This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta

-Miriam Liba Bas Devora

-Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili

-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamah of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus.

בס”ד

הַפְטָרָה שֶל פַּרָֺשַת תַזְרִיעַ

מְּלָכִים ב׳

[4:42-5:19]

“Under His Skin”

While Tazria and Metzora teach about various manifestations of Tumah, or spiritual impurity, the Tumah that gets the most attention in both Sidros is that of the spiritual “leprosy” known as Tzara’as. Chazzal teach us that Tzara’as, which can manifest itself on either one’s skin or even one’s property, plagues the person as a Divine response to one’s sins. The Gemara in Arachin [15B] lists a bunch of particular sins that can cause Tzara’as, the most well-known sin being that of Lashon Hara (slander).

Parshas Tazria and Metzora, however, do not discuss the behaviors which cause Tzara’as. It’s seems to be a purely diagnostic discussion in the Torah. So, suppose the spiritual disease would still be extant nowadays, how would one know how to prevent it and exactly which behaviors to avoid? Is there a special, spiritual diet for Tzara’as prevention? How would we figure it out? We might suggest that the simple key to Tzara’as prevention would be to just live a life of Torah and always fulfill the Will of G-d, which should be our goal anyway, but of course, no one is perfect in that mission, and secondly, if Tzara’as is only triggered by certain kinds of behaviors, that would seem to indicate perhaps a special disdain Hashem for those behaviors which would require stronger concentration.

So, how can anyone begin to determine where exactly Tzara’as comes from? The only way is to assess the available Tzara’as patients. Thus, we know of the association between Tzara’as and Lashon Hara as Moshe Rabbeinu was afflicted Tzara’as after slandering the B’nei Yisrael at the Burning Bush, [Shemos 4:6] and his sister Miriam HaNeviah was afflicted well after slandering him in the desert [B’Midbar 12:10]. The correlation is a strong one. But, as was mentioned, Chazzal mention other causes, between various sinful behaviors (such as bloodshed, false oaths or sexual immorality) and even negative character traits (such as pride and selfishness). Is there any basis for these other catalysts of Tzara’as?

For that, we turn to the Haftaros. There are two major Tzara’as stories in Navi, both somehow involving Elisha the prophet. And as you might expect, one of them is the featured Haftarah for Tazria [Melachim Beis 4:42-5:19], and the other for Metzora [Melachim Beis 7:3-20]. For now, let’s focus on the Haftarah for Tazria to see exactly what it teaches us about Tzara’as.

Before even getting to any discussions relating to Tzara’as, the Haftarah begins with one of Elisha’s many “miracle stories” in which Elisha miraculously causes a loaf of barley to multiply to financially save a community during a famine. Then, the Haftarah tells us about how Elisha cures the Aramean commander, Na’aman, from his Tzara’as affliction.

The first question here is: Who needs the part one of this Haftarah? Yes, it’s a wonderful thing that Elisha performed a miracle for people. He performed many similar acts for many others, but does it really have anything to do with the larger story? If not for the fact that this story was recorded right before the Tzara’as story, we would suggest that it most certainly does not have enough relevance to be in the Haftarah to begin with, so why throw it in there just because of its proximity to the Tzara’as story?

The second question is the one we’ve been wondering until now: How exactly does the larger Haftarah help us understand the Sidrah’s theme of the spiritual impurity of Tzara’as? Yes, Tzara’as is only a featured a few times in Tanach making this piece of Navi a fair candidate for the Haftarah; however, is this story really about Tzara’as? Na’aman happens to have Tzara’as, yes, but is his Tzara’as really a central part of the story or is it just a coincidental detail?

Obviously, we’re going to argue that yes, Elisha’s miracle-work in the beginning of the Haftarah is significant to the larger Haftarah, and that, yes, this Haftarah teaches us a great deal about the function of Tzara’as. So, how is that the case?

As for the story of Elisha and the multiplying barley loaf, we might suggest that the Haftarah is setting the stage to establish Elisha as not just Na’aman’s curer, but as the hero of society at large. This role is important because it makes Elisha the appropriate Tzara’as-healer for the next story, as his community service, like that of the Kohein, represents the antidote to the antisocial behavior of the individual who was afflicted with Tzara’as.

