| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah-Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

שְׁלַח ● Shelach

● Why does Parshas Shelach send us off with the Mitzvah of Tzitzis? ●

“Fringes of Faith & Faithfulness”

It is not always easy to predict, without hindsight knowledge of the Mesorah, where a new Sidrah should have reasonably begun in the Torah. But even where we could have, on our own, determined correctly where a Sidrah should have begun, it is even more difficult to predict where a given Sidrah should reasonably end. Of course, every now and then, we can ascertain and speculate where a fair stopping point presents itself, but again, it is mostly speculation. However, Parshas Shelach, as we will see, is a rare case where the Sidrah seems to implicitly demarcate its own conclusion.

GLOBAL VIEW: What’s in a Sidrah?

When a cap is placed on a Sidrah, an assumption which we would like to be true is that the given “chapter” of the Torah has reasonably ended and whatever appears between the beginning of the Sidrah and its conclusion reasonably belongs within the bounds and umbrella of that Sidrah’s unifying theme and topic. Obviously though, not all of the Sidros, at least at first glance, appear to have been divided so smoothly. Sometimes, one has to work harder to appreciate the wisdom behind the division of Sidros.

Parshas Shelach, for example, seems to really be split between multiple different topics. The climax seems to appear early on with the single topic of the Cheit HaMiraglim.1 After that tragedy is recounted though, the Chumash veers off to discuss various law topics, some pertaining to Korbanos2, the Mitzvah of Challah3, and the various procedures for atonement for the violation of the capital crime of Avodah Zarah.4 Then, the Sidrah records a seemingly random incident of Shabbos desecration in the wilderness, of all topics.5

Various commentators offer suggestions to explain the juxtaposition of topics as well as why the Sidrah marked by the Cheit HaMiraglim would reasonably feature such topics altogether. However, as was mentioned, if there is one thing we can be sure about, it is is that if one looks closely, there is an apparently unmistakable conclusion to Parshas Shelach in the last section. That section is the Parsha of Tzitzis.6

