This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta

-Miriam Liba Bas Devora

-Aharon Ben Fruma

-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamah of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus.

בס״ד

בַּמִדְבַּר ~ B’Midbar

“The Central Goal”

Raise up (count) the head the entire assembly of the B’nei Yisrael...

שְׂא֗וּ אֶת־רֹאשׁ֙ כָּל־עֲדַ֣ת בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָ֖ם לְבֵ֣ית אֲבֹתָ֑ם בְּמִסְפַּ֣ר שֵׁמ֔וֹת כָּל־זָכָ֖ר לְגֻלְגְּלֹתָֽם׃

Raise up (count) the head the entire assembly of the B’nei Yisrael...

שְׂא֗וּ אֶת־רֹאשׁ֙ כָּל־עֲדַ֣ת בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָ֖ם לְבֵ֣ית אֲבֹתָ֑ם בְּמִסְפַּ֣ר שֵׁמ֔וֹת כָּל־זָכָ֖ר לְגֻלְגְּלֹתָֽם׃

Numbers.1.1-2

Numbers.2.2

A close analysis of Sefer B’Midbar’s narratives will reveal quite evidently that the Torah has, at least in this section, abandoned chronological order in its recounting of the stories.

Chazzal have noted that while the Torah indicates very clearly that the Census at beginning of B’Midbar took place in the second month of the second year of the B’nei Yisrael’s Exodus from Egypt [B’Midbar 1:1], the narrative recorded two Sidros later regarding the individuals who missed out on the Korban Pesach is explicitly said to have taken place in the first of month of that same year [See Rashi to 9:1 citing Sifrei, B’Ha’alosecha 1:18] before our Sidrah. Thus, even the Ramban who adamantly maintains that, as a rule, the Torah stays true to chronology, is forced to admit at least here that “Ein Mukdam U’Me’uchar BaTorah”-“There is not [always necessarily] a before and after in the Torah” [Pesachim 6B].

Leaving the Ramban aside, there are many commentators apply “Ein Mukdam U’Me’uchar…” more “liberally” and have noted several places in the Torah, especially in Sefer B’Midbar, where they suggest that the chronology is off, for example, the Ibn Ezra, who suggests that Korach’s rebellion, which is recorded after the narrative of the Spies, actually took place at the time of the Mishkan’s inauguration, much earlier, before Parshas B’Midbar had even taken place.

For this reason, many of the stories throughout the Torah are subject to debate as to when exactly they occurred.

So, the question is: Why? Why would the Torah have been put together in such a seemingly disorganized fashion so that certain stories should end up out of order?

The seemingly disorganized piecing of various Torah texts, which we call “Ein Mukdam U’Me’uchar BaTorah,” is challenging, but it does not at all mean that the Torah held chronology in low regard. But, what does demonstrate is that the Torah is quite selective in what it chooses to discuss and when, and that some values are more important than chronological order.

Whatever these values are, these same values would also explain why various stories and law sets are separated into different segments of the Torah based on their differing themes and styles. Indeed, Chazzal very clearly understood that the covenant was intentionally made up of Chamishah Chumshei Torah, the Five Books of the Torah. Contrary to the supposed “hypothesis” that the Torah was possibly made from differing human-written “documents” which later ended up being spliced together, Chazzal knew better that, completely on purpose, there were Chamishah Chumshei Torah, the Five Books of the Torah, or more literally “Five Fifths of the Torah,” as each book is really one fifth of a single whole. Because, indeed, that’s what it is: a single whole with a single goal.

What is that goal? And why do we need five different books to understand that goal?

The goal of the Torah is to teach the B’nei Yisrael about its relationship with Hashem and with the world around them, what Hashem expects of the B’nei Yisrael in every single facet of their collective and individual lives.

The challenge is that we humans are multi-faceted. There are many dimensions in our lives. With that in mind, Hashem separated the Torah into five stylistically different books, each with the same exact central goal in mind, but each with a particular focus on a different dimension and application of that central goal. That means that the Chumashim, the five fifths of the Torah, are all interconnected and that the center of each of them is our relationship with Hashem. That makes each division equally binding and of equally Divine authenticity. That said, the Torah was designed like a prism so that each of the Chumashim represents a different dimension of that relationship, a different perspective of the same exact goal.

With those basics established, we can begin to understand why it is not only fair, but sometimes appropriate that the Torah only presents certain laws in certain books, certain stories in others, and why sometimes, even the order of the stories has to be altered against chronology. In that light, why a certain story which might’ve happened way before the Census in the beginning of B’Midbar would end up being placed much later might be because Hashem wanted us to see that story through the perspective of B’Midbar and not through a different division of the Torah.

