| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

פִּינְחָס ● Pinchas

- Why is Hashem’s recognition of Pinchas’s heroism separated from the act of heroism?

- How could Yehoshua possibly replace Moshe?

- Why is the calendar of Korbanos taught in Parshas Pinchas?

“A Moment in Time vs. The Day to Day”

Previously, in Parshas Balak, the Torah left off with Bil’am’s “Plan B” to destroy the B’nei Yisrael as he sent the Moavite and Midianite women to seduce the B’nei Yisrael and subsequently draw them towards the idolatry known as Ba’al Pe’or.1 Ultimately, the B’nei Yisrael fell for the trap which elicited a plague from Hashem against them. The people were dying left and right, all until the moment when one man, Pinchas, got up and killed Zimri, the Israelite tribal leader of Shim’on and one of the public perpetrators of the immorality with a Midianite woman.

Since Pinchas courageously exacted justice in his execution of Zimri and thereby brought the end to Hashem’s massive plague against the nation, Pinchas would be publicly recognized and rewarded with a new holy status as a Kohein and be granted G-d’s “covenant of peace.” Parshas Pinchas, our Sidrah, picks up with this historical promotion.2

EXHIBIT A: Pinchas – The Action and Reaction

Considering the above, one should already be bothered by the following question: Why did the Chumash and our Mesorah separate the passages of Pinchas’s righteous deed and its consequences into two different Sidros? Clearly, the passages revolving around Pinchas make up one larger topic, namely, Pinchas’s heroism. Wouldn’t it have made more sense to keep the two parts of the story together? Pinchas’s action and G-d’s reaction could have been consolidated into a single passage, or at the very least, our tradition could have kept them together in a single Sidrah. For organizational purposes, the tradition could have either latched the beginning of Parshas Pinchas onto the end of Parshas Balak (and the new Sidrah might have begun with either G-d’s command that nation exact retribution against Midian or with the new census). Alternatively, the Torah could have kept the title and still begun Parshas Pinchas a few verses earlier, incorporating the scene of Bil’am’s Plan B at end of Parshas Balak into our Sidrah.

Why then did the Torah and our Mesorah opt not to do that? Why was Pinchas’s execution of Zimri left in Parshas Balak while his recognition for that heroism was left to only be addressed in a separate? Is there perhaps a message being communicated by this separation between Pinchas’s deed and his reward? Why keep them apart?

EXHIBIT B: The Final Census – Those Who Did NOT Count

Following Hashem’s plague against the people and His impromptu “award ceremony” for Pinchas, Hashem directed Moshe to begin a final census of the nation, to count those who would ultimately represent the nation and enter the Promised Land.3 However, there is an elephant—actually, a number of elephants in the room within this census. The great oddity in the makeup of this census is that among all of the counted names and families, the Torah seems seems to go out of its way to mention those who had infamously died prior to this census in some noteworthy fashion.

For example, the late Dasan and Aviram are highlighted in the census. The Torah inserts their names into the lineage of the tribe of Reuvein and then rehashes for us the scene in which they joined Korach’s rebellion against Moshe and were swallowed by the earth with Korach. Here, the Torah also records the names of Eir and Onan among the children of Yehudah and then reminds us that they also died generations ago due to their own sins in the land of Cana’an. Furthermore, the Torah lists Aharon HaKohein’s sons, Nadav and Avihu whereupon it reminds us that they too died prior to this count, as they were consumed in a fire after they offered up an unauthorized incense offering to G-d in the Holy of Holies.

Obviously, these late individuals were people who would not be entering the Promised Land, and as such, they were no longer relevant to the final count, not for the purposes of war, nor for the purposes of inheriting land.Why then does the passage of the census insert their names and unnecessarily review their demise? Why use the space to make explicit mention of those who were actually excluded from the census itself? Indeed, the purpose of the census was to count who was there, not who wasn’t. Thus, those who had sinned and died literally would not count.

EXHIBIT C: Yehoshua’s Rabbinic Ordination

Aside from Pinchas himself, this Sidrah honors another man who was also promoted to a new status, namely, Yehoshua Bin Nun, who would succeed Moshe Rabbeinu in leading the B’nei Yisrael.4 The Torah relates that Moshe requested that Hashem name the next leader who would tend to the needs of the nation and guide them. Hashem subsequently commanded Moshe to lean his hand upon his student Yehoshua and ordain him as the next leader.

