| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah-Zalman Michoel Ben Golda Mirel-Ariela Golda Bas Amira Tova -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

**Note: This D’var Torah is a re-written, much edited, and expanded version of an old one I wrote a few years ago.

תְּרוּמָה ● Terumah

●Why did Hashem command us to donate gold? Why is it called “Parshas Terumah” and not “Parshas Mikdash”? ●

“Why Not Parshas Mikdash? – Heart of Gold”

Parshas Terumah marks the beginning of the commandments related to the construction of the Mishkan or the “Tabernacle”—G-d’s “dwelling” on earth. But before getting to the actual Mishkan-part, the reader is told simply of the raw materials that were needed to be taken to be G-d’s “Terumah.”1 With that summary of the opening verses of the Sidrah, we already have enough information to begin asking some obvious questions. Firstly, what is a “Terumah” and why does G-d want one? What purpose would this Terumah serve?

“Parshas Mikdash”

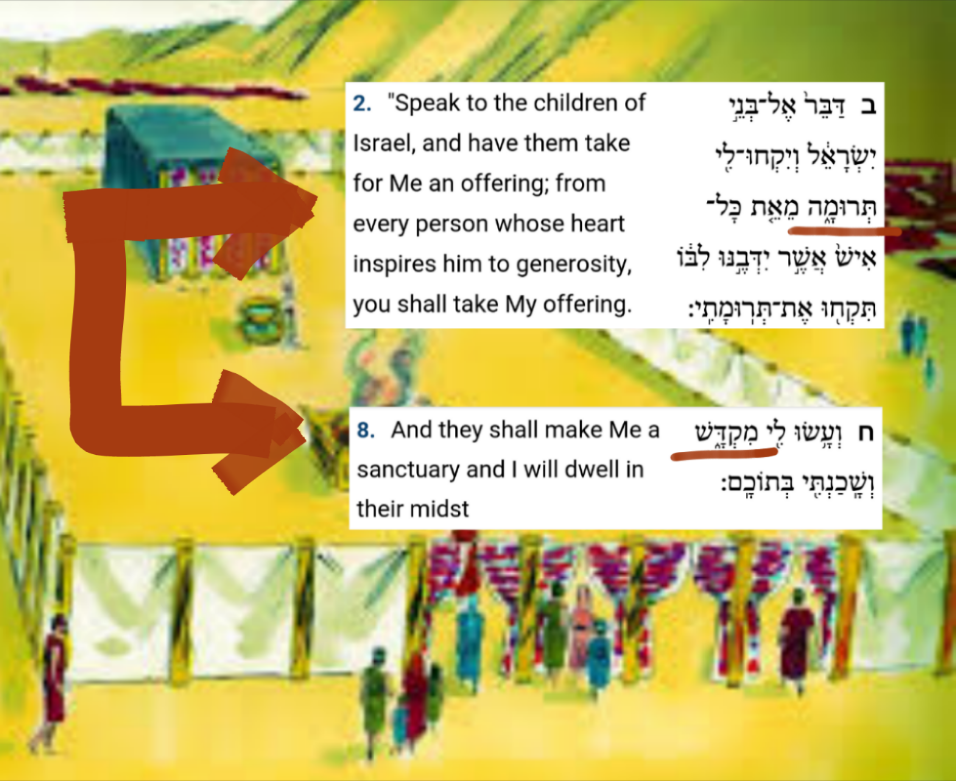

Now, of course, we know, in hindsight, that whatever a Terumah is, it was for the purposes of building the Mishkan. That G-d wants us to offer these supplies for the building of the Mishkan is stated explicitly as the Torah later commands, “V’Asu Li Mikdash V’Shochanti B’Socham”-“And they shall make for Me a sanctuary and I shall dwell among them.”2 But, if the purpose of this Terumah is the Mishkan, why doesn’t the Torah just get to the point and state that outright from the beginning without these introductory lines about this vague “Terumah” concept? The Parsha of Mishkan should begin with this mission statement!

