| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben Yosef A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -MY BROTHER: MENACHEM MENDEL SHLOMO BEN CHAYA ROCHEL -HaRav Gedalia Dov Ben Perel -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Yechiel Baruch HaLevi Ben Liba Gittel -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -And all of the Cholei Yisrael, especially those suffering from the COVID-19 Pandemic -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

פֶּסַח ● Pesach

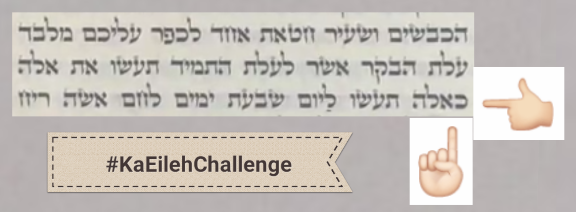

“The #KaEilehChallenge”

“מִלְּבַד֙ עֹלַ֣ת הַבֹּ֔קֶר אֲשֶׁ֖ר לְעֹלַ֣ת הַתָּמִ֑יד תַּֽעֲשׂ֖וּ אֶת־אֵֽלֶּה

כָּאֵ֜לֶּה תַּֽעֲשׂ֤וּ לַיּוֹם֙ שִׁבְעַ֣ת יָמִ֔ים לֶ֛חֶם אִשֵּׁ֥ה רֵֽיחַ־נִיחֹ֖חַ לַֽה׳ עַל־עוֹלַ֧ת הַתָּמִ֛יד יֵֽעָשֶׂ֖ה וְנִסְכּֽוֹ”

“Aside from the Elevation offering of the morning that is [served] as the [regular] continual Elevation offering, you shall perform these; like these shall you perform for the seven-day period, bread of a fire offering, a pleasing fragrance to Hashem, aside from the [regular] continual Elevation offering, it shall be performed and its libation.”

On a given day of Pesach, for better or for worse (Halachically speaking it is definitely for worse), during the Krias HaTorah, one can often hear the resounding echoes following the Ba’al Kriah’s reading of the word, “Ka’Eileh.” The urge for the congregation to sing along with this particular word (which, again, is not Halachically acceptable) is an absolute enigma. The word literally just means “like these.”

Perhaps the word resonates because of its repetitive nature, as it appears immediately following the word “Eileh” of the previous Pasuk. Perhaps it has to do with the fact that it opens the Pasuk with a noticeably unusual Trop or Cantillation note, the “Azla Geireish” [ ֜ ] which rarely appears at the beginning of the verse. Maybe it’s both.

Regardless, though it seems that this year, due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, we will not be hearing this word in the forum of Krias HaTorah, neither from the Ba’al Kriah, nor from a mindless congregation that just cannot help itself, considering the attention this word is getting on social media with the spread of the ridiculous #KaEilehChallenge, perhaps it is an opportune time to get a legitimate Torah perspective on the significance of this word. With that said, what exactly is the meaning of “Ka’Eileh”?

In the Maftir paragraph of the Pesach Torah reading, the Torah elaborates on the Musaf offering or “additional” offering of Pesach/Chag HaMatzos.1 After describing the Korban, the Torah declares:

“Milvad Olas HaBoker Asher L’Olas HaTamid Ta’asu Es Eileh; Ka’Eilah Ta’asu LaYom Shiv’as Yamim Lechem Isheih Rei’ach Nicho’ach LaHashem V’Nisko”-“Aside from the Elevation offering of the morning that is [served] as the [regular] continual Elevation offering, you shall perform these; like these shall you perform for the seven-day period, bread of a fire offering, a pleasing fragrance to Hashem, aside from the [regular] continual Elevation offering, it shall be performed and its libation.”2

The word “Ka’Eileh” (“Like these”) in this passage is actually noteworthy because it is unique to the Musaf of Chag HaMatzos. Indeed, if one looks at the Musafim of all the other festivals, one will not find this word. What unique feature of this Musaf was the Torah trying to emphasize with the word “Ka’Eileh”?

Partner Holidays

The Midrash3 explains that unlike Parei HaChag (lit., Bulls of the Festival) that are offered in the Musaf of Succos4 which diminish in number each passing day of the seven-day festival, the formula for the Musaf of Pesach or Chag HaMatzos remains the same for all seven days. Thus, “like these”—in otherwise, according to these instructions—“you shall perform each day of the seven-day period.”

Though this Musaf is clearly one of the few key differences between Chag HaMatzos and Chag HaSuccos, the two festivals share an intimate connection with one another. Consider the many parallels they share.

- 7-Day Holiday

Chag HaMatzos and Chag HaSuccos are the only two Biblical holidays which last seven days (eight days in the Diaspora).