TODAY’S SITE: The Parsha of Tzitzis

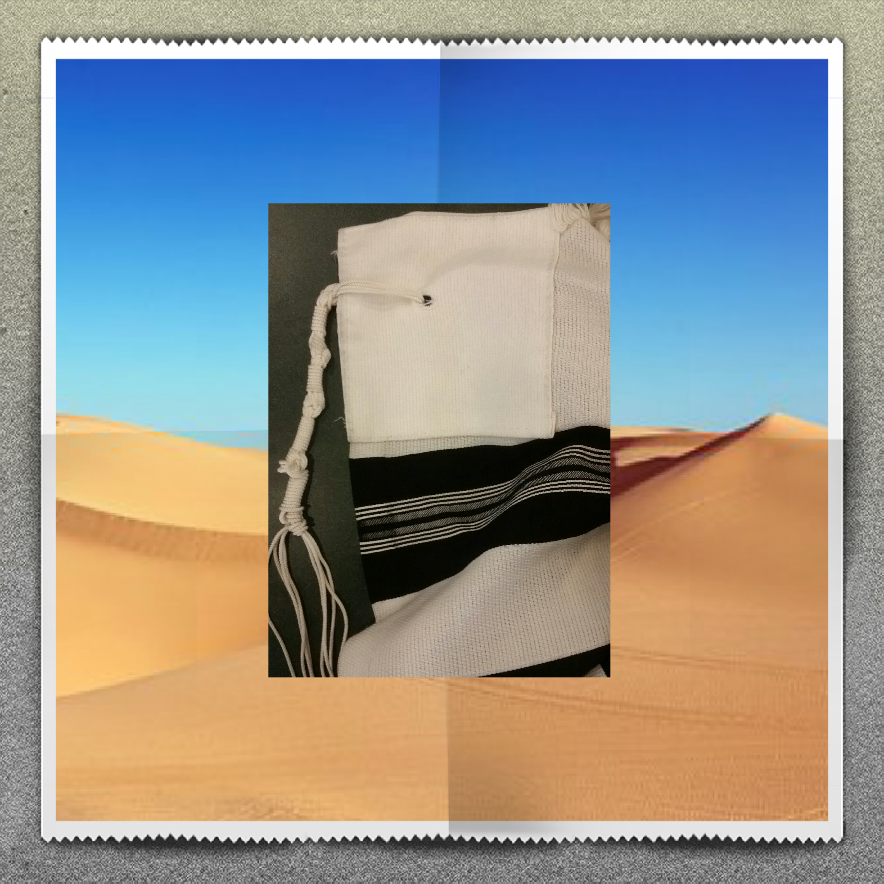

The Parsha of Tzitzis is where Hashem relates to Moshe the Mitzvah of Tzitzis, which are complexly knotted and wound fringes which all Jewish males are commanded to hang at each of the corners of their four-cornered garments.

Now, what makes Tzitzis the unmistakable conclusion to the Sidrah of the Cheit HaMiraglim? The suggestion that there is any relationship between the Cheit HaMiraglim and the Mitzvah of Tzitzis seems almost sarcastic, but it is not at all. For anyone who is aware of the textual parallels, whether one noticed it on his own, or whether someone else pointed it out to him, the basis for the connection is so clear that one can no longer un-notice it.

THE TRAIL: Between the Sin of the Spies & Tzitzis

If one looks back at the account of the Miraglim, the Chumash writes, “…Viyasuru Es Eretz Cana’an…”-“…and they shall spy out the land of Cana’an…”7—that the mission of the Miraglim was one of “spying out.” This expression of “spying out” would appear in subsequent verses throughout the story as the Torah relates, “Vayishlach Osam Moshe LaSur Es Eretz Cana’an”-“and Moshe send them to spy out the Land of Cana’an”8 and “Vayashuvu MiTur HaAretz…”-“and they [the spies] returned from the scouting [spying] of the land…”9 This term of “spying out,” uncommon it is throughout the Torah, is the clear theme of the Miraglim narrative.

Well, if one looks at the end of our Sidrah, in the passage of the Tzitzis, after the Torah instructs us that we should see the Tzitzis, remember G-d’s laws and perform them, the Torah warns us, “…V’Lo Sasuru Acharei Levavchem V’Acharei Eineichem…”-“…and you shall not spy out after your hearts and after your eyes…”10 clearly echoing and seemingly warning against a repeat of the mission of the Miraglim.

Even Rashi seems to have not only recognized the conspicuous connection between the Miraglim and Tzitzis, but to have even called that connection to our attention in case we didn’t notice it ourselves. Indeed, Rashi comments, in the passage of Tzitzis, that the expression of “Sasuru” means spying out, and he proves it using a Pasuk from the Cheit HaMiraglim narrative as the reference. This is particularly telling as Rashi neglects to use an even earlier verse from last Sidrah, Parshas B’Ha’alosecha, where the expression of spying or scouting out was also used, as the Chumash stated there, “…VaAron Bris Hashem Nosei’a Lifneihem Derech Shloshes Yamim Lasur Lahem Menuchah”-“…and the Aron of the Covenant of Hashem traveled before them a three-day distance to scout out a resting place for them.”11 Rashi seems to prefer the verse in our Sidrah, perhaps in order to acknowledge the particular connection between the beginning and end of Parshas Shelach.

Should one argue that the above is a mere coincidence, the rest of Rashi’s comments on our Tzitzis passage spell out everything as Rashi explains that the eyes and the heart, referenced in the Pasuk, are the “Miraglim” or “spies” for the body, scouting out potential sins, so that the eyes see, the heart wants, and the body ultimately acts upon the desire to sin.12 His deliberate usage of the word “Miraglim” is almost bone-chilling.

