-

This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein.

It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta

-Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili

-Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha

-Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis

-Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah-Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus.בס”ד

שֹׁפְטִים ● Shoftim

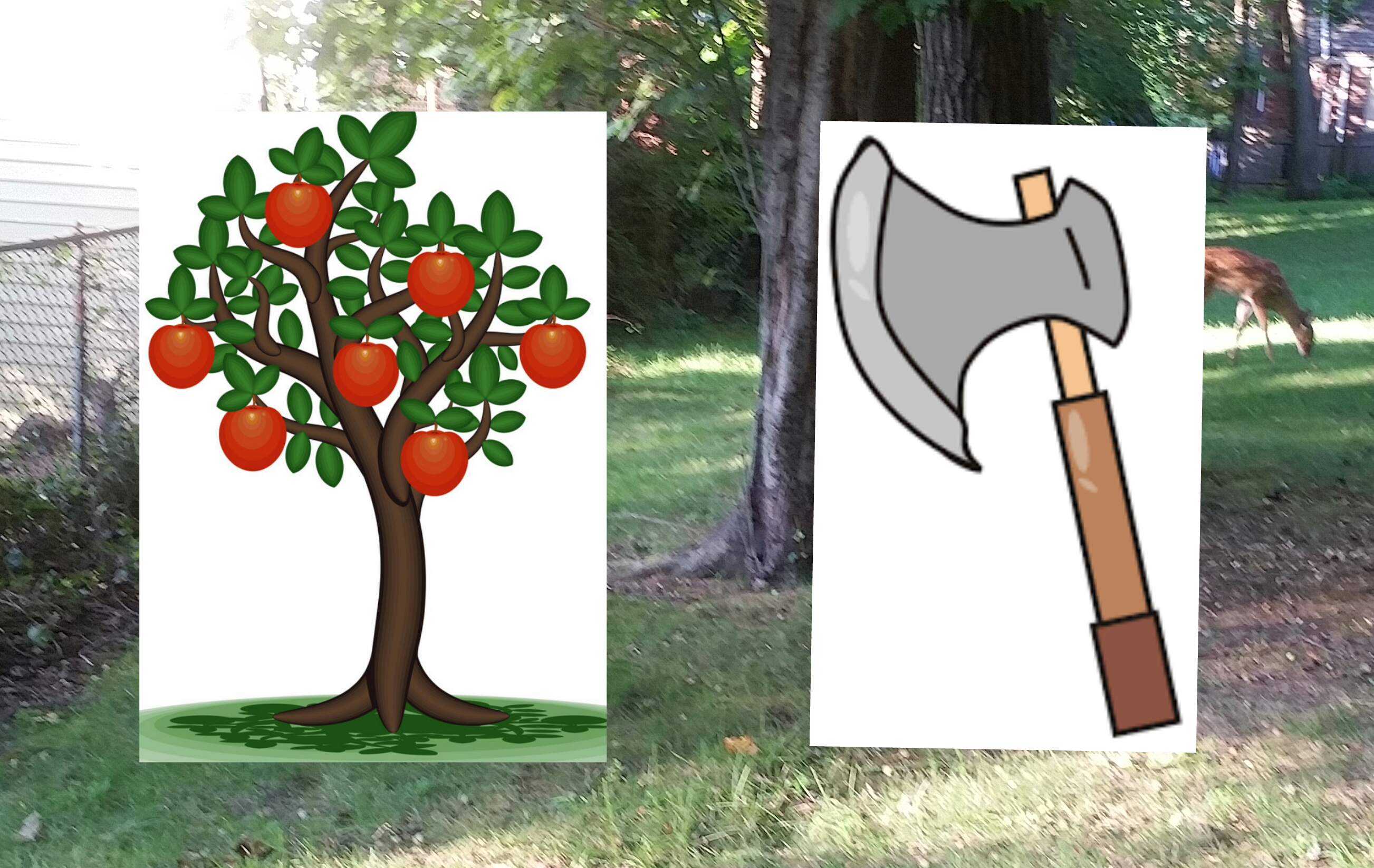

○Is there any connection between the two “tree axings” of Parshas Shoftim?

“Axe-idental or Purposeful?”