“Vayidbaeir Hashem El Moshe Leimor: Dabeir El B’nei Yisrael V’Asu Li Mikdash V’Shachanti Besocham”-“And Hashem spoke to Moshe saying: Speak to the B’nei Yisrael, and they shall make for Me a Temple and I shall dwell among them.” Is that so difficult? According to this model, we would teach our children and all future generations this section of the Torah as “Parshas Mishkan” or “Parshas Mikdash,” either of which would serve as a greater summary and title for this Sidrah. Why not? Why is “Parshas Terumah” more appropriate? Why does G-d seem to put so much emphasis on this foreign idea known as “Terumah” and not begin His speech talking about the presumably central part, the Mishkan itself?

In this same vein, not only did the Torah not begin the Mishkan Parsha discussing the Mishkan, but the Torah chose to first mention the list of supplies before disclosing what exactly the people were to do with those supplies. The Torah goes on for seven verses before it tells us what exactly the point of this collection was. And assuming one doesn’t know better that there was a Mishkan to be built in the coming days—and as for the B’nei Yisrael then, we have no indication that they knew—then they’re bringing all of these supplies together literally for “G-d knows what.” Both, the people, at the time as well as any person learning the Parsha anew, would have no clue why all the jewelry was being amassed. So, was it supposed to be a mystery? Why not tell the people first what they collecting their materials for, from the get-go? Just say, “Okay, we’re making a Mishkan. And here are the things that you are going to need…” Why does the Torah seem to open up the Parshiyos of the Mishkan in this ambiguous, roundabout way?

Voluntary Donations Required

Another oddity in the introductory lines of our Mishkan Parsha lies in the very nature of the command for contributing to this “Terumah”; Hashem says “…V’Yikchu Li Terumah Mei’eis Kal Ish Asheir Yidvenu Libo Tikchu Es Terumasi”-“…and they shall take for Me a Terumah; from every man whose heart inspires him shall you shall take My Terumah.”1

Rashi explains that the phrase, “Asheir Yidvenu Libo”-“whose heart inspires [motivates] him” means that one was to give the offering with “Ratzon Tov,” good will, as a “Nedavah,” or a gift. In other words, man had to give it voluntarily. Now, wait one second; if this project is really a Tzivui, a command from G-d, and indeed, the building of the Mishkan is certainly counted as an individual, Biblical Mitzvas Aseih (positive commandment), then isn’t the collection inherently mandatory? If so, then how can it also be simultaneously be voluntary? That seems inherently contradictory. Plus, if it the collection was actually voluntary, then it would seem that if the people were unwilling to voluntarily give to the cause, then there would simply be no Mishkan, which is difficult to imagine. G-d’s sanctuary would become the center of our Avodah and remains what we still long for today. How could something so crucial be left to the discretion of the people? Would the entire religion have just ended there—at least the ritual aspect? How are we supposed to understand this intrinsically paradoxical command? Is this project something mandatory, resembling a Tzivui, or voluntary, resembling a Nedavah?

Hashem’s “Wish List”

In a similarly odd vein, we might point out that as voluntary an offering as this “Terumah” was, there were actual parameters for the gift. You couldn’t just give whatever in the world you wanted. You see, G-d opened up His own registry on “Bed Bath & Beyond” and wrote us up an oddly specific wish list of what was apparently required for the job at hand—gold, silver, copper, different wools, oil, etc. Indeed, if it was a purely “good willed” offering, we perhaps should have been allowed to voluntarily choose what to give. In reality, we were given a choice, but from this selection.

While we ponder this detail of the Mishkan for a few minutes, isn’t it strange that G-d even had a “wish list” to begin with? G-d told us to contribute these different materials—precious jewels and treasures. We can understand at the end of the day that these items were used for the Mishkan that we were later commanded to build. Much of the Mishkan and its Keilim or vessels are either made of pure gold or covered with gold inside and out. All of the gems and wealth were put to use in this project. But bear in mind that which we mentioned above, that initially, all we were told is that G-d wanted this “Terumah” offered to Him. In other words, before we know how these commodities would be put to use, we know that G-d sort of “required” or “requested” that we donate the commodities to Him. For whatever reason, He wants them. The question then is what particular affinity would an Almighty G-d have for physical, material riches? Before the discussion of a Mishkan comes in, why does G-d ask of us to give of these things? And even after we have established the goal of building of building a Mishkan, where did G-d’s gold standard come from? Why does He care that we specifically use these riches of all things? We can understand man wanting these things. But, the notion that G-d would value gold and silver seems petty, quite humanly, and not G-dly. At the very least, on the surface, it is theologically challenging. So, what does our material wealth mean to Him?