EXPLORING: The Deeper Connection

Now that we know that there is a connection between the Miraglim and the concluding passage of the Sidrah which describes the Mitzvah of Tzitzis, the question we have to consider is why these parallels between the Miraglim and Tzitzis exist? The association is clear, but what is its meaning? Indeed, it seems as though the entire Mitzvah of Tzitzis, if not instituted completely in response to the tragedy, was a Mitzvah that uniquely speaks to the Cheit HaMiraglim. Hashem Himself wanted us to be aware of the conversation between the Cheit HaMiraglim and the Mitzvah of Tzitzis. Textually, they are connected, but what does Tzitzis actually have to do with the Miraglim? How does Tzitzis respond to the Miraglim? What is the Torah is trying to teach us by walking us out of Parshas Shelach with this unique topic of Tzitzis?

POINT A: The Mission of the Miraglim

In order to understand the deeper connection between the Miraglim and Tzitzis, we have to understand what was fundamentally wrong with the mission of the Miraglim.

As we’ve seen, matters went from bad to worse between Parshas B’Ha’alosecha and Shelach. The downward spiral had begun with simple complaining in the wilderness, but met its all-time low with the Cheit HaMiraglim. Although Hashem apparently authorized or gave permission for Moshe to send Miraglim into Cana’an7, the fuller story, as it is presented in Sefer Devarim13, the idea was presented by the people who bombarded Moshe, demanding that he send scouts in. Why Hashem ever allowed Moshe to send in Miraglim is a separate, but important issue14, but Chazal agree invariably that the whole mission was never ideal from the outset.15 It was a disaster waiting to happen.

What was so fundamentally wrong with the mission of the Miraglim? The entire request stemmed from a lack of faith in Hashem. The B’nei Yisrael’s loss in faith began to surface when they lost their patience in Parshas B’Ha’alosecha but had completely revealed itself at the scene of the Miraglim. Perhaps we could have argued that sending in scouts was a reasonable request so that the nation could devise a natural game plan to conquer the inhabitants of the land. But, the way the people reacted to the reports of the Miraglim demonstrated that all along, the mission behind the Miraglim was never truly about how to, but if they would ultimately agree to following Hashem into the Promised Land. That was why they urged Moshe to send people ahead into the Land of Cana’an—to spy it out its inhabitance, fortification, produce and any other determining factors that would qualify or disqualify the land as a suitable homeland for conquer. And when the Miraglim returned later with a negative, discouraging report, the lack of faith would finally expose itself and the people would turn their backs on G-d’s Promised Land.

POINT B: Fringes of Faith

If the problem with the mission of Miraglim was lack of faith in G-d and devotion to His mission, the response and the Mitzvah of Tzitzis would have to represent complete faith in G-d and complete devotion to His mission, which indeed, it does.

Beyond a collection of strings, what are the Tzitzis? What is their purpose? In our passage, the Torah uncharacteristically elaborates on that exact purpose of the Mitzvah telling us, “U’Re’isem Oso U’Zechartem Es Mitzvos Hashem Va’Asisem Osam…”-“and you shall see it and you shall [subsequently] remember the commands of Hashem and [ultimately] perform them…”10

In other words, the Tzitzis are supposed to serve as eye-catching reminders for us to do Hashem’s Mitzvos. Thus, in one of his explanations, Rashi suggests that the word “Tzitzis” is actually derived from the word “Meitzitz,” which means to peek or peer at something.16

How might these strings remind us to follow Hashem’s commandments? Many suggestions are offered. For example, Rashi teaches famous that word Tzitzis contains a Remez or hint to the six hundred thirteen Mitzvos of the Torah, as the numerical value of “Tzitzis” (600), plus the eight fringes (+8) and the five knots (+5) in each set of fringes comes out to a total of six hundred thirteen.17 Ramban suggests an answer, equally famous, based on Chazal’s teaching, that the Techeiles, or the turquoise fringe in the Tzitzis18 is meant to remind its viewer of the seas which reflects off the sky which reminds one of G-d’s Thrown of Glory.19 Thus, by looking at the blueness of the thread, one is constantly reminded of G-d’s Divine Presence.