Among the Torah’s many law topics are two seemingly unrelated subjects which are portrayed strikingly on the same unique backdrop. In these two topics, we are presented with a situation which finds a person in the woods with an axe in hand and intentions of chopping down trees. Interestingly, in these apparently parallel topics, the trees are not ultimately axed. Moreover, in both scenarios, it is people who end up receiving the brunt of blade and getting killed. Finally, both of these topics appear in fairly close proximity to one another in Parshas Shoftim.

What are these two cases? The two law topics in question are that of the unintentional murderer1 and that of the destruction of fruit trees.2

TODAY’S SITES: The “Tree-Axings” of Parshas Shoftim

Indeed, as unconnected as the laws of the unintentional murderer and the law banning the destruction of fruit trees seems, their presentation in the Torah gives off the impression that they have quite much to do with one another. Among the other parallels we’ve identified, these two cases are the only two in all of Tanach which feature the Biblical word for axe, “Garzen” [גרזן], and they are, perhaps the only two cases in Scripture which explicitly reference this activity of axing trees altogether.

Again, the Torah certainly did not have to use the same unique setting to present these two law topics, and that he did so leads one to believe that it was no axe-ident. Accordingly, we must assume that he sought to communicate some deeper message between these two topics, and that perhaps the two topics shed important light on one another.

But, what is that message and what exactly is the nature of this secret relationship between the two topics of the unintentional murderer and the destruction of fruit trees? Before we can answer that question, we will have to first view these topics individually.

FIRST STOP: “A Man Falls in a Forest” – Unintentional Murder & the Cities of Refuge

When describing the laws of Arei Miklat, the Cities of Refuge—where a Rotzei’ach B’Shogeig or an unintentional murderer can seek asylum during his exile—Moshe set the stage in a forest, as we’ve mentioned, where a man was attempting to chop down a tree.1 Somehow though, the Torah writes, as the individual swung his axe, the blade flung off the wood3 and tragically landed on a civilian, taking his life on contact.

Under such circumstances, Moshe explained, that the unintentional murderer must flee to one of the Cities of Refuge to be spared from the vengeance of the Go’eil HaDam, or the late party’s “redeemer of blood.”

NEXT STOP: A Tree in the Way of War – The Destruction of Fruit Trees

In the second scenario, towards the end of the Torah’s series of laws related to war, Moshe includes a peculiar law prohibiting the chopping of fruit trees during Israel’s supposed siege of the opposing nation’s land.2 Since these trees are fruit bearing and could therefore provide sustenance and life, they were of value and would therefore remain off limits. Despite the larger goal of defeating and killing off the people of the opposing nation’s army, only non-fruit bearing trees could be axed down to advance that war effort. However, the fruit trees could not be damaged collaterally in the effort of knocking off the human enemy.

This law would become the basis for the contemporary prohibition known as “Bal Tash’chis” (lit., “do not destroy”) which commonly refers to the wasting of food.

OPPOSITE PATHS: Retzichah B’Shogeig vs. Bal Tash’chis

Now that we have laid out the two topics and scenarios of Retzichah B’Shogeig and Bal Tash’chis, we can better understand how the two topics themselves did not have to be interconnected the way they seem to have been, by way of Torah’s imagery of choice. The case of the unintentional murder did not have to take place in the forest or by way of an axe. And although the commandment against the destruction of fruit trees necessarily had to take place among the woods, it did not have to be taught in the context of war and the killing of humans.

Moreover, despite the similarities which the presentations of these two topics share, one cannot ignore the striking difference between the two cases of Retzichah B’Shogeig and Bal Tash’chis. If one thinks about it, they are practically opposites. Let us review the cases:

- Manning the Axe or Axing the Man?

In the case of Retzichah B’Shogeig, the killer was really just an innocent lumberjack. His only intention was to chop down a tree. The tree was his only target. Though he is not deemed blameless for the act of manslaughter, suppose he had been using a faulty axe or was just not careful, the fact that there was a human casualty was an unfortunate mishap. Perhaps he should have been manning the axe more efficiently, but the tragedy could have also circumstantially been avoided if the other individual had not been tragically in the way of a falling blade.

At the end of the scene, while the killer’s target, the tree, was spared, it was a man that fell in the forest that day.

- “Is the Tree a Man?”

In the second case of Bal Tash’chis, the situation is the reverse as a human killers are not innocent lumberjacks, but they are actually warriors, soldiers at a siege. The deaths that would ultimately occur among their fellow humans of the opposing army and nation would be completely intentional as it is a time of war. Humans were their true target. However, this time, it was the fruit trees which, the Torah presupposes, might get in the way of the blade, that in the process of advancing during the siege, the fruit trees might be threatened.