Now, although we have seen Yehoshua make sporadic appearances throughout the Torah, it seems as though the Torah did not have all too much to say about Yehoshua in general. In the larger Torah narrative, he seems to play the role of recurring “side character” in the few occasions he appears throughout. Even when he played a more central role in the story, for example, when he contended alongside Caleiv against the Miraglim, he still came off as more of a “sidekick,” as it was Caleiv who mainly spoke up on both of their behalves. Accordingly, we know little about Yehoshua’s character and personal attributes, let alone his credibility for the leading role, and even more than that, the role as a replacement for Moshe.

One must therefore wonder: Who really was Yehoshua? On what grounds was it that he, over anyone else, should have been chosen to lead the people, especially considering how little the Torah reveals about him? Furthermore, how could Yehoshua, or anyone for that matter, be a suitable replacement for someone of Moshe’s spiritual caliber?

EXHIBIT D: The “Korbanos Calendar”

Parshas Pinchas is also remembered widely for its enumeration of all of the Korbanos or offerings of Hashem’s appointed times.5 The Torah describes the regular daily offerings as well as the additional offerings of every Shabbos, Rosh Chodesh, and every festival. The question is why this topic was discussed here at all. The rest of the Korbanos were taught back in Sefer Vayikra. Secondly, the placement of the Korbanos calendar in Parshas Pinchas seems plainly awkward. What is its relevance here? The Torah conspicuously veered away from the historic “coronations” of Pinchas and Yehoshua to this list of recipes for the periodic animal sacrifices. What kind of culmination is this for such a Sidrah?

GLOBAL VIEW: The Theme of Legacy

Perhaps, all of our above issues can be understood more clearly if we can pin down the seeming unifying theme of Parshas Pinchas. Considering the listed topics, what exactly might we suggest is that theme? Overwhelmingly, this Sidrah, on the one hand, is largely retrospective and reflective in nature as it peers into the past of many individuals, reviewing their actions, some heroic and others less so. And yet, the Sidrah is simulatenously future-focused as it highlights the role which various individuals would play or would ultimately not play in the coming generation, based on the deeds of these individuals’ respective pasts.

These two focal points together highlight the theme of legacies. Indeed, Pinchas teaches us about the forging and perhaps the decline of individual legacies. Pinchas carried out a deed and forged a brand-new legacy for himself as he joined the holy line of the Kohanim. The Torah’s new census records the final leading lineup of troops who would enter the land, carrying forth legacies of their families. Moreover, Parshas Pinchas also famously features the righteous mission of the daughters of Tzelafchad who lobbied to Moshe for a possession in the Promised Land as a way of preserving the legacy of their father. And of course, as was mentioned, it is at this point that Hashem commanded Moshe to pass the torch to his greatest student Yehoshua Bin Nun to carry on this legacy.

But again, while this Sidrah is one whose focus is legacies, Parshas Pinchas is more specifically about the particular actions that play a role in the forging of those legacies, and perhaps the kind of conduct that would ultimately destroy them. If such a dichotomy is present, Parshas Pinchas would take us to the heart of that dichotomy and reveal the answer to a larger question, namely, what exactly the difference is between lasting legacies and those that are lost? What is it that generates an eternal legacy? What is that tragically erases a legacy forever?

DANGER: The Pursuit of Legacy

At first glance, one might say that the difference between a lasting legacy and a lost legacy is the difference between making a great and lasting impact and neglecting to do so. Indeed, there is obviously truth to this notion. One cannot expect to create a legacy by being passive and lazy. In that vein, one might intuitively conclude that to meet the goal of forging a great legacy, one must actively and ambitiously pursue that goal like any other. However, when one’s actions are decided on the sole basis of one’s future legacy, one has to be weary, because not only does the one-tracked pursuit of legacy not guarantee success, but often enough, that pursuit can become the cause of a legacy lost. That in fact seems to have been the case with many of the “ghosts” who made appearances in our final census, as it is presented in Parshas Pinchas. Indeed, the Torah points to some very great people who made incredible impact, some of who were spiritually accomplished, but their legacies were lost ironically but tragically in their very pursuit of legacy.

Though Eir, the firstborn of Yehudah clearly devalued the concept of legacy as he wasted his seed when living with his wife, his brother Onan demonstrated a brazen pursuit of his own legacy in the wake of his brother’s passing as, during what was supposed to be a levirate union with Eir’s wife—arranged to perpetuate Eir’s name—Onan selfishly wasted his seed as the progeny would not be called his.6 And as a result, Onan’s life was taken to so that he would join Eir on the bench, leaving two empty placeholders in the final census. But, what is evident is that Onan’s pursuit of legacy cost him his legacy.

