| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

אֱמֹר ● Emor

● Why does G-d offer irrelevant information about the laws of damages? ●

“The Curser and the Pre-Curser”

As we just previously discussed, at its very close, Parshas Emor unceremoniously, but quite noticeably, veers off all of its earlier topics to the infamous narrative of the M’Kaleil, or the M’Gadeif, literally, “the one who cursed” the Name of G-d and was executed by stoning.1 Though we spent some time deciphering the narrative of the M’kaleil and its potential backstories, we are going to revisit that narrative and do some further excavating, because we have not completely addressed every issue there is to in this obscure story.

Before we can address the many loose knots in the narrative, one has to ask why Sefer Vayikra so uncharacteristically treats us to this seemingly unsolicited narrative. What does the story of the curser have to do with any of the other topics covered in this Sidrah?

BIRD’S-EYE VIEW: Parshas Emor

In order to get a feeling of the pure disjointedness of this narrative to the Sidrah at large, we have to remind ourselves of what these other topics are. What is Parshas Emor itself about?

- Kedushah & Taharah of the Kohanim and Korbanos2

As we’ve mentioned in previous discussions, Emor begins with the laws pertaining to the holiness and purity of the Kohanim and the Korbanos, for example, how they may only attend funerals in exceptional cases. The Torah also rules that they may not engage in the Avodah SheB’Mikdash if they have certain physical blemishes. Likewise, animals cannot be offered on the Mizbei’ach if they’re blemished.

Beneath this seemingly dry list of technical, Temple-exclusive rules is a deeper message telling us that in various areas of life, depending on the different roles one may play, a higher spiritual standard is required which might necessarily translate into the need for perfection in some of the physical aspects of life.

- The Moadim3

But, the Torah does not believe in religion being only for the “monks.” The Kohanim are only a micro model for what G-d expects from the rest of the B’nei Yisrael who are His “Mamleches Kohanim,”4 His Kingdom of Priests on the macro scale. The rest of the nation too will necessarily have a unique relationship with G-d which will necessarily entail a higher demand for sensitivity of that relationship.

It could be that in this vein, the Torah proceeds to enumerate the laws of the Moadim. In our national relationship with Hashem, as may be in any relationship, each season is filled with meaningful, temporal landmarks which highlight a uniquely different aspect in the history of our relationship; in the month of Nissan, Hashem rescued His beloved B’nei Yisrael from Egypt and we subsequently observe many technical practices to relive the experience on Pesach. We spent forty-nine days preparing for G-d’s revelation at Har Sinai and do the same now to celebrate the anniversary on Shevuos every month of Sivan. The list goes on, but the point is that the relationship which Hashem shares with B’nei Yisrael is reflected in the intricate laws of the annual Moadim. Each of these unique days, like the Kohanim or the Korbanos, are imbued with Kedushah, a holiness that is reflected in the tangible Halachos of the day. That Kedushah is for the entire nation to access.

- The Menorah and Shulchan5

But, just as the Torah was sure to make it clear that holiness was not merely a “priestly” matter, the Torah asserts that, aside from the festivals, the lofty relationship is meant to be reflected as well throughout the year. Thus, coming off the discussion about the Moadim, the Torah emphasizes the laws of the Menorah and the Shulchan which respectively symbolize constant dedication of our spiritual and material lives to Hashem on a daily basis.6

REVIEW: Kedushah and Taharah in Emor

As per all of the above discussions, we are able to identify a running theme between the topics of Emor. Parshas Emor, at large, is devoted to the Kedushah and Taharah, holiness and purity. To recap them quickly, Emor addresses the requisite Kedushah and Taharah of the Kohanim and the Korbanos.2 Then, the it discusses the calendar of the B’nei Yisrael enumerating the Moadim or festivals, highlighting Kedushas HaZman, or holiness as it pertains to time.5 And finally, following the Moadim, the Sidrah records a couple of passages concerning the laws of the Menorah and the Shulchan, the golden candelabra and table, of the Mishkan5, daily reminders of the ideals Kedushah and Taharah.6

Although one may have to do a little bit of connecting the dots, the continuity of Parshas Emor is lucid enough so that there is an intelligible, moving discussion throughout. That is, of course, until we get to the story of “the curser.”