That the primary target is the human threat of the opposing enemy is evidenced by Moshe’s own words as he questioned rhetorically, “…Ki HaAdam Eitz HaSadeh Lavo MiPanecha BaMatzor?”-“…for is the tree of the field a human that it should enter the siege before you?”2 In other words, Moshe reasoned that it is not the tree that is their enemy or threat, but it is their human opponents. Therefore, the trees which are of substantial value should not be damaged.

Now, to summarize our observation once more, in the first context, the person targets the tree but ends up killing a man, while in the second context, the people’s primary target is man, however, amidst their particular efforts, trees are left at potential risk.

The question is what exactly we are supposed to make of these inverse cases of Retzichah B’Shogeig and Bal Tash’chis? What is the message that is being between these two cases and the mirroring imagery of axing trees and human casualties?

PATHS CONVERGE: Purposeless & Wasteful Destruction

If one thinks about that the larger goals of the individuals which we’ve identified in these two scenarios, both are outward acts of destruction. In the former circumstance of Retzichah B’Shogeig, the goal was to knock down a tree. In the latter circumstance where we encountered the prohibition of Bal Tash’chis, the case is one of war where the basic goal is to end the lives of the human opponents. Both situations entail the severing of a living organism from its life source.

Fascinatingly, the Torah was apparently not opposed to either of these goals. Chopping down trees, perhaps for firewood, is a completely acceptable behavior, assuming one is not damaging fruit trees in the process. Moreover, even going to war which requires one to take other human lives is sometimes appropriate or necessary.

However, by using the background of chopping trees for its portrayal of Retzichah B’Shogeig, or by using war as the setting for its teaching of the prohibition of Bal Tash’chis, the Torah gives enlightening context to these laws which, between these two cases, teaches us what the Torah’s attitude is towards different acts of “Hash’chasah” or “destruction.” With that said, what is the underlying issue with “destruction” of which Hashem disapproves?

As we acknowledged, the Torah can support the chopping of trees for wood and even the ending of human life for the purposes of war. If that is one’s goal, and there is an acceptable and reasonable rationale for the externally “destructive” activity he is engaged in, it is a “purposeful destruction” which is apparently not unjust. Apparently, this “purposeful destruction” which actually cuts off life is yet considered appropriate so that the Torah would not even deem it an act of Retzichah, murder, or Hash’chasah, wasteful destruction.

But in our two tree-axing scenarios, there is the potential for collateral damage with which Hashem takes issue. And whether that damage takes the form of a human life, G-d forbid, or if that damage takes the form of even an inanimate fruit tree, since the damage or casualty occurred due to recklessness or a haphazard attitude towards life—human or not—the Torah calls that an act of Retzichah of a human soul, or Hash’chasah of life-sustaining fruit tree. This damage is unnecessary and quite precisely fruitless. This damage is what the Torah will not tolerate, acts of purposeless Hash’chasah.

FINAL DESTINATION: Acts of Thoughtfulness and Purposefulness

In the end, what emerges between the Shoftim’s tree-axing cases of Retzichah B’Shogeig and Bal Tash’chis is that life of all forms is sacred that it cannot be wasted nor disregarded. The unnecessary ending of life, human or otherwise, is unacceptabe. Innocently chopping trees is not an excuse to lose control of an axe and cause fatalities. And war is no excuse to destroy everything in your path, be it a human or a tree, if that is not absolutely necessary.

In the same vein, these two law topics admonish us to act with deliberation, thoughtfulness and purpose. If one is going to sever a tree from its trunk or take a life in war, then he should do so with purpose and toward a specific goal. Because, if such acts can be deemed purposeless, then these actions could be classified as Hash’chasah or even Retzichah. In summation: Act with purpose and don’t waste life.

May we all be Zocheh to fulfill the Torah ideal of serving Hashem and acting in all facets of our lives with a sense of purpose and care for the sanctity of life, and Hashem return that same care for us and enable us to fulfill our ultimate purpose, bringing the Geulah and the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Devarim 19:4-5

- 20:19-20

- There are two opinions in tradition as to what this blade was and where it emerged from, the first being that it was blade of the axehead which was hoisted off the axe; the second opinion is that it was actually “spark” of wood which was dislodged from the tree by the force of the axe; See Rashi to 19:5 citing Sifrei 183 and Makkos 7B.