This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H & my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H & in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta, and my great aunt Rivkah Bas Etta

-Miriam Liba Bas Devora

-Yechiel Baruch HaLevi Ben Liba Gittel

-Aharon Ben Fruma

-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamah of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus.

בס”ד

תְּרוּמָה ~ Terumah

“Do You Wanna Build a Mishkan?”

Exodus.25.2

Exodus.25.8

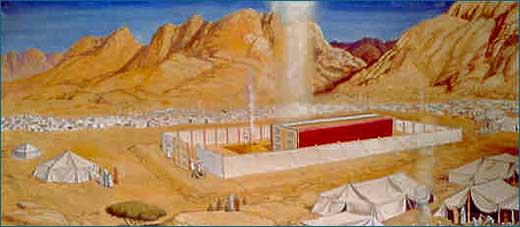

Parshas Terumah officially begins the Torah’s “Mishkan Series”—all of the chapters pertaining to the construction of the Mishkan (Tabernacle) which will take us to the end of Sefer Shemos. However one understands the purpose of the Mishkan, whether it represented Hashem’s physical, mobile home on earth, whether it was meant to atone for the Cheit HaEigel (Sin of the [Golden] Calf) as Rashi explains in line with Chazzal [Midrash Tanchuma 2, 8; See Rashi to 38:21], or whether it was meant to recreate either the Divine experience of Har Sinai or the universe in a microcosm as the Ramban explains, the Mishkan was a communal project that was incumbent on all of the B’nei Yisrael. As we continue to long for the rebuilding of the Mikdash (Temple) in our lifetime, seemingly no one would argue that the concept of a Mishkan or a Mikdash is not an absolutely necessary facet which the B’nei Yisrael needs for its service of Hashem.

If the above is true, then the way the Torah presents “command” for the nation to begin the Mishkan project might be somewhat troubling. Hashem says [Shemos 25:2] “…V’Yikchu Li Terumah Mei’eis Kal Ish Asheir Yidvenu Libo Tikchu Es Terumasi”-“…and they shall take for Me a Terumah; from every man whose heart inspires him shall you shall take My Terumah [elevated portion].”

Rashi explains that the phrase, “Kal Ish Asheir Yidvenu Libo”-“every man whose heart inspires [motivates] him” means that one is to give the offering with Ratzon Tov, a sense of good will, as a present. The word “Yidvenu” comes from the word “Nedavah,” which means a gift, and accordingly, has connotations of something that is voluntary, optional, not mandatory or at all required by the letter of the law. Do we need any more synonyms? The point is that the raw materials for the Mishkan, apparently, were meant to be taken from a purely voluntary contribution.

If that’s the case, the problem is as follows: The building of the Mishkan, as we’ve understood it, is a Tzivui, or a command, from Hashem. Indeed, the building of the Mishkan is considered its own Mitzvah (commandment); “V’Asu Li Mikdash V’Shachanti Besocham”-“And they shall make for me a Temple and I shall dwell among them” [25:8]. In other words, “Do it”—it is a command. That should logically imply that the Mishkan project was mandatory. If so, then how can it also be simultaneously voluntary? Can it possibly be both optional and required? Is that not a contradiction?

Aside from the apparent paradox, didn’t we argue that the Mishkan was absolutely necessary? How then could the means for this absolutely necessary project be at all subject to the peoples’ personal discretions? If the Mishkan project was actually voluntary, then it sounds as though, if, in theory, there were no donors—if the people had been unwilling to voluntarily give to the cause, then there would simply have been no Mishkan. Would that have been the case? We argued that it was G-d’s home and the center of our Avodah—we need it. So, is the contribution to the Mishkan project something mandatory (Tzivui) or voluntary (Nedavah)?

Additionally, assuming that it is possible for the Mishkan project to be both mandatory and voluntary, why, in any event, would Hashem specify here, of all places, that the contribution be given voluntarily? Does the Torah do this elsewhere? Hashem doesn’t say that “every man whose heart inspires him shall put on Tefillin” or that “every man whose heart inspires him shall keep Shabbos.” He simply commands us, “Do it.” “Put on Tefillin.” “Keep Shabbos.” Why, all of a sudden, does Hashem soften and allow us to essentially do what we want when it comes to the Mishkan?

There may be various ways to understand the seeming paradox in the nature of the Mishkan project (and I personally have addressed this very question elsewhere), but perhaps the simplest answer one could suggest is that there is absolutely no contradiction between the “command” to build a Mishkan and the “request” for “voluntary” contributions, because the command or mandatory requirement to build a Mishkan was addressed to the people as a collective—as a community—while the request for voluntary contributions was addressed to the individual members of the nation. In other words, the community was commanded to build a Mishkan, while individuals are being asked to contribute what they can to the cause. Did the Mishkan have to be built? Yes. But, how to get there—where to get the materials from, how much each person would give, if a given individual would even give at all—is all up to the motivation and discretion of each respective individual.

