| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben Yosef A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -MY BROTHER: MENACHEM MENDEL SHLOMO BEN CHAYA ROCHEL -HaRav Gedalia Dov Ben Perel -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Yechiel Baruch HaLevi Ben Liba Gittel -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -And all of the Cholei Yisrael, especially those suffering from COVID-19. -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

חֻקַּת-בָּלָק ● Chukas-Balak

● What might be the unifying connection between Chukas and Balak? ●

“The Voice of Bitachon & the Hand of Hishtadlus”

The “double-Parsha” of Chukas-Balak is the rarest combination of Sidros that can be read on a single Shabbos as it is only read in the Disapora when the second day of Shavuos falls out on Shabbos, putting the B’nei Yisrael of the Diaspora a Sidrah behind those in Eretz Yisrael. With that said, the doubling of these Sidros can be passed off as a “fluke” of sorts. They are two very different Sidros which have little to do with one another directly. Chukas focuses on the continued journeys of Israel through the wilderness and Balak tells us of a completely separate discussion, the plots of our enemies.

However, upon further investigation, one might notice a couple of noteworthy links between Chukas and Balak which are quite fundamental. These links, if not mere coincidences, are telling of some hidden but important lessons.

The Bridge between Chukas and Balak

Before we investigate internal and thematic connections between the two Sidros, some basic background is in order. Between most Sidros in the Torah, “double-Parsha” or not, some simple, contextual link can be typically be identified. The simple link between Chukas and Balak is the B’nei Yisrael’s “reign of terror” over the surrounding nations which worried Balak, king of Moav. This dominance of the B’nei Yisrael is recorded in the latter end of Chukas.1

More specifically, the Chumash sets up the narrative for Parshas Balak quite directly by elaborating on the geography of the B’nei Yisrael’s travels as a backdrop for their wars against Sichon of Emori and Og of Bashan. In Chukas, the Torah reveals that Emori and Bashan are separated from Moav by the land of Arnon where the B’nei Yisrael stood after their wars with the two kings. And just before Chukas meets its close, the Chumash relates that the B’nei Yisrael parked themselves at the border of Moav, completing that stage for Parshas Balak.

The Most “Striking” Connection

Now, as was mentioned, the above is only a basic connection between Chukas and Balak. With that information, the line between Chukas and Balak is only as thin as the line between one chapter and the next in any given book. However, there are apparently some hidden, internal connections between Chukas and Balak.

In the most prominent narrative of either Sidrah, we find a major prophet defying the will of G-d and using a staff or rod to strike something multiple times, out of confusion and seeming frustration. Both of these individuals were rebuked for doing so. Who are these individuals?

In Parshas Chukas, the “culprit” is none other than the greatest man in history, let alone, the greatest prophet of the B’nei Yisrael, Moshe Rabbeinu at the scene of Mei Merivah.2 There, he infamously hit the rock twice to retrieve water from it rather than merely speaking to it as he was commanded. G-d would rebuke Moshe for failing to sanctify His Name before the nation and would forbid him from completing his mission of leading the B’nei Yisrael into the Promised Land.

On the opposite extreme, in Parshas Balak3, we have the wicked Bil’am, apparently one of the greatest enemies of the B’nei Yisrael and possibly the greatest prophet of the gentiles. And despite G-d’s initial ban against Bil’am setting out to curse the B’nei Yisrael, Bil’am negotiated and received permission to approach the B’nei Yisrael. However, he was stopped on the road by an unseen angel. His she-donkey who could see the angel stopped whereupon Bil’am angrily struck her, a sequence that repeated two more times thereafter. Both the she-donkey and the angel would rebuke Bil’am for hitting her those three times. Ironically, the angel would then permit Bil’am to attempt to complete his mission of cursing the B’nei Yisrael, only so that Hashem could reverse Bil’am’s efforts by turning Bil’am’s curses to blessings.

Now, as we will see, the connections between Chukas and Balak go far deeper than mere striking. But, before we get to those deeper connections, there is apparently one more piece to our puzzle.

The “Kuf-Peih” Triad

The final piece to the apparent puzzle of Chukas and Balak is another whole Sidrah, namely Parshas Korach. We find two mysterious variables that Korach shares with both Chukas and Balak, the first is the “Kuf” and the second is the “Peih.” What exactly does that mean?

- The “Kuf” Factor [ק]

If one looks at the titles of these three successive Sidros, one might notice that they are each made up of three-letter words, and the letter they share in common is the letter “Kuf” [ק]. In Korach, the “Kuf” appears in the beginning of the word [קרח], in Chukas, it appears in the middle of the word [חקת], and in Balak, it appears in the end [בלק]. Why and how this pattern might be significant requires further discussion, but that is the layout for the “Kuf” factor.