DEAD END: “The Curser”

Indeed, we when we move over to the final topic of Emor, we hit a wall as the Torah tells us about a man born to an Israelite mother and Egyptian father who, for some reason, was either fighting or quarreling with some other Israelite in the camp whereupon he pronounced and cursed G-d’s Name. As the story proceeds, the people would imprison him until Moshe received word from G-d about his verdict. “The curser” would ultimately be liable to stoning and, as such, he was executed.

Let us address the issues with this story.

- External Issue: It’s Placement Here

Before getting to the internal issues concerning this passage, there is an obvious external or “editorial” problem. Aside from the general seeming haphazardness of this story’s placement among the surrounding passages, it is quite striking that the Torah abruptly and randomly interrupts its track of law-related passages to present a narrative. Certainly, the Torah only utilizes its stories for the lessons that are meant to be derived from them, but most of Sefer Vayikra has not followed the format of storytelling. Vayikra, as we’ve explained, has apparently been designated for laws, whether ritual or Temple-related, judicial or societal, etc. In fact, this narrative is the only other narrative present throughout the entire Sefer aside from the story of Nadav and Avihu’s deaths on the eighth day of the Mishkan’s inauguaration. The difference between that earlier narrative and this one is that story of Nadav and Avihu was immediately relevant to the discussions that preceded it and those that followed, namely, the laws pertaining to the Avodah SheB’Mikdash. But, why is the M’kaleil’s story among these Sidros? Why must this story be told at this unpredictable moment, this slot towards the end of Vayikra?

- Internal Irrelevance: The Laws of Damages

Finally, within the story of “the curser,” there seems to be a few verses that are at the very least superfluous, and at worst, unrelated to the topic being discussed in the story itself. The people and Moshe anticipate the fate or the sentence of the apparently guilty curser, and as expected, G-d prescribes the penalty; “Hotzei Es HaM’Kaleil…V’Ragmu Oso…”-“Bring out the curser…and they shall stone him…”7

Then, G-d confirms the general law for the masses; “V’El B’nei Yisrael Tidabeir Leimor Ish Ish Ki Yakleil Es Elokav V’Nasa Cheto. V’Nokeiv Sheim Hashem Mos Yumas Ragom Yirgmu Vo…”-“And to the B’nei Yisrael you shall speak saying: ‘Any man when he shall curse the Name of His G-d he shall bear his sin. And the one who pronounces the Name of Hashem shall surely die; they shall surely stone him…”8

Now, at this point, the Torah should have recorded that the people stoned him and left it at that. End scene. But that’s not what happens, at least not for another few verses. When we think G-d is done talking, or at least should be done talking, He continues to give over various, seemingly simple laws; “V’Ish Ki Yakeh Kal Nefesh HaAdam Mos Yumas”-“And a man, when he shall smite any human being [life] he shall surely die.”9 This law is followed by what happens to one who takes the life of his fellow’s animal, what happens if one merely wounds another, and other such laws.

Thus, apparently, along with the presentation of the law of “the curser,” the Torah included various societal laws. The question is: Why?

First of all, once G-d declared that the man should be stoned to death, it should have been the end of it. Why didn’t He stop there? Second of all, what is the point of teaching these laws here? If the Torah wanted to teach us about penalty for the “M’kaleil,” one law should have been conveyed. Why did the crime of cursing warrant this mini-series of seemingly irrelevant laws?

TRIP PLAN: From the Bottom-Up

Going back to the external issues of the narrative, one point of interest that is worth noting is that if whole point of the narrative was just to illustrate that one should not curse the Name of G-d, it really was not necessary at all. The Torah could’ve simply commanded us not to curse G-d’s Name and that would have been sufficient. Who needs this illustration, whether it is historically what occurred or not? Moreover, as we’ve been arguing, why would change the format from law-code to narrative here and now? And what was is it about the larger discussion of Parshas Emor that called for this narrative?

Answering all of these questions will necessitate our achieving of a richer understanding of “the curser” narrative internally.

Aside from the issue we raised regarding the need for recording the story in the first place, we were bothered by the seemingly extra verses in the law-related part of the story. Hashem could’ve just answered the question and told the people what to do to the M’Kaleil, but instead, He took the opportunity to continue talking about what happens when one person kills another person or damages his property and other such laws. Why did He do this? Where is this theme present in the narrative? Is the narrative not simply about a man who cursed G-d?

