This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta

-Miriam Liba Bas Devora

-Aharon Ben Fruma

-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamah of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus.

בס”ד

שְׁלַח ~ Shelach

“Yehoshua & Caleiv or Caleiv & Yehoshua”

Numbers.13.16

Numbers.13.30

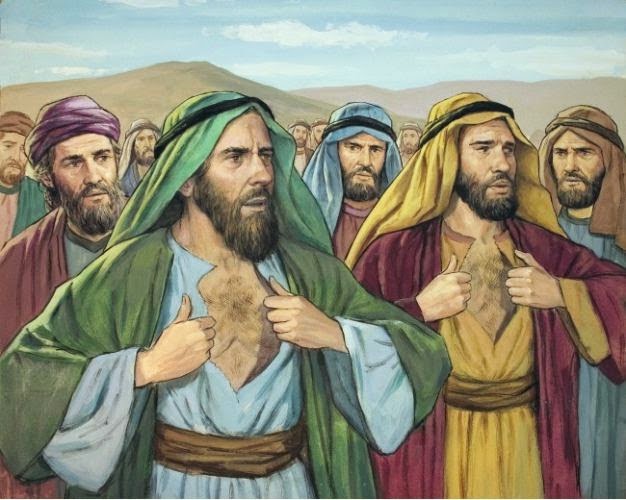

Numbers.14.6

Numbers.14.24

Numbers.14.30

Numbers.14.38

Parshas Shelach primarily focuses on the story of the Cheit HaMiraglim, the Sin of the Spies [B’Midbar 13-14]. After the spies came back with their negative report of the “situation” in the Promised Land, it took two heroes among them, Caleiv and Yehoshua, to speak up on behalf of Hashem’s land and remind the B’nei Yisrael of their destiny to conquer it. Of course, the damage of the Miraglim had already been done as the nation panicked and attempted to return to Egypt. Thus, the entire generation would henceforth be disqualified from their rights to entering the Promised Land and the Miraglim would be sentenced to an immediate death by a gruesome plague. Nonetheless, Yehoshua and Caleiv would be recognized and rewarded for their resistance, in that they would be the only two individuals of the generation who would ultimately enter and inherit a portion of the Promised Land.

But, when looking at the two heroes of our story, one cannot ignore the obvious difference between them in terms of their volume or “loudness.” Initially, after the Miraglim have stated their piece, making their case against Hashem’s instructions that they enter the land, Caleiv alone stands up and protests [13:30]. True, afterwards, Yehoshua and Caleiv, together, protest the report of the Miraglim, and they express their disapproval and grief by tearing their clothes [14:6], however, the verbal protest seems to have begun with Caleiv.

This pattern apparently repeats itself when Hashem is condemning the nation and giving the heroes their credit. There, one might’ve noticed that Hashem initially only acknowledges Caleiv’s heroic opposition to the Miraglim, singling out Caleiv alone as the one who earned his rights to enter the land, ignoring Yehoshua [14:24]. True, Yehoshua supported Caleiv’s cause verbally later, and as such, later in His speech, Hashem does mention Yehoshua as well at least twice, saying that Yehoshua and Caleiv would enter the Promised Land [14:30, 38]. However, at the beginning of that speech, the relatively quieter Yehoshua at least seems to go unnoticed.

What’s more is that Caleiv is acknowledged uniquely for having a “Ruach Acheres”-“another spirit” [14:24]—that he was literally “something else.” Rashi [citing Tanchuma, Shelach 10] explains this expression to mean that Caleiv had two spirits, one which was conveyed through his mouth, and one concealed in his heart, as he told the other spies that he would join their “scheme,” yet, in his heart he intended to later speak the truth, thereby enabling him to silence them later. It could be that according to the simple explanation, Caleiv had this spirit or this natural ability which enabled him to outwardly stand up to the Miraglim and not be sucked into their counsel. In this vein, Rashi [to 13:22 citing Sotah 34B] says that Caleiv actually separated himself from the Miraglim during their journey by going to Chevron to pray at the gravesite of the Avos (forefathers) that he not be enticed by his colleagues.