- The “Peih” Factor [פה]

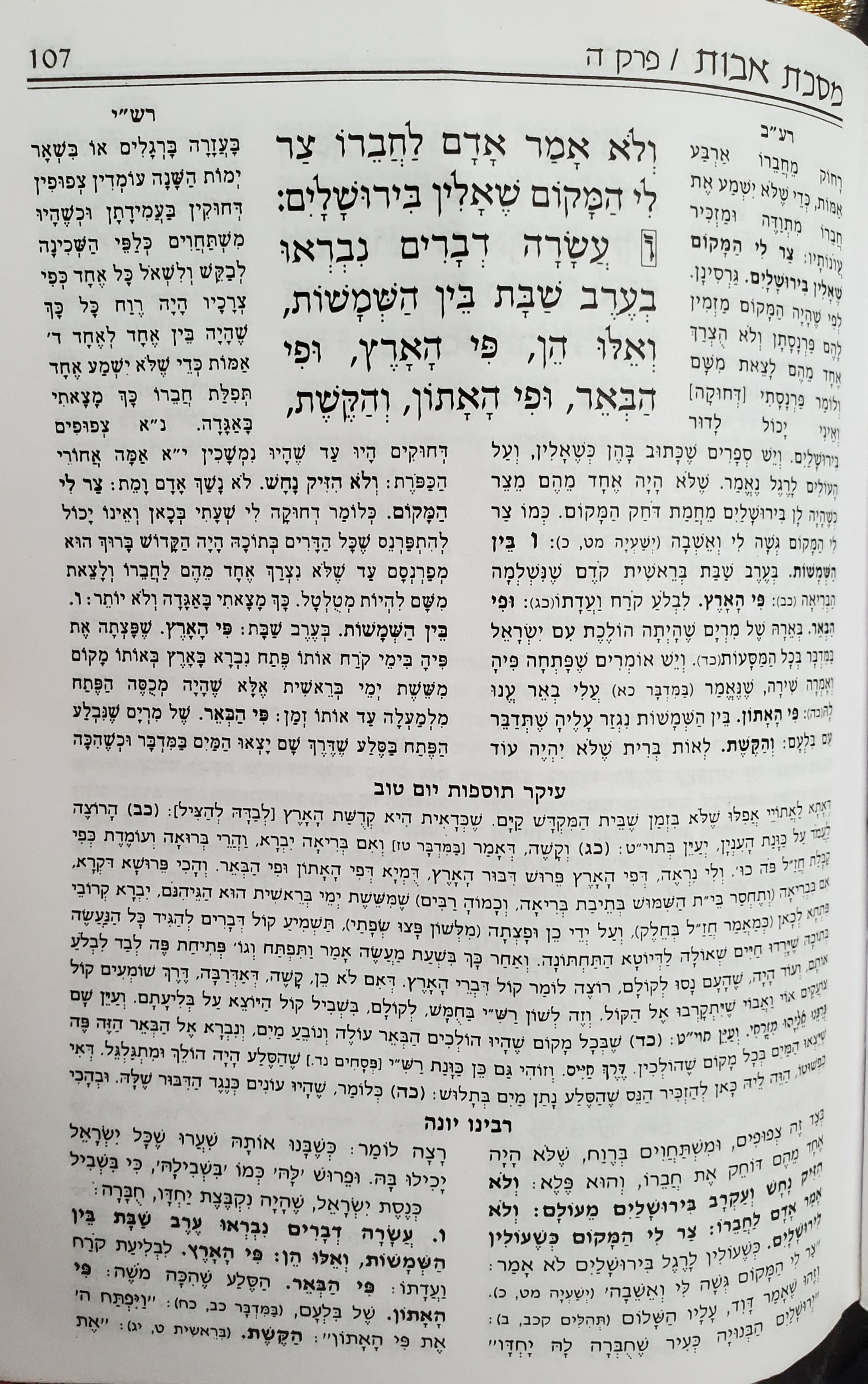

What is the “Peih” factor? For this one, we need the help of Chazal. The “Peih” factor, as we’ve referred to it, has less to do with the Hebrew letter “Peih” [פ], but more to do with what the word itself actually means. The word “Peih” (or “Peh” [פה]) means “mouth,” and Chazal teach us in Pirkei Avos quite fascinatingly that at twilight on the Sixth Day of Creation, Hashem created three supernatural “mouths,”4 all of which appear successively in our three Sidros, Korach, Chukas, Balak. These three mouths are (1) the “Pi HaAretz”-“mouth of the earth” which swallowed Korach alive, (2) the “Pi HaBe’eir”-“mouth of the well” which hydrated the B’nei Yisrael in the desert in Miriam’s merit and which Moshe re-dug, and finally, (3) the “Pi HaAson”-“mouth of the she-donkey” which told Bil’am off.