Furthermore, Chazal reveal that aside from engaging in an unauthorized Temple service, Nadav and Avihu, on their exalted respective levels, each anticipated the end of Moshe and Aharon’s legacies and the beginning of theirs as they wondered, “when are these two going to die?”7 Whether these thoughts were conscious or subconscious, it was their apparent prioritizing of their own legacies that cost them their lives.

The selfish, grandeur-seeking underpinings of Korach’s rebellion are evident from the narrative itself.8 He, Dasan, and Aviram made an incredible impact, but they and their entire assembly were absorbed in their own names and ultimately lost them. There is barely a trace left of them.

We were wondering why the census would enumerate the names of individuals who literally didn’t count for the purposes of census, but perhaps the Torah was trying to highlight this very point, that indeed, they were great individuals, potential bearers of a legacy. They were individuals who should have been counted, but because of their selfish, albeit ambitious, pursuits of legacy, they would ultimately emerge with no legacy.

NOTICE: A Moment in Time vs. the Day to Day

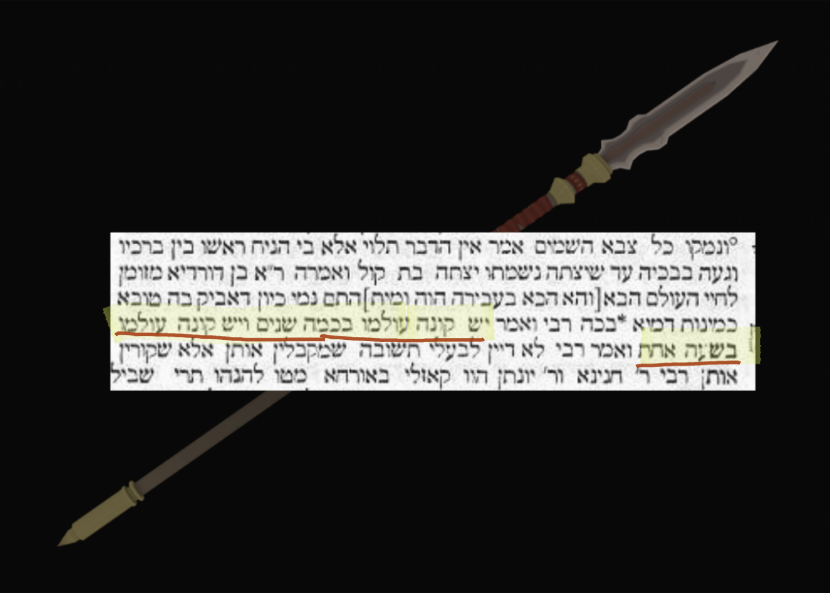

The question then is how to successfully forge a legacy. What is the appropriate route toward successfully creating a great legacy? What does it take? How long does it take? In order to answer that question, we have to refer back to those who accomplished that feat. In so doing, we will notice quickly that the answer might vary very much depending on the individual and the circumstance. To put in Chazal’s words, “Yeish SheKoneh Olamo B’Kamah Shanim V’Yeish Koneh Olamo B’Sha’ah Achas”-“There is one who acquires his eternality over many years’ time, and [yet], there is one who acquires his eternality in a single moment’s time.”9

Indeed, perhaps the two perfect models for these acquired legacies appear in our Sidrah in Pinchas and Yehoshua.

- Pinchas’s Historical Moment

Pinchas is our man of the hour, almost literally, as he undoubtedly created an eternal legacy, but in just a single moment’s time. The seeming irony in the emergence of Pinchas’s new legacy was that pursuits of legacy and “making a name for himself” were probably the last things on his mind when he performed the extraordinary deed that ultimately made those achievements happen. The Torah reveals simply that Pinchas was merely shared in Hashem’s disgrace and “zealotry.” He acted simply because he knew it was Ratzon Hashem, G-d’s Will—because someone had to do something to make things right for G-d’s sake.