- Chol HaMo’eid

They are the only two holidays which have a group of intermediate days known as Chol HaMo’eid (lit., “Mundane of the Festival”) which has a combined status and ruleset of both festival and weekday.

- Zeicher L’Yetzias Mitzrayim

Moreover, both holidays are especially linked to the commemoration of Yetzias Mitzrayim, the Exodus from Egypt.5

- The 15th / “Beginning of the year”

Both fall out on the fifteenth of the month, and indeed, the Gemara compares them for the sake of deriving rules between the two days on the basis of this commonality.6 Moreover, they do not merely fall out at the same time of the month, but each month that the two holidays fall out in, in its own way, represents the beginning of the year, as Pesach falls out in the month of Nissan, which the Torah deems the first month of the year7, while Succos falls out in the month of Tishrei in which we celebrate Rosh HaShannah (lit., the Head of the Year).

- The Number Four

Furthermore, various customs of both holidays ascribe significance to the number four (on Succos, there is a commandment to take four species, there are four walls maximum to a Succah, etc., and on Pesach, there are four questions asked at the Seder, four cups of wine corresponding to four expressions of redemption in the Exodus story, four sons described in the Haggadah, etc.).

- Bread Limitations

Among many further parallels between the two festivals (we unfortunately won’t be addressing them all here), perhaps the most striking is that the main Mitzvah of each day entails some kind of limitation on our consumption of bread. While for the seven days of Pesach, one is supposed to eat Matzah, unleavened bread, and all Chameitz, or leaven, is forbidden for consumption, for the seven days of Succos, one is supposed to live and eat his food in the Succah, and no bread is to be eaten outside the Succah. So, while on Pesach, the concern is within the bread we eat, on Succos, the concern is the conditions under which we eat the bread.

- Rabbeinu Chananeil: “Maggid”

Now, if there are not enough ties between the two holidays already, Rabbeinu Chananeil confirms the association for us in his astounding comments concerning the commandment of Succah.8 The Torah commands us to perform Succah “so that your generations shall know that I [Hashem] caused the B’nei Yisrael to dwell in booths when I took them from the land of Egypt…”9 to which Rabbeinu Chananeil suggests the following:

“…it [the knowledge referenced in the verse] is a [basic] knowledge for the generations, as if to say, [concerning] the coming generations, [that] when they see that we are making Succos, and we leave the houses of our [usual] dwelling, and we sit, during the days of the Festival, in the Succah, they will ask: ‘Why are we doing this?’ and their fathers shall relate [U’Maggidin, ומגידין] to them the event of the Exodus from Egypt.”

Indeed, the goal of relaying the meaning behind the practice of Succah, as overtly formulated by Rabbeinu Chananeil, incredibly echoes the exact formula of the Pesach Haggadah which is famously arranged in the question and answer format in which the meaning of Pesach is related between father and son in the context of the story of the Exodus from Egypt! Undeniably, this excerpt sounds a lot like the question of the “Simple Son” during the Maggid [מגיד, lit., Relate] portion of the Seder (and just for good measure, Rabbeinu Chananeil utilizes the expression of Maggid; “U’Maggidin [ומגידין] Lahen”-”And they shall relate to them”).

Considering these fascinating parallels, what is the fundamental difference between the two festivals? And how is this difference apparently highlighted by their differing Korbanos?

Chag HaMatzos vs. Chag HaSuccos

Returning to the iconic Mitzvos of the two holidays, Matzah and Succah, they share another similarity besides for the fact that they entail limitations on our bread consumption. Both the Matzah and the Succah represent simplicity and spirituality. The Matzah is a “poor man’s bread” and the Succah which is just a hut, is effectively a “poor man’s house.” Each one de-emphasizes physicality and materialism. The difference between the Mitzvos is their relationship to the people observing them. Matzah enters the observer’s body and impacts him internally, whereas Succah surrounds him and impacts him externally. What is the meaning behind this difference between Matzah and Succah, the Matzah representing the “internal” and Succah, the “external”?

Perhaps Matzah and Succah are designed to counteract two different, negative spiritual forces, each referenced in the supplication of R’ Alexandri, who prayed as follows:

“Master of the worlds, it is revealed and known before You that our will is to do Your Will, but who is withholding [us]? The yeast that is in the dough [Se’or SheB’Isah], and the subjugation of the [gentile] kingdoms [She’ibud Malchiyos]. May it be the will before You that You shall save us from their hand, and we shall return to perform the statutes of Your Will with a whole heart.”10

While Matzah counteracts the internal inclination which is symbolized by Chameitz, the “yeast in the dough,”11 the Succah shelters us from the external threat, the subjugation of the enemy nations. With this dichotomy established, let us return to the respective Korbanos of the two holidays.