EXPLORING: The M’Kaleil’s Untold Backstory

Apparently, the Torah was not merely concerned to tell us a story about a guy who cursed G-d. In fact, more than a mere story about “the curser,” the Torah hints to his untold backstory, the precursor—or the “pre-curser” if you will—to this tragedy.

Who is this M’Kaleil and what is the Torah trying to tell us about him? As was mentioned, the Torah describes this man as being born to an Egyptian man and an Israelite woman. And why does he curse G-d’s Name? Evident from his harsh execution, it must be a pretty terrible thing to do. Why would he have done such a thing?

Unfortunately, the Torah is not clear why he cursed G-d, but it did provide us some textual hints as to what contributing factors his crime. The Torah begins the story by saying that this Egyptian-Israelite “went out” among the Israelites (“Vayeitzei”) and that he ended up fighting with another Israelite, (“Vayinatzu”).

Interestingly, this scene is not the first time the Torah used these textual patterns and themes of “going out” and “fighting.” A while back, the Torah records a story of a man living a similar sort of double life, having both a “Jewish” and Egyptian identity. The Torah tells us that he too “went out” among his brethren, and in the same passage, there was also fighting, “Jew” versus “Jew”; “Sh’nei Anashim Ivrim Nitzim”-“two Hebrew men were fighting.”10 Which earlier story is clearly being echoed in our story?