We were wondering why Pinchas’s execution of Zimri and his promotion to Kehunah were separated into different Sidros, but perhaps it was to demonstrate this very point that Pinchas’s heroic ambition had nothing to do with the reward that followed. On the contrary, he undoubtedly did not anticipate the reward he was going to receive for engaging in the controversial deed he did. He didn’t know that G-d was going to publicly recognize the righteousness of his deed. But, that is the whole point. We don’t always know at the moment of our actions what the next moment is going to look like, if the public perception will be positive. We might be challenging the status quo with our action. We might make waves and receive backlash. We might have our reputations permanently tarnished. We might end bereft of legacy. But, none of these arguments impacted Pinchas’s sole desire to fulfill the Will of G-d when he needed most to do so. And because of his self-sacrifice, he ended up with an eternal legacy.

We might add that the daughters of Tzelafchad similarly acted out of their selfless goal of attaining an eternal portion for their father in Hashem’s Holy Land. They didn’t care for their own legacies, but indeed, Chazal teach us that a portion was added to our Sidrah in their merit.10 They unwittingly forged their own legacy.

- Yehoshua’s Day-to-Day Services

The other model can be found in Hashem’s selection of Yehoshua as Moshe Rabbeinu’s successor. The Midrash informs us that Moshe personally wanted his own sons to succeed him.11 However, Hashem had other plans. The question is, if not Moshe’s own progeny, who could possibly succeed Moshe and take the place of the irreplaceable?

While that is challenging call to make, Hashem had it figured out. The question is what His litmus test was. Moshe himself was intrinsically irreplaceable. How then did Hashem select a successor? The only living person who could possibly pick up precisely where Moshe left off is the one who truly appreciated most how irreplaceable Moshe was. It would have to be the individual who most revered both Moshe and Moshe’s mission. Only that man could have had Moshe lean his hands on him, symbolizing that Moshe’s life and life’s mission would now be in his hands. This ultimate reverence would not come from Moshe’s own sons who would naturally know him as “Father.” The successor of the greatest teacher could not just be a son or even just another great leader, because again, there was no one who could match Moshe or even get close. The only successor would have to be this greatest teacher’s greatest student. The ultimate reverence only can come from the student who, as close as he gets to his Rebbi and master, would still feel the awe of the aura and fire surrounding his Rebbi and master, the distance between him and his master.

Apparently, this student was none other than Yehoshua. That the Torah says little about Yehoshua and only mentions him in certain contexts is one of the biggest indicators of Yehoshua’s fittingness for the role. Yehoshua, like Moshe, embodied humility. Moshe himself would have preferred to be on the sidelines and never wanted to be in charge. He was “the one” because of who he was and because he recognized the gravity of the mission.

In the same manner, Yehoshua learned from Moshe’s way, attempting to remain on the sidelines, only speaking up when spoken to, only acting when ordered. He didn’t even receive an introduction at his first Biblical appearance in Parshas Beshalach, as his first mention is, “Vayomer Moshe El Yehoshua…”-“And Moshe said to Yehoshua…”12 as if is just assumed that Yehoshua is already standing there quietly at Moshe’s side, beck and call. It is no surprise that Yehoshua’s second mention is in the phrase, “Vaya’as Yehoshua KaAsheir Amar Lo Moshe…”-“And Yehoshua did just as Moshe said to him…”13 perhaps the perfect summary of Yehoshua’s life. In the same exact vein, it was Yehoshua who, the Torah testifies, never left from Moshe’s tent.14

How exactly did Yehoshua become Moshe’s greatest disciple? Did Moshe ever pick out Yehoshua to be his minister and apprentice? The Chumash never tells us that. However, much like Pinchas, it was the personal Achrayos or responsibility that Yehoshua felt that led him to action. He took upon himself the charge of constantly assisting and ultimately drinking from the wellsprings of his teacher, to become Moshe’s greatest student. But again, that was all Yehoshua was; the greatest student. Yes, there could be no replacement for Moshe. But no one understood how true that was more than Yehoshua did. It was Yehoshua’s grasp of this reality that made him next in line, not to become the equivalent of Moshe, but Moshe’s greatest student and the only suitable successor to him.

Now that we are perhaps satisfied with Hashem’s choice successor for Yehoshua, let us consider at what point Yehoshua earned that eternal merit. When was the great, historical moment that Yehoshua stamped his legacy? What was the incredible deed that Yehoshua performed? Was it his heroism at the scene of the Miraglim? Presumably, there was neither a single moment, nor a single deed that did it. It was the years upon years of day-to-day service to and apprenticeship under Moshe Rabbeinu. It was his lifetime of yearning, clawing, his effort and exertion that generated his lasting legacy.