Succos: Israel vs. External Enemies

As far as the Musafim of Succos is concerned, Rashi12 points out that the Parei HaChag would provide protection for the seventy nations of the world. However, the diminishing number of the Parei HaChag represents the sequential annihilation of those nations who oppose Hashem’s will and oppress His nation.

This offering perhaps implies that Chag HaSuccos represents Hashem’s embrace which shelters us from the dangers of the outside world, especially the enemy nations. If so, what is the hallmark of Pesach? Why, on Chag HaMatzos, does the formula for the Musaf remain constant?

Pesach: Israel vs. Internal Inclination

Ultimately, once we have truly become Hashem’s people and surrounded ourselves with a pure environment do we actively earn Hashem’s protection. But that protection was not solidified overnight. Moreover, such a shelter would have proven futile if built prematurely. That is because a shelter is useless if the threat has already made its way inside—if the threat is yet present internally.

In this vein, before we became worthy to build our protective Succos, we had to endure an “internal” process of Chag HaMatzos. What exactly does that process entail and why was it necessary?

Apparently, Pesach is not primarily about our battle against the nations of the world, though, no doubt, the Haggadah acknowledges, “SheB’Chol Dor VaDor Omdim Aleinu L’Chaloseinu”-“that in every single generation, they stand against us to annihilate us.” Pesach is primarily about our struggle against Ancient Egypt, but not just as an oppressive nation, rather more specifically as an impure and infectious ideology and culture. Pesach is not merely about Hashem’s sheltering us from their oppression, but about our purging from their infection. Indeed, though the Egyptian Exile obviously was externally manifest in subjugation to Pharaoh, it was more fundamentally marked by our spiritual subjugation to the Evil Inclination. There is a reason why Rav13 insists that obligation of relating the story of Yetzias Mitzrayim begins with “M’Techilah Ovdei Avodah Zarah Hayu Avoseinu”-”Originally, our forefathers were worshippers of foreign deities,”14 and that is because our fundamental subjugation was to the spiritual filth which Ancient Egypt represented. Without internal purification from that filth, an external shelter would have been pointless.

The undeserved lovingkindness Hashem had done for us then, despite our nakedness of merit and our spiritual filth, necessarily demanded a sacrifice on our part. We were sheltered from the outside society during the final plague against Egypt so that we could ultimately engage in a process of purification from the inside out, beginning with the Korban Pesach. After all, how can we expect Hashem to continue working His magic for us if we refuse to take that step forward for Him? Though He acted for us then, it came with a price: “Ba’avur Zeh Asah Hashem Li”-“For the sake of this (Avodah) Hashem acted for me.”15

Answering the Ka’Eileh Challenge

Based on all of the above, perhaps we could suggest that while Chag HaSuccos and its Korbanos emphasize the external differentiation between the B’nei Yisrael and the nations of the world, as manifest by the diminishing Parei HaChag, Chag HaMatzos and its Korban Musaf communicate the need for our conditioning of that purer life style—how we must put the Avodah into practice which separates us internally from the nations. And as was said, the necessary separation and the shelter which concretizes that separation are not generated over night. Indeed, the conditioning must be constant.

As far as Chag HaMatzos is concerned, we need at least a week. We cannot even conceive of a building a protective exterior structure until we have spent a week consuming the Matzah and purging ourselves from the “Chameitz” within. In this vein perhaps, we can explain why the Musaf remains the same each of those seven days. Just as we offer a regular, consistent Elevation offering, the Olas HaTamid—day in and day out—for Chag HaMatzos, we need drill in a practice whose spiritual impact will remain with us consistently and constantly. Day in and day out on Pesach, we deliver offerings exactly “Ka’Eileh”-“like these” until, indeed, it does.

May we all be Zocheh to once again offer the Musafim of Chag HaMatzos—“Ka’Eileh” for all seven days—as well as the Musafim of all the appointed times throughout the year, and be impacted by the spiritual energy each one offers with the rebuilding of the Beis HaMikdash and the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a wonderful Pesach and Chag Kasher V’Samei’ach! (If you would like a PDF file of my freshly edited Haggadah, please let me know!)

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bamidbar 28:16-25

- 28:23-24

- Sifrei 147

- Bamidbar 29:12-34

- See Shemos 12-13 and Vayikra 23:43

- See Succah 27A

- Shemos 12:1

- See Succah 2A

- Vayikra 23:43

- Brachos 17A

- See Rashi’s comments there

- To 29:11-12 citing Succah 55B

- Pesachim 116A

- Which introduces the text of Yehoshua 24:2-4

- Shemos 13:8