What is a “Terumah”?

Taking it from the top, what is the meaning of a “Terumah”? Why does our Parsha of Mishkan start with G-d’s request for this vague “Terumah,” and not for Mishkan? What is the essence of “Parshas Terumah” if not the Mishkan itself?

“Terumah,” difficult to translate literally, is referred to by Rashi as something that is “separated,” perhaps consecrated. Indeed, much later, in Parshas Shoftim3, when the Torah commands that one give the first his grain, wine and oil to the Kohein, Rashi explains that the Mitzvah is, what is referred to in Halachah, as Terumah, a designated and separated portion. R’ Shimshon Raphael Hirsch takes the word “Terumah” a step further and relates it to the root word “Rom,” or “Romemus,” meaning something lofty or elevated. Accordingly, “Terumah” is an elevated portion. The point is that when one offers Terumah, essentially, what he is doing is taking a portion of his own aside and reserving it for a higher, holier purpose. One takes a share of himself and sets it aside saying, “This part is for Hashem.” This deed is the core of Terumah.

Above all else, this message is what Hashem wants to convey. But, isn’t the point that we are supposed to build a Mishkan? Indeed, the command take a “Terumah” is not an exclusive command, intended to “outshine” the command for a Mishkan. The Mishkan is the focal point and physical manifestation of this larger project, yes, but the fundamental goal, the project itself is actually the Terumah, the elevated portion. Because what is, in fact, the function of the Mishkan? As was mentioned, the Mishkan is G-d’s “dwelling” on earth. What exactly does that mean though? How do you make a place for G-d on this earth? It needs to be constructed especially from the materials of G-d’s Terumah, the portion of this world which designated and elevated for that very purpose! Whenever and wherever we cordon off a reserved portion, of our assets, our time, or even ourselves, for Divine service as an offering to Hashem, then in those zones may G-d dwell. The Terumah is not just the prerequisite for, but the essence of what a Mishkan is! It is an elevated earthly space for Divine Presence. G-d—and His Mishkan—are wherever we personally make room for them and allow them into our lives. It is the “Terumah” that precedes and encompasses the Sidrah of Mishkan! Without Terumah, we can’t truly understand or even begin to build the Mishkan. The Mishkan is a manifestation of our Terumah—our designation of a sincere portion of ourselves to G-d, allowing Him into our lives to dwell among us. That is Parshas Terumah!

“Rachmana Liba Ba’i”—Heart is Required

The above may shed light on the seemingly enigmatic nature of the command for this Terumah, the contributions for the Mishkan. How can it be a command, seemingly mandatory, yet, simultaneously voluntary? Indeed, it is a Mitzvah. Intrinsically, like any other, it has to be an imperative. By Torah law, there had to be a Mishkan. However, perhaps an aspect of the Mitzvah had to be voluntary. Man had to contribute something to the cause with this good will. And apparently, it is not a contradiction. Although ideally, all Mitzvos should be done with good will, apparently, for the Mishkan, for this Terumah, the good willed contribution is an intrinsic component of this mandatory commandment. To build an apartment for G-d in this world simply won’t work if we don’t give with the correct mindset. It just won’t work if our hearts are not in it, if we don’t want it to work. Why would G-d require this caveat? Why do we need to give Him with good will?