But, much like Pinchas, we have no indication that Yehoshua was ever pursuing “legacy” in and of itself. He attached himself to Moshe Rabbeinu—the same teacher the entire nation had access to—because he, more than anyone else, thirsted to learn Moshe’s Torah, to thereby know and ultimately fulfill the Ratzon Hashem.

None of the above is to suggest that legacy not be on one’s mind and influence one’s actions? Perhaps, there is a great case to suggest that it should. However, the primary value that ought to govern one’s actions would have to be the one that directs him in accordance Ratzon Hashem at every given moment in time.

DISCOVERY: The Rei’ach Nicho’ach

With the above in mind, perhaps we can suggest a resolution to our final question about the end of the Sidrah, the “Korbanos Calendar.” If one takes a careful look at this “calendar,” one will notice the variation in frequency of the given Korbanos. On the one hand, the Torah lists the Korbanos of all of the holidays throughout the year. Of course, each of these holidays only occurs once a year, thus their Korbanos are offered only once annually. That tells us that there are unique moments, scattered throughout the calendar year, in which one can bring a Korban. In order to fulfill the obligations of Pesach, one had to seize the day on Pesach and offer the requisite offerings of that day. Similarly, one has only one chance in a single year to offer the unique offerings of Yom Kippur.

And yet, the Torah prefaces the “Korbanos Calendar” with Korbanos that are offered, daily, weekly, and monthly. There is a special Korban that is offered every Rosh Chodesh, every Shabbos, as well as a Korban Tamid, literally, a continual or consistent offering that is to be offered every single day of the calendar year.

Thus, between the annual Korbanos of each holiday and the Korban Tamid of every single day, we find our two models for creating eternal legacies, one in a single moment’s time, and one built on the consistent efforts of the day-to-day.

And yet, what do all of these Korbanos have in common? The Chumash relates that each of them provide a “Rei’ach Nicho’ach LaHashem,” literally, “satisfying aroma to Hashem.” But, what does that mean? G-d does not smell objects in the human sense. However, Chazal tell us famously that these words mean to convey that it is our steadfast obedience to Hashem’s Ratzon that “pleases” Him.15 Indeed, it doesn’t matter what day of the year it is. It could be the highest holiday or an ordinary day of the week. It could be a single moment in one’s life or a lifetime itself. The Korbanos reinforce the lesson that there is a requisite Avodah for all moments, and every fulfillment of Hashem’s Ratzon is pleasing to Him. Even the day to day dealings have a directive that Hashem wants us to follow and we have to always be mindful of that, regardless of what it does manifestly for one’s name or legacy.

FINAL DESTINATION: The Secret to Legacy

In the end, Parshas Pinchas divulges the secret to forging legacies. It is not simple, and in fact, it is quite tricky, because, as was mentioned, legacy and succession are apparently not the operative goals in and of themselves to attaining them. There seems to be between little and no fruitful pursuits of legacy in the Torah. Apparently, ambition to have a legacy alone could not possibly suffice.

However, the heroes and heroines of our Sidrah demonstrate that selfless appreciation of one’s responsibilities and taking initiative to fulfilling those responsibilities are a guaranteed route to forging a noble legacy. It could be one vital deed in a single moment’s time, like Pinchas’s killing of Zimri, or it could be years and years of silent devotion as displayed by Yehoshua. What they undoubtedly had in common though was that they both focused primarily on those responsibilities, producing that “Rei’ach Nicho’ach LaHashem” by being ever mindful of Ratzon Hashem. In so doing, they naturally forged their great, eternal legacies.

May we all be Zocheh to live every day and moment of our lives in accordance with Ratzon Hashem, and thereby enjoy the fruits of an eternally blessed legacy and the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bamidbar 25:1-9

- 25:10-13

- Bamidbar 26

- 27:15-23

- Bamidbar 28-29

- See Rashi’s comments on Bereishis 38:7-9 citing Yevamos 34B, Targum Yonasan, and Bereishis Rabbah 85:5.

- Sanhedrin 52A

- Bamidbar 16

- Avodah Zarah 17A

- See Rashi to Bamidbar 27:5 citing Sifrei 133 and Sanhedrin 8A.

- Tanchuma, Pinchas 11

- Shemos 17:9

- 17:10

- 33:11

- Rashi to 28:8 citing Sifrei 143