These connections are certainly intriguing, but what exactly is their significance? What is the underlying meaning behind these apparent links of the letter “Kuf” which shifts places between the titles of these Sidros and the recurring, supernatural “mouths” that appears in each?

The Gliding “Kuf” and the Three Mouths

The “Kuf” factor is obscure, and as such, interpreting its significance in our contexts is naturally challenging as there may be layers upon layers of hidden significance to it. Accordingly, we are going to spend less time speculating this factor, though we will cite a couple of insights later in our travels. However, in the meantime, we will have to explore the meaning of the three “mouths” identified by Chazal. These mouths will be the backdrop for not only some possible conclusions for the “Kuf” factor, but the hidden message that is being conveyed between Korach, Chukas and Balak.

What was the purpose of the three mouths that were created at twilight before the first weekend of Creation? Is there a unifying theme that they share?

In order to answer the question revolving around the “Peih” factor, let us consider what the point of a mouth is in general. The mouth, as we know it, serves two apparently opposite functions. Those two actions are (1) eating, a physical act which involves taking in material substance to service the body, and (2) speaking, an intellectual and spiritual exercise which entails converting and processing thoughts into intelligent speech, to be discharged to listeners outside oneself for the purposes of communicating messages to others. One is fundamentally selfish while the other involves interpersonal communication. One function of the mouth takes in while the other gives forth. One is physical and natural to all living creatures while the other is intellectual and unique to humans alone.

Now, the question is which of these two functions of the mouth is highlighted in the three “mouths” of Korach, Chukas, and Balak?

The Secret Utility

If one thinks about it, between the mouth of the well, the mouth of the earth, and the mouth of the she-donkey, each one served to teach a profound lesson about the gift and power of speech, the second function of the mouth that is unique to humans. It is this second, spiritual function of the mouth that is the mouth’s primary function, as far as humans are concerned. It is in this vein that Onkelus famously interpreted the “Nefesh Chayah”5 which Hashem imbued in man as a “Ruach M’malela,” literally a “speaking spirit.”

Now, although this spiritual gift was imbued in all of mankind, only one family would inherit this gift so as to call this gift its own craft. It is in this vein that Yitzchak differentiated between his two sons, Yaakov and Eisav. Yaakov is defined by his gift of speech, “HaKol Kol Yaakov”-“The voice is the voice of Yaakov,”6 whereas Eisav is defined by external actions, “V’HaYadayim Yidei Eisav”-“And the hands are hands of Eisav.”6 What exactly the deeper meaning of this dichotomy is, we will have to eventually investigate. But, suffice it say for now, this dichotomy will explain the curious relationship between our Sidros.

With that, let us return to the “mouths” of the “Kuf-Peih” triad, Korach, Chukas, and Balak. What exactly are they saying to us?

- Korach & the Mouth of the Earth

Beginning with Parshas Korach, we have discussed in the past how Korach had taken full advantage of the art of speech to debate and defy Moshe Rabbeinu, turning even national leaders against him. Simply put, he spoke way out of turn. And since he tried to deny Moshe, Hashem opened the “mouth” of the earth to quash Korach’s rebellion and silence Moshe’s doubters, testifying that Moshe had no agenda, but that he was Hashem’s “mouthpiece” as it were.

But if we think about the nature of the divine response to Korach’s words, we might be astonished when we reconsider the function which the “mouth” served in that account. Indeed, although the earth certainly produced invaluable testimony that day, practically speaking, the earth’s mouth opened, not to deliver any wise words, but to swallow Korach alive. Thus, the way in which the earth was “animated” seems to resemble the former function of the mouth, selfish eating.

Why would G-d respond to Korach’s intelligent speech with a mouth of “consumption”? Perhaps Hashem utilized the selfish function of the mouth to expose the true selfishness hiding beneath Korach’s seemingly wise words. Though one could have argued to the nobility of Korach’s campaign, Hashem revealed that it was never about the principle, but about his personal greed. Apparently, there may not have been anything intrinsically wrong with the speech itself. Perhaps Hashem would have welcomed a healthy and earnest discussion about differing ideals; perhaps there could have even existed multiple truths to the matter. It was the rebellious agenda behind Korach’s speech which could not be tolerated.