In a simpler, more down-to-earth approach, Alshich suggests that the strings of the Tzitzis can be likened to the string one colloquially ties on one’s finger when he needs to remember something; in this case, it is the Mitzvos.

Perhaps even more fundamentally, R’ Shimshon Raphael Hirsch suggests an approach which highlights how the garment is a prerequisite for Tzitzis. He explains that the first clothes that ever existed were the ones which G-d made for Primordial Man after he sinned, making them a reminder and covering of his shame of his nakedness which he only first experienced after he violated G-d’s command. Thus, clothing, and now the Tzitzis, would be a permanent reminder to follow G-d’s commandments.

Clearly, Tzitzis were meant to serve as a reminder for one to fulfill Hashem’s Mitzvos. But, what intrinsically does that have to do with having faith in G-d? At first glance, one might say that it has everything to do with faith in G-d, because one will only commit to doing the Mitzvos if there is a basis, namely, if he has faith in G-d. Is that where faith plays a role here? Is the idea that one’s observance of the Mitzvos demonstrates his faith in the Commander? Because if that is the case, why did the Torah need to include this seemingly extra step of “remembering the Mitzvos” as a demonstration of faith? If the real issue the generation had was a simple lack of faith, then the Torah should have focused more on the topic of faith, and less on that of observance of Mitzvos. And was that not the case, that people were afraid to enter the land because they didn’t have faith in G-d?

Thus, perhaps a better passage to place at the end of Parshas Shelach and a better response to the Cheit HaMiraglim would have been the passage of “Anochi Hashem Elokeca Asher Hotzeisicha MeiEretz Mitzrayim MiBeis Avadim”-“I am Hashem your G-d Who brought your forth from the land of Egypt from the house of bondage”20—the Mitzvah of Emunah BaHashem, faith in G-d. Then, the Torah could have followed up with, “…and you shall not spy out after your hearts and after your eyes…”10 as we described earlier. Maybe, the end of Shelach would have been an appropriate time for the Torah to have taught the Mitzvah of Krias Shema, the declaration of the Unity of G-d.21 Did we really need Tzitzis specifically or these “reminders” of the Mitzvos specifically to reinforce the message of faith?

FOLLOW THE PATH: Between Faithless & Faithless

In yet another parallel between the Cheit HaMiralgim and the Parsha of Tzitzis, we will discover that it the faith of the nation had everything to do with their observance of Mitzvos or the lack thereof. This one is far more subtle and perhaps more astounding.

In the fallout of the Cheit HaMiraglim, Hashem admonishes the generation that they would die and that their children would wander before they would earn the opportunity to enter the Promised Land. In this sentence, Hashem declared, “V’Nasu Es Z’nuseichem”22 which Rashi and Targum Onkelus render, “and they will bear your guilt.” Rashi adopts Onkelus’s reading as apparently, they were both bothered by the most literal translation of this verse which would read, “and they shall bear your licentiousness” or “your harlotry.” Indeed, the word “Z’nus” is the basis for the word “Zonah” which means a harlot. It makes sense that for one to be bothered by this read in our verse because what sexual infidelity was committed amidst the Cheit HaMiraglim? The people engaged in slander at worst; at the very least, they lacked faith and were just afraid of the inhabitants of the land. Should that be equated with adultery?

And yet, in the passage of Tzitzis, we find the same seeming connotation of infidelity alluded to. If we look at the rest of the verse we’ve been citing until now in its entirety, it reads, “V’Lo Sasuru Acharei Levavchem V’Acharei Eineichem Asher Atem Zonim Achareihem”-“…and you shall not spy out after your hearts and after your eyes, that which you stray after.”10

Here, the common translation for the same term is to stray, but again, the word fundamentally means to act with licentiousness or disloyalty, like an adulterer. The challenge here though is the same as the one we raised concerning the Cheit HaMiraglim and that is: Where exactly is the act of adultery in this passage? The Tzitzis are supposed to be a reminder of the Mitzvos. What do they have to do with not committing adultery?