Now, the paradox is resolved. Fine. But, still, considering how necessary the Mishkan was, how could the Mishkan contributions have been at all voluntary—even for the individual? Could it possibly have been that, had there been no donors, there would not have been a Mishkan?

So, perhaps that would have in fact, been the case. In the same vein, if one doesn’t put on Tefillin, indeed, he will have not put on Tefillin. Similarly, if people don’t eat, they would die. At the end of the day, it is up to free choice. So, yes, if there were no donors, it stands to reason that there would not have been a Mishkan.

The problem, though, is that this case really is different, because, while yes, there is always free choice, however here, it is within the system itself that G-d did not require any given individual to contribute a given amount—each of us individually was allowed to sit back and relax. So, it’s quite fortunate that it didn’t ultimately happen the way, but why did the system allow such a possibility? If the Mishkan was absolutely necessary and mandatory for the community at large, then shouldn’t there have been an absolute requirement for every single individual to provide a certain amount for the raw materials to absolutely assure that the Mishkan would be built?

It could be that the answer to this question is that as the Mishkan project was designed to serve as a communal project, it had to be kept that way in actuality. It had to remain a communal project. Had there been a direct command to each individual to provide X amount of gold, silver, copper, and so on, then by definition, it would not have been a communal project, but a bunch of isolated, personal obligations. And if that would be the case, then each person is really acting for himself and not for the greater, communal cause. Since the point of the Mishkan was for the community to get together to create a forum in which they, as a nation could house and serve Hashem, it would not have worked otherwise. It is the gathering of the community that creates the Mishkan altogether. It is the community serving together that creates Hasharas HaShechinah, the residence of the Divine Presence among the people.

That would also explain why G-d uniquely specified that for Mishkan, it would require “Kal Ish Asheir Yidvenu Libo”-“every man whose heart inspires [motivates] him.” He never said that “every man whose heart inspires him shall put on Tefillin” because it doesn’t take a special “motivation” or “inspiration of the heart” for an individual to fulfill his own personal obligations. Of course, he has to be somewhat motivated to do what he has to do, but that feeling of personal obligation creates natural motivation, when indeed, that obligation is personal. It’s when the obligation is a communal one that it gets tricky because it’s more abstract kind of an obligation. It’s not individually pressing, so the motivation is not natural.

Thus, for this communal obligation, says the Torah, it takes “Kal Ish Asheir Yidvenu Libo”-“every man whose heart inspires [motivates] him.” Because when it comes to the needs of the community, it may be that at the end of the day, I need to want it for it to happen. Because, in theory, I can contribute absolutely nothing and yet, I will not get into trouble. The project might still be finished without my help, and maybe it won’t be. But, as an individual, I must observe Shabbos and put on Tefillin—because no one can do those for me. Those are personal obligations. When it comes to the Mishkan project, yes, I might be able to sit back and let everyone else do the work. But, if every individual would think in that way, at the end of the day, the job would not get done! In order for that not to happen, for such a project, it requires “Kal Ish Asheir Yidvenu Libo”-“every man whose heart inspires [motivates] him”! It requires individuals who are motivated out of their own free will to care about—not their own needs—but those of the community, who are willing to go above and beyond, regardless of what the next person is doing, to assure that those needs are actually met the needs.

This truer sense of community, which is a prerequisite for creating a Mishkan, therefore, could not come from a mandatory tax collection, or from a decree commanding to each individual to contribute. That’s not true community, but communism. On the contrary, the Mishkan necessarily has to come from a bunch of naturally separate individuals, who motivate themselves to develop a mature sense of communal obligation and therefore contribute what they can to the cause. Those individuals will not only contribute the minimum, but they will ultimately be motivated offer whatever they could and more.

At the end of the day, that is what it takes to create a home for Hashem in the community—a sense of community in and of itself. The individuals in the community who are building the Mishkan have to want it to happen. The individuals who are building the Mishkan have to want to build a Mishkan. They have to want to serve and contribute to the needs of the community. Only when there are motivated individuals could a communal project succeed. Only when motivated individuals choose to be a community do they actually become a true community. And when such a community is formed, then the Mishkan project complete. And when such a community is formed, Hashem will reside among us.

May we all be Zocheh to motivate ourselves to not only fulfill our own obligations, but to contribute to the needs of the community, to actually develop a true sense of community with one another, and then, as result, we should be able to complete our communal project of creating a home for Hashem in the third Beis HaMikdash where He will once again reside among our national community in the days of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Josh, Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