- Moshe & the Mouth of the Well

In Parshas Chukas as well, we have a mouth which did not directly speak any words. In fact, it was the inactivity of mouths in this story which spoke the greatest of volumes. To simplify a story that is not simple at all, while Moshe Rabbeinu was himself charged to speak to the rock to extract water from it for the B’nei Yisrael, for some reason or another, he resorted to striking it. Though Moshe forced the rock’s mouth open manually, the same mouth would have miraculously opened itself had Moshe only spoken to it.

Unlike Korach’s sin, Moshe’s was highlighted by his neglect of appropriate speech. Though he did not act out of selfishness as did Korach, Moshe abandoned the divine function of speech altogether when he quite literally took matters into his own hands. We will return to Moshe’s actions as they will be significant once we’ve seen the final “mouth” in Parshas Balak.

- Bil’am & the Mouth of the She-Donkey

In yet another lesson revolving around speech, Parshas Balak brings us the mouth of Bil’am’s she-donkey which miraculously opened to rebuke Bil’am for striking her. Here, an animal was miraculously gifted with humanly intelligible speech, a phenomenon which we have not found concerning the other “mouths.” With this final mouth, Hashem taught Bil’am that despite his own human intelligence, he would have no control over the gift of speech. G-d could and would later manipulate Bil’am’s speech using him, like the donkey, as a puppet to communicate His own desired messages.

The irony in this story is that Bil’am was determined to verbally curse the B’nei Yisrael, yet he apparently needed to resort to physical violence when addressing his donkey. As foolish as Bil’am might have actually been, was there any method whatsoever to his madness? Is there a reason why he sought to use speech of all things against the B’nei Yisrael? Apparently, Bil’am was well aware of the fact that speech was the secret craft of the B’nei Yisrael, the descendents of Yaakov Avinu. Thus, Chazal inform us of his measure for measure punishment, that as Bil’am attempted to use Israel’s craft against them, his own craft—that of Israel’s enemy nations—would be used against him, thus Bil’am fell to the sword, the extension of the hand of Eisav.7

Indeed, this is not the first instance when Israel’s enemies devised a battle strategy against them with Israel’s secret utility in mind. In our very own Parshas Chukas, Rashi8 suggests that Eisav’s descendants of Amaleik disguised themselves as Cana’anites to thwart the precision of Israel’s prayers. Earlier in the same Sidrah, Rashi cites yet another tradition containing a subtextual conversation that took place between the B’nei Yisrael and none other than Eisav’s other descendants of Edom.9 During Israel’s negotiations with its Edomite cousins as the nation requested the right of passage through their land, Israel described their Exodus from Egypt, how Hashem had heard their voice which, Rashi reminds us there, is the craft of Yaakov Avinu. The brazen response from Edom was a direct challenge that even if Israel would pride itself over its craft of speech, Edom would still use its own craft of Eisav and extend its sword against Israel should Israel attempt to pass through its land. The theme, once again, is that of intelligent speech versus external action, the voice of prayer versus the hand of war.

Voice vs. Hands

The question is what exactly is the nature of this dichotomy between the voice and the hands? Is it as simple as a battle of good versus evil? Is it a matter of “our craft” versus “their craft”? Perhaps a cursory glance at our sources might lead one to the conclusion that, yes, Moshe’s mistake was manifest in his abandonment of the craft of Yaakov and his resorting to the craft of Eisav, and that similarly, Bil’am’s mistake was his attempt to exploit Israel’s craft against it. With deeper investigation though, we will see that that is not true at all. There are apparently places for action, where the hand must be utilized, even by a Ben Yisrael.

The Place for Action

Consider how when the B’nei Yisrael were trapped between the Egyptian army and the Yam Suf, when Moshe raised his voice in prayer, Hashem stopped him as, apparently, it was not a moment for prayer, but for action.10 And yet, later in the very same Sidrah, during Israel’s hands-on war with Amaleik, Moshe actually suspended his own hands in the air, signaling the B’nei Yisrael to direct their hearts and trust upward to Hashem.11 At that point, the craft of the hands was secondary.

What is apparent is though is that although the voice is the natural craft of Yaakov Avinu which he bequeathed to the B’nei Yisrael, there is a time and place for the handiwork of Eisav. This much is perhaps symbolized in the fact that although Yaakov would not mask his own voice when speaking to his father, nonetheless, by his mother’s orders, he wore the “hands of Eisav” on his sleeves.

The “Kuf” Factor – Action or Voice?

In the same vein, it could be that our mysterious letter “Kuf” is simultaneously symbolic of both the crafts of the voice and the hand.