The glaring omission of Yehoshua, in this praise, seems to imply that Yehoshua apparently did not have this same unique spirit. While he might have, on his own, been able to recognize the truth, perhaps, in his personal meekness, Yehoshua might’ve been on impressed upon by the majority of the Miraglim, because, indeed, like Moshe Rabbeinu, Yehoshua was exceedingly humble. The idea that Yehoshua was “at risk” is evident from the fact that Moshe actually needed to add a letter to Yehoshua’s name, changing it from the original name Hoshei’a, as a form of prayer that, in the event that the Miraglim fail, Yehoshua should be “saved” from “their counsel” [Rashi to 13:16 citing Sotah 34B] (as the name Yehoshua is a compound of the phrase “Kah Yoshiacha”-“May G-d save you”).

So, from the larger story, while there are clearly two heroes in the story, if we can point to one main hero, it seems that we would undoubtedly point to Caleiv. He was not just the voice of reason, but he was the voice period. He was vehemently outspoken, quick to silence the sinners who outnumbered him and say that “This is wrong!” Of course, Yehoshua was a righteous man and also stood against the numbers, joining Caleiv in the less popular position, and he certainly deserves credit, which indeed, he receives. However, Yehoshua appears to be more of the sidekick, at the end of the day. Or does he…?

Although Caleiv is the voice of the resistance against the Miraglim, Yehoshua is ultimately the one who ends up succeeding Moshe Rabbeinu and leading the next generation of the B’nei Yisrael into the land. Yehoshua was Moshe’s top disciple. If Caleiv was apparently greater though, perhaps he should’ve succeeded Moshe. Apparently, Caleiv wasn’t entirely greater then…

Beyond that, even in our story, although Caleiv receives more explicit acknowledgment, if one looks at the text closely, as subtle as it is, there are times where Yehoshua actually seems to supersede Caleiv. Take a look at every time that the two names are mentioned together. You will notice that sometimes, Caleiv’s name is mentioned first, and yet sometimes, Yehoshua’s name is mentioned first.

When they tear their clothes and try to reason with the nation [14:6], Yehoshua’s name is mentioned before Caleiv’s. Yet, when Hashem singles them out from the B’nei Yisrael as the only people who would enter the land [14:30], Caleiv is before Yehoshua. And then, when Hashem contrasts them from the other Miralgim who would die instantly in a plague [14:38], Yehoshua’s name comes before Caleiv’s again.

Now, while we can have a separate analysis to explain, based on context, why the order of their names varies within the story, the fact is that, at least in our story here, more often than not, when they’re listed as a pair, Yehoshua’s name actually comes before Caleiv’s! So, yes, at first, Caleiv alone silenced the crowd, and yes, at first, Caleiv alone was singled out by Hashem, however, in this more subtle sort of way, the text, at the same time, seems to hint at the superiority of Yehoshua. So, what are we to make these differences between Caleiv and Yehoshua, or perhaps Yehoshua and Caleiv? Who is the “real hero” at the end of the day?

At the risk of suggesting what will come off as a cliché, copout answer, perhaps we might start with a well-known idea suggested back in Sefer Shemos regarding why sometimes in the Torah, Moshe’s name precedes Aharon’s, yet at others, Aharon’s name precedes Moshe’s. There, Rashi [to Shemos 6:26 citing Mechilta 7:1] explains that by switching the order now and then, the Torah implies that really, Moshe and Aharon were “equal” in spiritual stature. The obvious problem with this explanation is that Moshe was clearly greater than Aharon, at least in the sense that he, over his older brother, became the leader of the entire B’nei Yisrael and the greatest prophet who ever lived. And as for this question, the answer suggested by many is that although comparatively, Moshe was greater, each Moshe and Aharon in their own way were equal in terms of their individual spiritual achievement. For their respective gages or scales, they each maximized their potential.

But again, to actually compare Moshe and Aharon against each other is a futile cause considering that their spiritual missions and potentials were not the same. Moshe was the leading prophet of the nation, yet Aharon was the High Priest.

Perhaps, in this way, Yehoshua and Caleiv can be likened to Moshe and Aharon. The question we have to answer, then, is what the difference was between the respective spiritual missions of Caleiv and Yehoshua.

For this, we have to look into the respective roots of both Yehoshua and Caleiv. Caleiv was a descendant of Yehudah, while Yehoshua was a descendant of Yosef. These two names represent to giant legacies, a clash of personalities. The two names together symbolize the tradeoff between two royal, spiritual dynasties, which, at a point, obviously did not get along.

