we already know that that’s not okay. But why should I have to go out of my way to return it to my enemy? We could argue that it is fair and proper to just leave it where one found it. However, for the animal under its load, again, one would have to be cruel to leave it there on the floor under the luggage, possibly in pain. Moreover, even if it is his enemy, that should not determine whether or not he is going to help another person, and the fact that he actually sees this person—enemy or not—struggling on the roadside and can choose to snub him takes another degree of brazenness than to merely ignore a wandering animal. But, at the end of the day, justice dictates that we help, in either of these circumstances equally.

Thus, the somewhat advanced chiasm looks like this:

A1) Integrity in Judgment—“Honest Mistake” [23:1-2]

B1) Favoring the poor in court—“Honest Mistake” [23:3]

C) Returning the enemy’s animal—“Honest Mistake” [23:4]

C) Loading the enemy’s animal—“Malicious Intent” [23:5]

B2) Oppressing the poor in court—“Malicious Intent” [23:6]

A2) Not Corrupting Judgment—“Malicious Intent” [23:7-8]

Considering the above, the question now is why the Torah assumes the absolute worst in man. Do we need to have special commandments to help a suffering animal, not to be corrupt against the poor, and not to kill the righteous and innocent?

Injustice is Injustice

Apparently, yes. Again, there are many truths, obvious truths, yet, when we find ourselves in just the right situations, we might only notice our own conceptions of those truths which may often be misconceptions, in other words, false. Many things seem proper, i.e. following the majority, favor the poor. We may pursue these deeds with the best of intentions. But to follow the majority without seeing the case through for oneself is not good and not just, just like bribery is not just, even if one “would never accept a bribe.” Favoring the poor in court is unjust as is being corrupt against the poor, even if one is obviously more malicious. And if we pick and choose when we’re going to uphold justice, we are being unjust, no matter what backstory one can provide for either party. We do this and we subsequently corrupt ourselves and commit larger crimes that we can only imagine a malicious sociopath would do. Helping the wicked becomes killing the innocent. Well-intended miscarriage of justice is still a miscarriage of justice which can evolve into even more malicious perversion of justice.

That may be why the Torah specifies that it may be a poor man or your worst enemy. It doesn’t matter who it is, we have to treat all justly because justice dictates that we do so! We can’t lose ourselves in the warp of falsehood and ignore suffering animals because one’s enemy is on the other end. It doesn’t matter who it is, but Hashem knows how we humans think.

In the same vein, this series is not merely a set of laws for judges in the courtroom, but a code of ethics for everyone, even the commoner on the road. Ethical judgment calls are in order for all situations, whether the question is deciding a legal verdict or helping a person on the road, friend or enemy. And one who miscarries justice in any situation, even where it seems reasonable, has nonetheless committed an injustice. And if one can bring himself to do that, perhaps he leaves himself prone to committing the unimaginable injustice.

Indeed, Shaul HaMelech suffered from one miscarriage of justice to the next in the entire second half of Sefer Shmuel Aleph because he was preoccupied with the rationalizations for his “unique circumstances.” As a result, he showed mercy on the wicked Agag, the descendant of Amaleik, and later ended up killing out the innocent city of Nov.

As we look at the entire passage, the Torah is clearly teaching that proper judgment comes from total impartiality and objectivity, seeing matters from lenses outside oneself, one’s personal feelings and preconceived biases. Truth and correctness stands independently in all cases, regardless of who the “judged party” is relative to you.

We’ve seen that mistreating the rights of our personal enemies in our own situation is just as much an injustice as is corruption in the courtroom is. Indeed, justice is not just something for the courtroom, and that is why the seeming climax of our passage pins us versus our worst enemy and instructs us to ignore our feelings and focus on justice. Thus, the Torah teaches us that justice is not something we can just assume we have. It is not as simple as intending to do the right thing. It takes serious intellectual honesty and nullification of our own feelings to deliver proper justice. We have to see ourselves as always being in a courtroom before the One and Only Judge of Truth, the only source of true Justice. When we do so, we will maintain a healthy pace of the path of the just.

May we all be Zocheh to view every situation through the lenses of true justice, follow, not our own feelings, but Hashem’s pure direction and truth, and we should judge every situation properly, walk on the path of the just, and Hashem should help us succeed on that path which should lead us towards the Geulah in the days of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos Mevarchim Adar!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Shemos 23:1-3

- 23:4-5

- 23:6-8

- See what I wrote earlier in this Sidrah; “Patterns in Mishpatim I: The Avos Nezikin.”

- Shemos 23:7