The answer to this question will bring us back to the fundamental relationship between faith in G-d and observance of His Mitzvos. Earlier, we were wondering why remembering and observing the Mitzvos was a necessary part of the response to the Miraglim and the nation who lacked faith in Hashem. Of course we want the B’nei Yisrael to perform the Mitzvos, but isn’t the main issue here one of faith?

The truth is that we can ask the same question about the fundamental relationship between faith in G-d and “infidelity,” the sin that we know the people committed and the sin the verse seems to blame them for. What is their relationship? Is it just that one who has faith in G-d will not be disloyal? One who has faith will not commit adultery? Perhaps there is something even more fundamental.

It could be that the more fundamental relationship between faith in G-d and the concept of infidelity is related to the two meanings of the English word “faithless,” which, we might propose are interrelated. If someone is faithless or acts with faithlessness, that could literally mean one of two seemingly different things. To be faithless either means to not be faithful, i.e. to be disloyal. Or, it could mean to simply not have faith, to not trust. In the Hebrew language, this is simply the difference between one who is Ne’eman, trustworthy or faithful, and someone who is Ma’amin, having faith in someone or something else. One means to be someone who can be trusted, the other means someone who trusts.

Now, we supposed earlier that the connection might be that when one is lacking faith in G-d—that is when he tends to act faithlessly or disloyally toward Him, violating His Will. Indeed, this could be the case. However, perhaps often enough, the reverse is equally true, that because one tends to act faithlessly against Hashem, through cognitive dissonance, he ends up neglecting to have faith in Him altogether.

If all of the above is true, what are our verses suggesting? If one thinks about it, “Z’nus” connotes the opposite of both faith and faithfulness. A “Zonah,” a harlot, is woman who commits adultery, faithlessly straying from her husband. Clearly, through her infidelity, she has demonstrated that she is not one to be trusted; she is not faithful. But, perhaps, at some point in time, whether before or after her faithless act, she manifested her own lack of faith in her husband. On the one hand, if she truly believed in him—that he would always be there to care for her and meet her needs, perhaps she might have never have been so disloyal. And yet, on the other hand, perhaps it was the other way around; only after she acted disloyally did she begin to project her own disloyalty onto her husband, allowing herself to lose faith in him, so that if she herself had only been more loyal, she would never have lost faith in her husband.

CIRCLING BACK: The Dual Faithlessness of the Nation

Perhaps we can argue that either of these two possibilities if not both were true for the B’nei Yisrael at the scene of the Miraglim. Perhaps, as we suggested earlier, the people had a lack of faith in G-d and therefore, they would not commit to His command that they enter the land. But, maybe, their lack of faith stemmed from their own disloyalty to the Mitzvos. In other words, since they had a disloyal disposition toward the Mitzvos, they therefore displayed a lack of faith in Hashem.

That would support the wild allegation which Moshe would later reveal that the B’nei Yisrael made against Hashem at that time, “B’Sinas Hashem Osanu Hotzi’anu MeiEretz Mitzrayim”-“out of Hashem’s hatred for us, He brought us forth from Egypt.”23

Indeed, because the people themselves were faithless, i.e. disloyal, they became faithless, i.e. lacking trust in G-d, accusing Him of disloyalty. Because they were not themselves Ne’emanim, they ceased to be Ma’aminim. It was with this dual faithlessness that they demanded that spies be sent to scout out Cana’an. On that basis, they strayed after their hearts or desires as well as their eyes or their false perceptions. Their latent motivation or their “Evil Inclination” was to find any pretext that can get them out of their commitment to the Mitzvos, entering the land. Consequently, they had no faith, disregarded G-d’s Divine Providence and His command that they venture forward.

