|

This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben Yosef A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. |

בס”ד

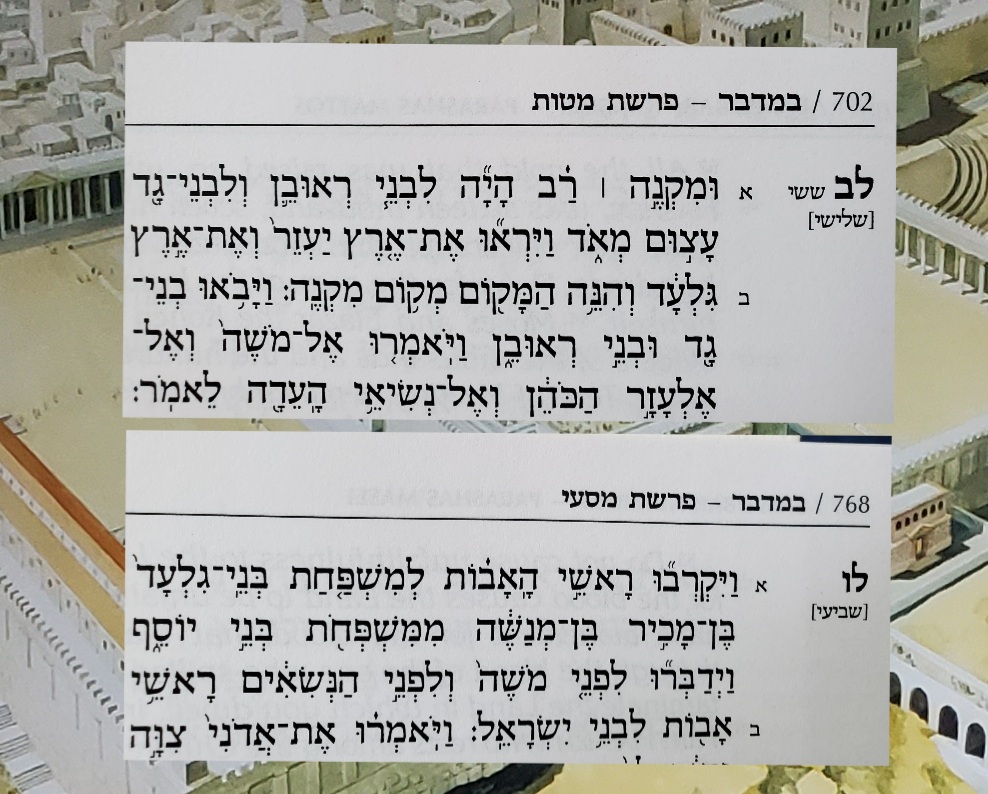

מַּטּוֹת–מַסְעֵי ● Mattos-Mas’ei

“Investing in Forever”

When looking at the double-Parsha of Mattos-Ma’sei, there is an obvious parallel shared between the two Sidros. Both conclude with a narrative in which specific tribes of Israel politely and respectfully make requests of Moshe Rabbeinu pertaining to the inheritance of land.

In the end of Mattos, it is the tribes of Reuvein and Gad looking to accommodate their livestock in the spacious and fertile lands of Sichon and Og. In the end of Mas’ei, it is the tribe of Menasheh looking to assure that the tribe does not lose land when their daughters from Tzelafchad who would inherit land would get married. Is there a lesson to be learned from these apparently connected stories?

Perhaps there are many. We’ll draw out two lessons, one lesson from a shared feature of the two stories and one from a contrast in between them.

One crucial lesson that emerges from both stories is a lesson in cordial negotiation and problem solving. Coming of the coattails of a long and complicated Sefer Bamidbar, these concluding stories have to be refreshing and quite frankly inspiring. Confrontation and complaining are a recurring theme of Bamidbar. The stories of the Mis’avim (meat “cravers”), the Mis’onenim (complainers), the Miraglim (slanderous spies), the Ma’apilim (stubborn ones), and, of course, Korach’s rebellion, all make this clear.

The players in many or all of these accounts might have had valid arguments and noticed real life problems that needed to be tended to. And in life, problems always arise and will invariably continue to do so in our imperfect world. But, how we respond to them, Bamidbar demonstrates, is the difference between the problems that will be solved and those which will be bitterly exacerbated, between those who will get through those problems and those who will be consumed by them.

The tribes of Reuvein, Gad, and Menasheh all demonstrated a beautiful lesson learned by quietly approaching their leaders with their concerns, presenting their problems, and patiently waiting for answers. None of them were turned down. They all actually were granted what they wanted. None of them lost their eternal lives because of a “problem” that got the better of them. That is one lesson from the two stories.

The second lesson emerges from a key contrast between the two stories, and it is a lesson not merely in how to refrain from losing one’s eternal life, but in how to invest in eternal life.

As was established, the tribes of Reuvein-Gad and the tribe of Menasheh both put on an absolutely incredible performance. Nothing can be taken away from the way they conducted themselves. All else being equal, we have to appreciate the vital difference between the respective requests of these two parties. Both were validated. If not, Moshe would not have conceded to any of their requests. But, were the two requests equally ideal?

We have to assume not. Reuvein and Gad’s preoccupation with the lands of Sichon and Og was due to their reasonable concern for their financial lives. Their lives and the lives of their children depended on their financial lives. Many Halachic authorities justify dwelling outside of Eretz Yisrael for financial reasons. Moshe would not turn Reuvein and Gad down. But, Chazal imply that their priorities were somewhat off. Indeed, as much as we rely on our material lives, our material lives are fundamentally transient. By now, we all have to be aware of that. All holdings in Chutz LaAretz will not last forever.

On the other hand, Menasheh was preoccupied with the Promised Land of Eretz Yisrael. That is the unmistakable, final destiny of every member of Klal Yisrael. All else being equal, we cannot forget that destiny. We cannot drop the anchor in the Diaspora and lose focus of our eternality. If for the very short time being, we need to pull a Reuvein-Gad and make due outside, there is clearly a respectful and respectable way to do so. But, like Menasheh, not only do our hearts have to always be in the direction of Eretz Yisrael, but we have to constantly recognize the transience of life in Galus and scope out steps for investing in our eternal lives. Like we would to achieve any goal, we have to plan accordingly. Only if we’re prepared to let go of the burdens of the temporary world can we invest in forever.

May we all be Zocheh to not always pursue our goals with respect, but to develop the goals, goals of eternality, and we should achieve those goals with our return to the Promised Land of our final destiny, Eretz Yisrael, as well as the arrival of the Geulah in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos! Chazak Chazak V’Nis’chazeik!

–Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