On the one hand, Chazal teach us that the letter “Kuf” stands for “Kadosh” [קדוש] or “Holy” representing the Holy One Blessed is He.12 Obviously, in this case, the “Kuf” can symbolize of the most sublime and spiritual Being. And yet, Zohar reveals additional symbolism to the “Kuf” which has seemingly opposite connotations; for example, the word “Kuf” [קוף] translated straight means “monkey,” something which has the guise of a human, but without intelligent speech. In this vein, the Lubavitcher Rebbe suggested that the very name Amaleik is contraction of the words “Ameil Kof” [ק׳ עמל or קוף עמל] literally, “toil of the monkey.”13

Moreover, the same letter apparently also represents the “Kelipah” [קליפה], the term in Kabbalah which describes the unholy, negative forces that mask the sparks of holiness in this world.

And yet, back at the opposite extreme, the same letter is the first letter of the word “Kol,” [קול] used twice in reference to Yaakov Avinu, “HaKol Kol Yaakov”-“the voice is the voice of Yaakov.”6

If all of the above is true, then what exactly is the essential difference between two crafts? When is either appropriate or inappropriate?

The Voice of Bitachon & the Hands of Hishtadlus

Granted, although we have been able to ascribe an “owner” to each craft, that of the voice and that of the hands, we have also been able to identify instances where each craft was appropriate. If we could simplify the deeper significance of these crafts, we might suggest that the “voice,” of prayer for example, represents Bitachon or trust, whereas the hands of action represent Hishtadlus, human effort. Even outside the context of prayer, one who merely uses words instead of resorting to aggression and violence demonstrates trust in the interpersonal relationships which relies on the ability to communicate in a civil way to reach a desired result. On the other hand, there are times where one simply cannot just trust the world around him or even his own prayers alone to reach his desired result, times when he must engage in personal effort. Yes, Israel’s craft is that of the voice because only G-d assures our successes, but that does not mean that Hishtadlus is never required.

With this information, perhaps we can begin to appreciate how venturing into the sea was a time for Hishtadlus or action on the part of the B’nei Yisrael who perhaps lacked merit to back their prayers. And yet, warring with Amaleik was a circumstance where absolute Bitachon was undoubtedly in order; without it, the war effort would prove futile.

Returning to the main narratives of Chukas and Balak, Moshe’s story highlights the catastrophe of speech neglected and inappropriately exchanged for the craft of the hands. It was an occasion where Moshe needed to teach the B’nei Yisrael a lesson in faith.

On the other hand, Bil’am’s story highlights the attempted misuse of speech and the dependence of the power of speech on the will of G-d. Since the craft of speech is founded on Bitachon in G-d, it could not possibly be manipulated and utilized as a tool against G-d’s righteous people. The attempt to do so is a misunderstanding of what the power of the speech truly is. Parenthetically, that might explain why, by design, praying to Hashem does not always “work” if the goal is to “get you what you want.” Prayer is not black magic as Bil’am thought it was. G-d can’t simply be manipulated. The voice of prayer relies on trust in G-d’s capability and will to either grant or withhold whatever it is we want. This kind of faith accepts that G-d might indeed turn us down.

Balancing Bitachon & Hishtadlus

In the end, it is not always clear which craft is necessary for each of life’s circumstances. We don’t know how much Hishtadlus needs to to be incorporated in a given a task, or even how much we can reasonably rely on Bitachon in the absence of personal merit. Accordingly, the only appropriate approach is to generate that much needed balance between the voice of Bitachon and the hands of Hishtadlus.

May we all be Zocheh to “strike” that balance between voice and hand, between Bitachon and Hishtadlus, and Hashem should not only enable us to be successful in our individual and collective mission in fulfillment of Ratzon Hashem, but answer our efforts and trust in Him with victory and deliverance from our enemies forever with coming of the Geulah in the days of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bamidbar 21

- Bamidbar 20

- Bamidbar 22

- Pirkei Avos 5:6

- Bereishis 2:7

- 27:22

- See Rashi to Bamidbar 22:23 citing Tancuma 6 based on Bamidbar 31:8 [See Rashi’s comments there as well], and Bereishis 27:40.

- See Rashi to Bamidbar 21:1 citing Tanchuma 18.

- See Rashi to Bamidbar 20:16 and 20:18 citing Tanchuma, Beshalach 9.

- See Rashi to Shemos 14:15 citing Mechilta and Shemos Rabbah 21:8.

- See Rashi to Shemos 17:11 citing Rosh HaShannah 3:8 and 29A.

- Shabbos 104A

- Ohr HaTorah, Vayikra 1