So, the question is: What is the division of B’Midbar about? What about our relationship with Hashem and the world around us does B’Midbar reflect?

Well, in order to answer that question, we have to get some context from the other books of the Torah.

Considering the larger Torah prism, looking through the Torah narratives, one might notice that each Sefer (perhaps with the exclusion of Devarim which contains almost no new narratives) includes the creation of some realm which represents perfect order, a utopian society, yet that realm is disturbed by one or more central sins which represents the destruction of that order and much of the society.

Bereishis is the Genesis or the Beginning of everything. It is Creation of the perfect utopian world, and it tells the story of Hashem’s interactions with man directly. And what happens in these early interactions. In short, Creation slowly unravels into destruction. Hashem made a world, and mankind, through sin and corruption, destroyed it. It began with Adam eating from a forbidden tree and ended with a generation so socially debased that the world had to be destroyed. It would take the effort of one Abrahamic family to steer the world on the way back to its former glory.

Shemos tells us about a liberated nation who reaches its spiritual peak at Har Sinai where they entered a marriage with Hashem and accepted the Torah. But much like in Bereishis, despite their near spiritual perfection, that perfect reality was disturbed by the sin of the Golden Calf. This time, the disturbance was on a national level. As close as they were, the world would not be fully restored to its former glory.

But, it’s okay, because Vayikra picks up from Shemos where a new project was completed, the Mishkan, a mini-world for Hashem’s Presence, a small world of concentrated holiness and perfection where individuals can seek out G-d and nothing could go wrong. But, of course, another sin occurs, this time from Nadav and Avihu, Kohanim who abused the holy services, and the perfect order is disturbed once again.

And so now, we reach B’Midbar, a very complicated book, perhaps the most complicated book in the entire Torah. Such a complicated book B’Midbar is, it is difficult to pin down which sin it was that ruined the project; was it the B’nei Yisrael’s complaining about EVERYTHING? Was it the Sin of the Spies? Was it Korach’s rebellion, or the mass movement of worshipping an idol called Ba’al Pe’or?

But, that’s not the only challenge. What exactly was the “project” or “perfect realm” of B’Midbar that was tampered with? If the project of Bereishis was the world at large, Shemos was the national covenant at Sinai, and Vayikra was the Mishkan, what is B’Midbar?