This faithlessness and the need to “spy out” as a prerequisite for Hashem’s Mitzvos is what the Torah here discourages in the Parsha of Tzitzis. The disloyalty against the Mitzvos and the lack of faith in Hashem are reciprocal variables of vicious cycle that is counteracted by Tzitzis. The Tzitzis remind us that if G-d either guarantees something or sends us on a mission—in the case of the Miraglim, it was both—then the only option is to proceed with faith. That does not mean that it is not okay to make sure that the coast is clear so that one can accomplish the mission; however when the spying out is to see if G-d’s command sits well with us, to see if we will fulfill altogether, that is both an expression of faithless in G-d and faithless towards G-d.

FINAL DESTINATION: Faith & Faithfulness

In one final parallel between the Cheit HaMiralgim and Tzitzis, we have a reference to the Exodus from Egypt. In a most vital reminder, the Hashem declares: “Ani Hashem Elokeichem Asheir Hotzeisi Es’chem Mei’Eretz Mitzrayim Lihiyos Lachem Leilokim Ani Hashem Elokeichem”-“I am Hashem your G-d, Who brought your forth from the Land of Egypt to be for you a G-d; I am Hashem your G-d.”24

Indeed, it was that same Exodus which the generation of the Miraglim sought to undo. But, in light of the above discussion, we might suggest that they sought to undo the second part of that verse, namely to remove Hashem from being a G-d to them.

In this vein, we are commanded to remember Yetzias Mitzrayim or the Exodus from Egypt constantly. Because, based on everything we’ve discussed, we can suggest two crucial reasons why we must remember. The first is that the Exodus became the foundation for our complete faith in G-d, thus we sang His praises at Sea of Reeds and marched through the wilderness. That is what the Navi recounted, “Lechteich Acharai BaMidbar B’Eretz Lo Zaruah”-“your following Me into the wilderness, into a land that is unsown.”25 And yet, the second reason is that Exodus was the foundation for our faithfulness, how we would demonstrate our acceptance of Hashem as a G-d by devoting our lives to the fulfillment of His Mitzvos, how G-d became a G-d to us.

Unfortunately, neither the faith nor the faithfulness was present when the B’nei Yisrael were at the cusp of entering the Promised Land. But, that is where we rearrive at the Parsha of the Tzitzis. Here, the Torah urges us, at the close of Shelach, to take these Tzitzis which remind us dually of the faithfulness we must display toward G-d through our observance His Mitzvos, and the faith we must have in Him. When we can instill in ourselves both this steadfast faithfulness toward G-d and the faith in G-d to match it, we will once again be welcomed into His Promised Land.

May we all be Zocheh to take the lesson of Tzitzis by developing a true sense of faith in G-d and faithfulness to Him through observance of His commandments and we will have the confidence and merit to pick up where Klal Yisrael and the Miraglim left off as we enter the Promised Land soon, in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bamidbar 13-14

- 15:1-16

- 15:17-21

- 15:22-31

- 15:32-36; for more on the relevance of this topic, see the previous piece titled, “The Mystery of the Wood Gatherer.”

- 15:37-41

- 13:2

- 13:17

- 13:25

- 15:39

- 10:33

- To 15:39 citing Tanchuma 15

- Devarim 1:22

- As for why Hashem permitted Moshe to send in Miraglim if doing so was a dangerous idea from the outset, see what I wrote earlier in the entry titled, “Mission Possible.”

- See Rashi to 13:2 citing Tanchuma 5 and Sotah 34B.

- Citing Sifrei 115 based on Shir HaShirim 2:9

- Citing Tanchuma, Korach 12. See the explanation of this source offered by Tur, Orach Chaim 24.

- Bamidbar 15:38

- Menachos 43B

- Shemos 20:2

- Devarim 6:4

- Bamidbar 14:33

- Devarim 1:27

- Bamidbar 15:41

- Yirmiyah 2:2