With that introduction, we visit Na’aman, or really, Na’aman visits Elisha. Indeed, the Navi tells us that Na’aman travels to Elisha’s house where Elisha sends a messenger to instruct him to bathe in the Yardein seven times to cleanse him of his disease [5:9-17]. However, Na’aman is strikingly infuriated because he was expecting to see the miracle worker himself come outside, do some magic, and cure the disease [5:10-11]. In this light, we might suggest that perhaps we needed the earlier miracle story to provide the backdrop for Na’aman’s anger that the established miracle-worker refused to miraculously cure him. Needless to say, Na’aman didn’t approve of the simple prescription. Perhaps, we could sympathize. Why did he need to travel all this way to find a prophet and established miracle worker, just so that he could be told by a middleman to take a bath? That should be our question no differently. Why is that Elisha, not only did not perform any miracles to cure Na’aman but, did not even come outside to greet the man who traveled so far to see him. We could only imagine the frustration we might feel if, Chas Va’Shalom, one of our loved ones traveled far out to meet a highly trained medical professional for treatment who wouldn’t even assess the patient personally. What did Elisha have in mind?

Many of the M’forshim explain that Elisha designed the whole event as a humbling process for Na’aman. He was intentionally trying to get under Na’aman’s skin, pardon the pun, to hit a nerve and curb Na’aman’s arrogance. Why was this necessary? Because, apparently, that’s what it would take to truly cure the Tzara’as. That is why the Torah itself commands the individual who has Tzara’as to be isolated from society with his face covered. So, of course Elisha wasn’t going to just entertain Na’aman with a miracle and humor Na’aman’s ego by traveling to him or even greeting him. And when Na’aman was forced to suck in his pride and then patiently and humbly immerse himself, not once, but seven times as he was instructed, only then was he healed. And not only was Na’aman healed, but the Navi tells us that Na’aman renounced his idolatry [5:17].

This Haftarah, thus, tells us a lot about Tzara’as. Indeed, the story is less about disease itself because it is about something far more important which needs to be understood when we read about Tzara’as, and that is about what the Tzara’as affliction implies and how one is to deal with it. It’s not just a skin disease that can be healed by a bath or by any doctor. It is healed by humility and character development.

May we all be Zocheh to truly work on developing our spiritual characters, ultimately mature, and Hashem should help us reach the ultimate state of purity once again with the coming of the Geulah in the days of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

——————————————-

הַפְטָרָה שֶל פַּרָֺשַת מְּצֹרָע

מְּלָכִים ב׳

[7:3-20]

“The Fantastic Four”

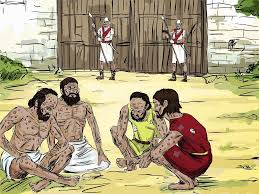

For the Haftarah for Parshas Metzora, we turn to the second Tzara’as story in Navi. This section from Melachim Beis [7:3-20] focuses on what appears to be a side story of four unnamed “Metzora’im,” spiritual “lepers” during the Aramean siege of Shomron.

The Navi tells us that a famine occurred during the siege and that these four Metzora’im reasoned that should they enter the city or remain at the outskirts of town as Metzora’im are typically supposed, they would die from the famine. So, they took the leap of faith and decided to look for food behind enemy lines in the Aramean camp.

Little did they know that Hashem created the simulation of chariot and army sounds which misled the Arameans to ultimately abandon their camp. So, when the Metzora’im got there, they found a ghost town of unguarded food and riches. Understandably so, they began to go from tent to tent, indulging and looting until it dawned upon them that they were acting incorrectly by withholding this news from their city. And, so, they reported back to the city with what they found so that everyone in the city could share in the loot at that desperate time.

The Navi goes on to tell us about how the skeptical captain at the gate of the city, who doubted Elisha’s prophecy that Shomron would soon see an increase in food, ended up getting trampled by the people at the gate.

It’s a nice story with a sort of nice ending, but what does it teach us about the theme of the Sidrah which revolves around Tzara’as? And just as we asked regarding the Haftarah for Tazria, how relevant is it really that the main characters happened to have Tzara’as? Sure, one could argue that the fact that these individuals were Metzora’im was crucial to the story, for had they not been at the edge of the town, they would not have even thought of entering the Aramean camp. But, that’s not really as much a story about Metzora’im, as much as it is about a few risk-takers who were conveniently in the right place at the right time. What does the Haftarah tell us about these Metzora’im?