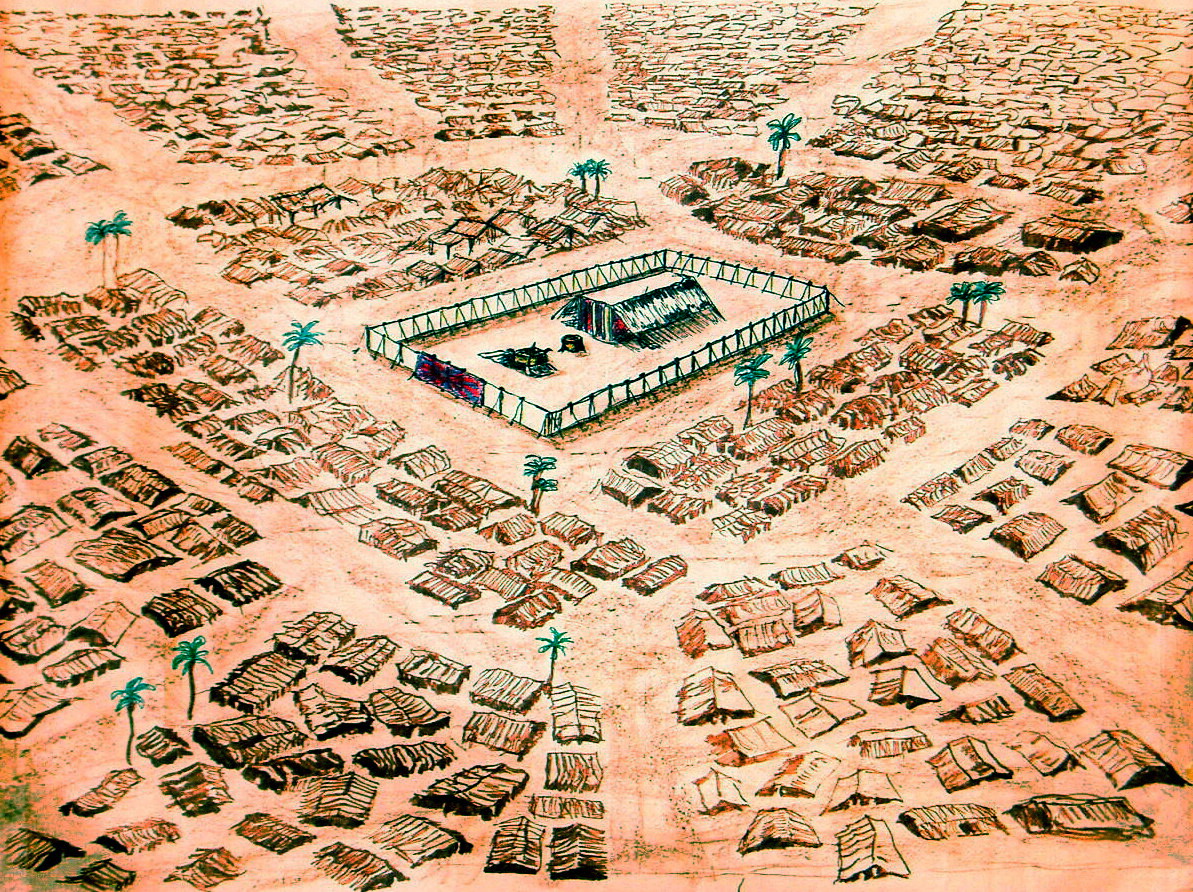

Now, we come to the Census, where the entire nation is divided into their tribal divisions, “Ish Al Diglo”-“a man according to his division” [2:2]. These divisions were made for their travels through the desert. In B’Midbar, no it was not the world at large, nor a Mishkan-structure that was aligned in a certain order. It was the individual people according to their own divisions or tribes. The tribal formation was such so that they would be surrounding the Mishkan for their travels. Such a formation was symbolic of their spiritual responsibilities to make the Torah their center, no matter which tribe a person was a part of. The infrastructure of the diverse tribes, lined up appropriately represented their perfect world. No, they were not created completely “equal,” but that’s okay! Because of their differences, each individual was counted and identified with a different division, each division having a different role from the next. If someone was a Kohein, that’s where he stood, and similarly, a Levi with the Levi’im, a Zevuluni with the tribe of Zevulun, and a Binyamini with the tribe of Binyamin.

But as long as their center was the Torah, each tribe could keep to this perfect order as it was described in the beginning of B’Midbar, the project could endure, and the “goal” we keep on mentioning could have been fulfilled.

Of course, that’s not what happened. At many points, we messed up, and it was the fault of each division of Israel, Levi no less during Korach’s rebellion. And the Torah was careful take narratives from throughout their history, regardless of their chronological order, to demonstrate what happens when members of Israel step out of line, no matter which tribe, and no matter what the circumstance. That’s why B’Midbar is such a complicated book. Because, here, the problem is not mankind, nor the nation at large, but rather, the diverse, individual tribes, struggling to balance their tribal yearnings with their religious responsibilities.

That test was repeated so many times in the Midbar, but really, it is repeated no more than it is in any generation including our own. We’re constantly challenged to unite despite our differences for the sake of the central goal. And often enough, our modern tribalism gets in the way of that central goal, our common relationship with Hashem.

And so, time and time again, the Torah repeats the failures of our people in the desert. And, why? To what end? Looking through the Torah prism from the view of B’Midbar, is the Torah merely trying to tell us that we are eternally doomed to fail this test? No! On the contrary, the Torah is implying that each every mistake that was made was just as equally an opportunity to keep our cool, step back, and redirect ourselves towards the central goal. At any moment in each of the tragedies in B’Midbar, any tribe could have stood up and said “This is wrong,” and no matter how bad things were, perhaps one move in the right direction would have restored order in the camp of Israel.

The initial formation of the tribes around the Mishkan tells us that it can be done. We can right all wrongs in the world if we each put the central goal before our individual tribes. How do we know? Because Chazzal tell us that the formation of the tribes around the Mishkan was actually based on the formation of Yaakov Avinu’s blueprint for how his children stand around his casket when they escorted him to his grave [See Rashi to 2:2 which cites Tanchuma]. Imagine; after a bitter familial feud between Yosef and his brothers, children of Rochel versus children of Leah, children of wives versus children of hand-maidens, etc., Yaakov reveals that we could right every wrong if we set aside our differences and keep our eyes on the central goal. We can do it. And if we can restore that order as individual tribes, we can restore the world to its former glory and perfect our relationship with Hashem.

May we all be Zocheh to each maintain our boundary as individuals and as a a collective people, stay true to our central goal of perfecting our relationship with Hashem, and Hashem should help us restore the world to its former glory with the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos! (Don’t forget to count Sefiras HaOmer.)

-Josh, Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