REVISITING OLD TERRITORY: Moshe in Egypt

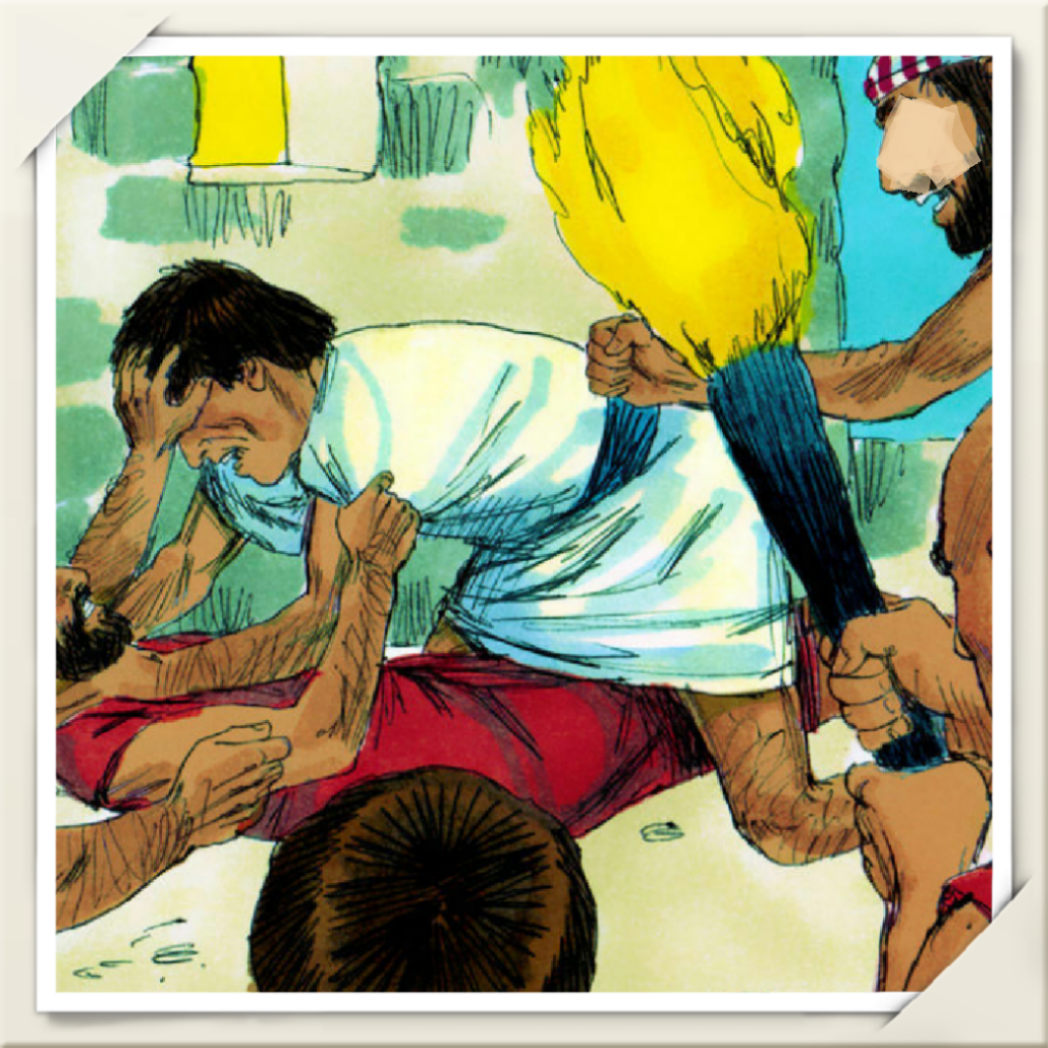

Of course, this is the story of none other than Moshe Rabbeinu during the slavery in Egypt. The Torah tells us about how Moshe went out in attempt to identify with his brethren during their hardships; so greatly did he feel the plight of his people, when he saw an Egyptian taskmaster harming a Hebrew officer, Moshe, the Hebrew “Prince of Egypt,” smote the Egyptian. But Moshe’s attempt to become one with his brethren was to no avail. He saved a fellow Hebrew only to be disappointed later, not only to see two the Hebrews fighting, but to have them disparage him for killing the Egyptian when he tried to mediate their fight. If not for Moshe’s righteousness and Hashem’s harsh assertion that it was his personal responsibility and destiny to save the B’nei Yisrael, he might’ve never reunited with his brethren. Indeed, according to the Midrash, Moshe inferred from the lack of unity and sensitivity between brothers that the B’nei Yisrael deserved to be enslaved.11

With this prequel to “the curser” story in mind, it is quite interesting to note the background details Chazal provide about “the curser.” They suggest that he was actually the son of an illicit relationship between the Egyptian taskmaster and the wife of one of the Hebrew officers during the slavery in Egypt!12 Indeed, he was the son of the Egyptian whom Moshe killed for harming the Hebrew. Chazal must have picked up on some of the hints in the text when they offered their explanation of the story.

INVESTIGATING: “The Pre-Curser”

But what is so telling about the relationship between these two stories is what might’ve led the Egyptian-Israelite man to commit his crime. Among the different suggestions Chazal provide to explain the precursor to the tragedy, one is that this Egyptian-Israelite was attempting to get into the camp of his mother’s tribe of Dan, whereupon he was rejected by them because he lacked paternal inheritance.13 Indeed, by technical, Halachic standards, he was not entitled to inheritance, but at the same time, by Halachic standards, this man was fully “Jewish” or Israelite and should’ve been treated sensitively, with care and concern, especially when all he seemingly wanted to do was become one with and live among his brethren, to identify with them.

While no one covers up for the crime that “the curser” committed, for indeed, he was not just executed, but stoned to death by the law, one cannot ignore the challenge of the situation surrounding him. He sought an identity, at least housing, among his Israelite brothers, and as they did to Moshe, they rejected and ostracized him. Although by the technical standards, they were one hundred percent right and he was one hundred percent wrong, the way they dealt with him was a recipe for disaster and escalated towards just that, from the physical altercation to his cursing of G-d’s Name. Of course he felt estranged and lost hope in “G-d’s people”—it almost happened to Moshe Rabbeinu himself.

CIRCLING BACK: Addressing the Pre-Curser

So, how should G-d respond? Yes, he gives the verdict, but He was not finished. He had to remind the people about the simple laws of humanity and the value of human life in society. Hashem finished off His speech by stating, “Mishpat Echad Yihiyeh Lachem KaGeir KaEzrach Yihiyeh Ki Ani Hashem Elokeichem”-“One ordinance shall there be for you, for the foreigner, like the native shall he be, for I am Hashem your G-d.”14 In other words: Simple humanity! Hashem needs to do discuss this matter because the B’nei Yisrael had become too caught up in the technicalities and “being right” that they had lost track of the primary focus of the Avodos that G-d has authorized them to observe. If a public cursing of G-d’s Name was at stake, the people should’ve never risked such a tragedy. They should’ve been far more sensitive, perhaps even submissive to this isolated Egyptian-Israelite. Yes, G-d included technical laws in our Avodah—there are Halachos in all areas of life. One is commanded to keep to them a Ben Yisrael for it.