Moreover, what makes this Tzara’as Haftarah more appropriate for Parshas Metzora than the story of Na’aman whom Elisha cured from his Tzara’as? Conversely, what makes the story of Na’aman a more appropriate Haftarah for Parshas Tazria than this story about the four Metzora’im? We could suggest that Haftaros of these Sidros were merely chosen the way they were to maintain the chronological order as it is recorded in the Navi. There happen to be these two big Tzara’as stories in Navi which stand in close proximity to each other, so it makes sense to give the first one to Tazria and the second to Metzora. Maybe. But, is there perhaps something more fundamental in these two stories that makes each one most appropriate for its designated Sidrah? Both Sidros are about Tzara’as, yes, but is there perhaps a different theme being expressed in Parshas Metzora from that of Parshas Tazria?

It could be that the fact that the four main characters in this story are Metzora’im is quite important. We’re not talking about individuals who just happened to be at the edge of town. They were there for reason, as we explained, because they were Metzora’im. That means that they were sent outside the town because they manifested a spiritual disease that, we’re taught, comes as a result of sin—but not just any sin. As we’ve explained, Tzara’as comes as a result of antisocial behavior, the most well-known one being Lashon Hara, slander. But, it’s not just slander. It could be a whole slew of negative traits and behavior such as pride, selfishness, robbery, and even murder. And because they demonstrated antisocial behavior, they were treated measure for measure and were cast away from society. That is the backdrop for this story as implied by that single but loaded word, “Metzora’im.”

Why is all of that significant? Because it demonstrates how a lowly gang of hungry, societal outcasts develop into the heroes of very society. How did they do that? By overcoming their antisocial tendencies at those fateful moments during the siege. As a result, they would rejoin the society.

In that light, we might suggest that the end of the story which describes the death of the skeptical captain is significant as he can be seen as being contrasted from the Metzora’im. While he remained stubborn, skeptical, and static, the Metzora’im, who like everyone else had nothing left to lose, took the leap of faith and improved their characters.

This story, like that of Elisha and Na’aman, sheds important light on the lesson of Tzara’as, for while the Torah merely tells us about the technical and ritual implications of the disease, but the Navi helps reveal the relationship between Tzara’as and the individual person who has it. In the same vein, while the Torah outlines the technical and ritual purification process, the Navi depicts the equally important maturation process.

So, where lays the thematic difference between the two Sidros and Haftaros of Tazria and Meztora? What do we learn from the story of the four Metzora’im verses the story of Na’aman?

It could be that Tazria and Metzora hint at a two-step process in terms of dealing with Tzara’as. Tazria simply discusses Tzara’as and the isolation process, while Metzora discusses the purification process. How do these two steps manifest themselves in the Haftaros?

Na’aman demonstrates the first step which is to acknowledge the diagnosis. Doing that entails looking into oneself and finding out what’s wrong. We can theoretically point at various sins that triggered the Tzara’as but the attempt to be better would be futile if one does not begin to change the negative Middos or character traits that triggered his sins. Perhaps one sinned to society and therefore got Tzara’as, but, why did he do that? One has to work on the negative traits that trigger the antisocial behavior. For Na’aman, the trait to work on was his humility. He was arrogant, and as such, Elisha designed a treatment process for Na’aman to work on himself.

However, the story of the four Metzora’im may be teaching the second step, that one is to not only supposed to work on one’s internal personality but to actively think about society around him and translate those thoughts into positive actions. Only then can he rejoin society. Tzara’as does not merely end with isolation, thinking about what you did. The goal is not to become a monk, living in solitude. Asocial behavior is not the permanent cure to antisocial behavior. The solution is selfless, prosocial behavior, rejoining society. Thus, the goal of the Metzora and his purification is to rejoin society (which is why, my brother R’ Daniel Eisenberg explains, the Metzora’s purification process mimics the Levite inauguration process, as each procedure is really an induction ceremony into a higher society). This prosocial behavior was demonstrated by the four Metzora’im who could’ve selfishly kept quiet, but instead, shared the news and food with starving city.

What emerges from all of the above is that while Tazria targets the blemish in one’s body and personality, Metzora focuses on correcting the antisocial behaviors and rejoining society.

May we all be Zocheh to not only work on correcting our Middos and growing in our character development, but should engage in selfless, prosocial behavior and not only be heroes to the society around us, but like the Metzora on the day of his purification, Hashem should purify us and induct us into His treasured society of people worthy of Geulah and the coming Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