Because, G-d is so overwhelmingly beyond this world, He can only be allowed into our lives if we have that good will to properly invite Him in. Whether or not we invite Him, as imperative and mandatory as it is, is up to our choice. The negative extreme is that we can ignore G-d, snubbing Him, making no room for Him, so that perhaps, He will have to insert Himself into our lives in an unpleasant fashion. But, we don’t need to go to that extreme. We can theoretically pay attention to Him and technically go through the motions of “bringing an offering” to G-d, but without the requisite goodness of heart. Indeed, even Kayin knew that He had to give something, thus, he the first one that the Torah records as ever having brought a offering to Hashem.3 But, how much we choose to give, and how we choose to give is an entirely different story. All of that remains our choice. Thus, we can practically give to the “Mishkan fund,” but still fail to create a space for G-d in this world if we lack the mindset of this need and yearning for G-d’s Presence, to be a part of Him and want to somehow give back to G-d in any which way possible.

At the end of the day, G-d owes us none of the assets He gives us constantly, and we endlessly owe Him back. The sense of obligation is there existentially, but the sense of yearning must come from within. To have G-d Present in our lives can only make sense logistically if our hearts are in it. That is what Chazal meant when they taught, “Rachmana Liba Ba’i”4—“The Merciful wants”—or better yet, “needs the heart.”4 Indeed, for Hashem to truly dwell among us as is the apparent goal of the Terumah, how can it be done without each person’s individual will that He do so? The amount we give depends is up to our heart’s desire. If we greatly desire Hashem to among us, the more and more room we will reserve for Him.

The Heart of Gold – Hashem’s Gold Standard

Now, if we’re being given this discretion as to how much we can designate for Hashem, why does G-d specifically set up this registry, requiring gold and material riches from us? Why does He care for the physical wealth at all?

Perhaps, G-d is asserting another key lesson of Terumah, perhaps that which Kayin was missing, but which his younger brother Hevel realized. Does G-d need our gold or our money? Indeed, He does not. Does He value our gold or any of our physical commodities in and of themselves? Of course not. G-d can can get all the gold in the world on His own if He wants—it’s all His. “Li HaKesef V’Li HaZahav Ne’um Hashem Tzeva’kos”-“Mine is the silver, and mind is the gold, says Hashem of Legions.”5 In fact, Hashem gave the people all of the gold they were currently enjoying. Hashem could have decorated His own Mishkan with the rings of Saturn and wings of angels if He so pleased. G-d however desired the gold and silver of man because man holds his gold and silver in high regard. It is what man has and values that G-d wants.6 Of man’s precious, prized possessions, man owes a portion back to Hashem. Right, one can theoretically give something and devote some time and Mesiras Nefesh, giving over of oneself to Hashem. He can choose the amount. But there’s a caveat. One can’t play G-d and leave Him the short end of the stick. Hashem has a “gold standard.” He demands quality—that which we admit is quality. He wants our treasured “gold.”

Indeed, while on the surface, it seems that we need our hearts to motivate us as a means to contribute gold, in reality, it is actually the gold that is the means to the end which sees us giving our hearts to the project. Indeed, it is not fundamentally the gold of the heart itself, but it is the heart of gold that the Mishkan requires of us, that G-d wants of us. Hence, “Rachmana Liba Ba’i”-“The Merciful wants the heart.”4

The very same goes for our Mitzvos and Avodas Hashem at large, which G-d too does not intrinsically need. Hashem knows we’re limited and can’t literally give over all that we have Him, but we owe Hashem a sincere portion. We owe Him quality. That is precisely what the Rabbanan of Yavneh intended when they famously stated, “Echad HaMarbeh V’Echad HaMam’it U’Bilvad SheYichavein Libo L’Shamayim”-“One may do much or one may do little; provided that he [truly] directs his heart to heaven.”7 Indeed, when we not only set aside a “generous” portion to Hashem, but our hearts motivate us to give our very best, despite the given quantity, Hashem detects it, senses the quality and passion of our hearts, and He is sure to dwell in our midst.

May we all be Zocheh to set aside and devote our very best quality of Mesiras Nefesh and heart to Hashem’s Avodah and He shall eternally dwell among us with the coming of the Geulah in the times of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos and a Simchah-filled Chodesh Adar!!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Shemos 25:1

- Ibid. 25:8

- Bereishis 4

- Brachos 5A

- Chaggai 2:18

- I later heard this very idea suggested in the name of the Dubna Maggid as well.

- Brachos 17A