Back in Sefer Bereishis [Ch. 37], Yaakov Avinu’s children were in a bitter feud surrounding the issues of favoritism, firstborn rights, dominance, royalty and many other details. Of course, the Yosef was the favorite son, yet Yaakov’s sons from Leah hated Yosef. Yosef’s brothers ultimately have him kidnapped and sold to Egypt, yet Yosef ultimately proved his righteousness by overcoming enticement from his master’s wife, and he was later elevated to the Egyptian throne. And yet, among his brothers, Yehudah, who initiated the sale of Yosef ultimately rose to the occasion, taking responsibility not only for his actions with his daughter-in-law Tamar, but for Yaakov’s “interim favorite son” Binyamin. As a result, Yehudah would merit bearing the kings of the B’nei Yisrael generations later. These are the legacies of Yehudah and Yosef.

Now, while both Yosef and Yehudah ultimately proved themselves to be heroes, much like in the story of the Cheit HaMiraglim, the damage had been done, and as a result of the feud, their generation remained in Egypt, and their descendants would suffer the Egyptian Exile and subjugation.

Consider this: Finally, after experiencing Yetzias Mitzrayim, the Exodus from Egypt, and the B’nei Yisrael are on their way back to the Promised Land of their forefathers, the Miraglim come along and arouse national chaos which results in an attempt to turn around and go back to Egypt. That means that essentially, the Miraglim were about to undo the Exodus from Egypt.

So, if the Miraglim’s report essentially threatened to undo Yetzias Mitzrayim, Yehoshua and Caleiv’s respective responses would have to counter that attempt and keep the nation from going back. But in order to keep the nation from falling back into the Egyptian Exile, one has to understand what triggered the Egyptian Exile in the first place. And by now, we know that the Egyptian Exile can be traced back to the feud between Yosef and his brothers. But, what does this feud have to do with the respective actions of Caleiv and Yehoshua? A lot.

In the original feud between the brothers, nobody was blameless. Yosef, many would say, was the instigator, as he would bring negative reports about his brothers to their father, and while some of his allegations were accurate, many were not. By being too outspoken, and some would even say slightly haughty, Yosef was in the wrong. Yet, the more obvious culprit in the feud was the brothers, but particularly Yehudah, who decided to have Yosef sold away, to feign Yosef’s death, and then to take zero responsibility for it. Thus, in exceedingly simplified terms, Yosef’s loudness and Yehudah’s quietness played a role in causing the Egyptian Exile. It was when Yosef mellowed and humbled himself that he rose up. Similarly, it was when Yehudah spoke up and took responsibility that he rose up.

Fast-forward to the Cheit HaMiraglim, where the sin comes about, much like the feud between Yosef and his brothers, through “negative reports” (“Dibah Ra’ah,” the same term used to describe Yosef’s allegations against his brothers). Who would become the heroes of the day to counteract these reports other than Caleiv and Yehoshua? Yet, each of them in his own necessary way, acted according to the spiritual mission that each one inherited from his predecessor.

If Yehudah’s original problem was a lack of voice and responsibility, Caleiv now spoke up when no one else would, as Yehudah ultimately did, to lead the revolution against the injustice. And if Yosef’s original problem was his grandeur and loudness, Yehoshua would need to be humble, specifically not speak up, but follow Caleiv’s righteous lead, and allow his actions to speak louder than his words.

Coming full circle, whether “Caleiv and Yehoshua” or “Yehoshua and Caleiv,” both were monumentally important heroes in this story, each in his own virtuous way, each fulfilling his spiritual role. It’s often not easy to recognize our inherent mission as individuals, but it takes a lot of introspection and self-awareness for us to become the heroes of our own story. We have to assess our situation and our actual selves, investigating our weaknesses, tendencies, and the needs of the moment, and if we do and act accordingly, we too will rise to the occasion.

May we all be Zocheh to know when we need to speak up and take responsibility, when to quiet down and humble ourselves, act accordingly so that we can overcome the challenges of our lives, maximize our spiritual potentials, and follow the lead of Caleiv and Yehoshua back to Eretz Yisrael with the coming of the Geulah in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Josh, Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