THE MIDPOINT OF THE TRIP: Kiddush Hashem and Chillul Hashem

What does any of the above have to do with Parshas Emor? In fact, the Pesukim that serve as the glue which connects the technical laws of Kedushah of the Kohanim and Korbanos with the passages of the Moadim describe the ultimate and most sensitive object of holiness.

“U’Shmartem Mitzvosai Va’Asisem Osam Ani Hashem. V’Lo Sichalelu Es Sheim Kodshi V’Nikdashti B’soch B’nei Yisrael Ani Hashem Mikadish’chem; HaMotzi Es’chem Mei’Eretz Mitzrayim Lehiyos Lachem L’Eilokim Ani Hashem”-“And you shall guard my commandments and do them, I am Hashem. And you shall not desecrate My holy Name, but I shall be sanctified among the B’nei Yisrael, I am Hashem Who sanctifies you; Who brought you forth from the land of Egypt to be for you as a G-d, I am Hashem.”15

Did you catch that? Through proper observance of G-d’s laws, Hashem’s Name is supposed to be sanctified among the B’nei Yisrael, not cursed publicly among them! The same reason why Hashem brought them forth from Egypt was why He allowed this Egyptian-Israelite to join them—that they could serve and sanctify G-d’s Name in harmony. But, that’s not what happened. Instead, the ultimate object of Kedushah was misappropriated, i.e. the Name of G-d. That disgrace of Kedushah all began because one Israelite was not treated like a brother. He cursed G-d’s Name among the B’nei Yisrael, perhaps the only Chillul Hashem greater than the Israelite’s treatment of this man until that point.

The takeaway is simple. Avodas Hashem done has to come with sensitivity and human decency, resulting in a Kiddush Hashem and not the tragic reverse.

FINAL DESTINATION: Profound Sensitivity for Kedushah & Taharah

We’ve said that the Torah’s focus on Kedushas Kohanim sets the tone for Klal Yisrael to live life on a higher level. In the same way, the Torah calendar is modeled after the relationship Hashem shares with His people, the very relationship that makes Klal Yisrael unique and obligates them exist on that higher plateau. If we simply turn around and forget this higher purpose of the Torah’s technicalities when we observe them and allow fellowman, Jew or not, to be publically insulted, G-d’s Name is NOT sanctified as a result. You get a “M’Kaleil” story as a result. You get the same confirmation that Moshe Rabbeinu had that the B’nei Yisrael were undeserving to be rescued from Egypt and become G-d’s special people in the first place.

The story of “the curser” is what happens when basis for Jewish observance is forgotten. It is the story of someone who felt that he was not surrounded by G-d’s Mamleches Kohanim. It is a calling for us to reevaluate the goal of our personal Avodos and subsequently allow G-d’s to be sanctified among the B’nei Yisrael.

May we all be Zocheh to have an observance of Avodas Hashem that is founded on compassion and human decency, and it should become a source of praise and sanctification to Hashem’s Name and us as His beloved people, and it should likewise be a source for the swift arrival of the Geulah in the days of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Vayikra 24:10-23

- Vayikra 21-22

- Vayikra 23

- Shemos 19:6

- Vayikra 24:2-9

- For more on the relevance of the Menorah and Shulchan in Parshas Emor, see what I wrote earlier; “Kedushah, Taharah, and the Day-to-Day.”

- Vayikra 24:14

- 24:15-16

- 24:17

- Shemos 2:11-14

- Rashi to Shemos 2:14 citing Shemos Rabbah 1:30

- See Shemos Rabbah 1:28, Sifsei Chachamim to Vayikra 24:10; See also Vayikra Rabbah 32:4.

- Rashi to Vayikra 24:10 citing Toras Kohanim 14:1, Tanchuma 24, and Vayikra Rabbah 32:3

- Vayikra 24:22

- Vayikra 22:31-33