This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H & in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for:

-My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel

-My grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Sarah Leah

-My grandmother Channah Freidel Bas Sarah

-My great aunt Rivkah Bas Etta

-Chaim Reuven Ben Liba

-Aviva Malka Bas Leah

-And all of the Cholei Yisrael

-It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamah of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, and for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. We all need Moshiach now.

בס”ד

תּוֹלְדוֹת ~ Toldos

“He was Called Red; Eisav Spades”

Genesis.25.25

Yaakov said, “First sell me your birthright.”

And Eisav said, “Behold, I am going to die, so of what use is my birthright to me?”

וַיֹּ֖אמֶר יַעֲקֹ֑ב מִכְרָ֥ה כַיּ֛וֹם אֶת־בְּכֹֽרָתְךָ֖ לִֽי׃

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר עֵשָׂ֔ו הִנֵּ֛ה אָנֹכִ֥י הוֹלֵ֖ךְ לָמ֑וּת וְלָמָּה־זֶּ֥ה לִ֖י בְּכֹרָֽה׃

Yaakov said, “First sell me your birthright.”

And Eisav said, “Behold, I am going to die, so of what use is my birthright to me?”

וַיֹּ֖אמֶר יַעֲקֹ֑ב מִכְרָ֥ה כַיּ֛וֹם אֶת־בְּכֹֽרָתְךָ֖ לִֽי׃

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר עֵשָׂ֔ו הִנֵּ֛ה אָנֹכִ֥י הוֹלֵ֖ךְ לָמ֑וּת וְלָמָּה־זֶּ֥ה לִ֖י בְּכֹרָֽה׃

Genesis.25.30-32

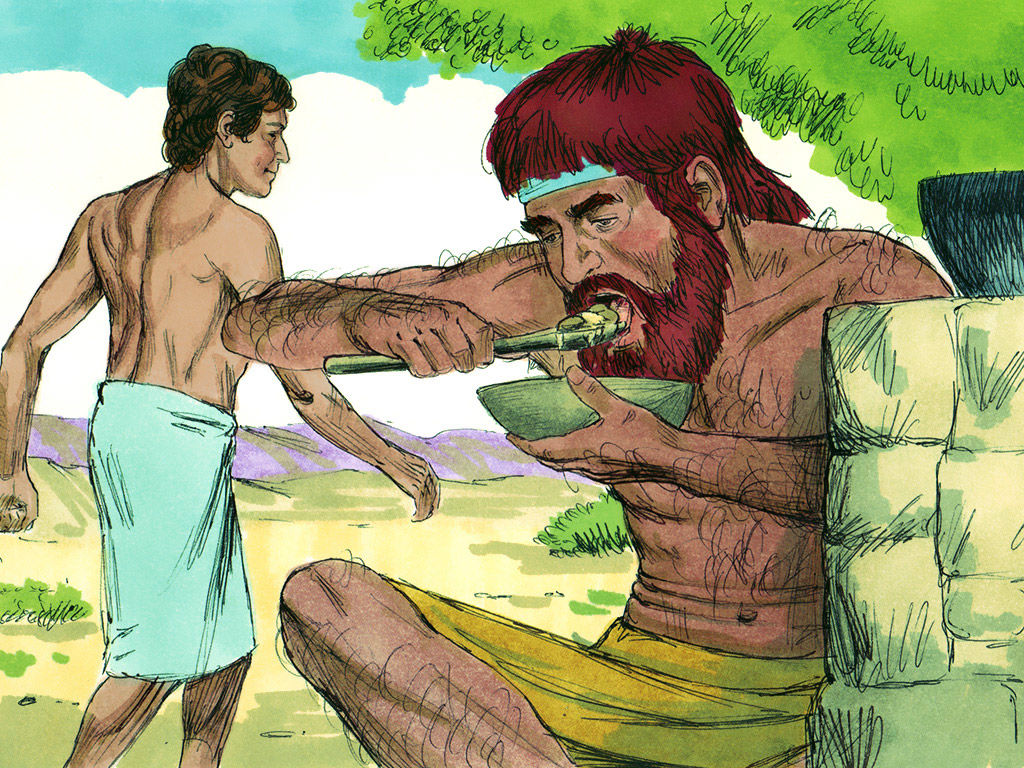

The feud between Yaakov Avinu and Eisav HaRasha, on the surface, begins with a business transaction involving Yaakov’s bowl of lentil soup and Eisav’s Bechorah, or birthright status [Bereishis 25:29-34]. As the story goes, Eisav comes home from the hunt exhausted and hungry, meanwhile, Yaakov is cooking the lentils. Eisav requests the lentils, whereupon Yaakov concedes to give him the lentils only if Eisav swears to sell him and ultimately relinquish his birthright to him. Eisav rationalizes that the birthright is useless to him, so he agrees and apparently “spurns” or snubs the birthright.

In this mini narrative, the Divine Narrator or Editor inserts a seemingly strange phrase. Eisav comes in asking the lentils saying [25:30], “…Ha’aliteini Na Min HaAdom HaAdom HaZeh Ki Ayeif Anochi…”-“…‘Pour for me now [please] from this red stuff [lit., the red, the red] for I am tired,’…” to which the Narrator interjects [Ibid.], “…Al Kein Kara Shemo Edom”-“…therefore, he was called Edom [Red].”

Now, this note is strange on multiple accounts. First of all, why is it so significant that he called the lentils “red stuff” that he was nicknamed for life because of it? Who cares what he called the lentils on that one occasion? His choice to call the lentils “red stuff” seemingly has no significant bearing on his life afterward. (Even if the selling of the birthright was a significant factor later in life, what he called the pottage of lentils in the story, shouldn’t ultimately matter.)

Moreover, why is the fact that Eisav called the lentils “red stuff” a good reason to call him “Red”? Of all options, that Eisav called the lentils “red stuff” is truly a silly reason to name him “Red.” If anything, the reason why he should be named or called “Edom” is that the Torah itself attests to the fact that indeed, Eisav was red! “Vayeitzei Rishon Admoni…”-“And the first one emerged a red [ruddy] one…” [25:25]—Eisav had a ruddy or reddish complexion, perhaps he was a redhead. Either way, he a “red” way about him, and in fact, Eisav’s personal redness is an aspect of Eisav which Chazzal derive a lot of symbolic significance from [e.g. Rashi to 25:25 citing Bereishis Rabbah 63:8]. If there is any reason why people would refer to Eisav as “Red,” this has got to be it. But, who cares about what he called the lentils?

Interestingly, the Rashbam [to 25:30] comments on the apparent pattern that Eisav “was red and he desired to eat red,” which makes it seem like Eisav was “all about” red, that perhaps there are multiple reasons to call him “Red.” But which one is Eisav really named for? Is he named for both? The Torah evidently ascribes the name to the lentil story, seemingly to the exclusion of the fact that he was a “red” person. But, again, why do we care about what he called the lentils?

The simple answer to these questions might be that, yes, in truth, what Eisav called the lentil soup, intrinsically, should not have been a significant factor in the story, however considering the story’s larger implications, what he called the soup, in hindsight, actually becomes significant.

What are the larger implications of the narrative? As was explained earlier, Eisav sold and thereby spurned the Bechorah. What does that mean that he spurned the birthright?

It doesn’t mean that Eisav merely made a bad business deal. Spending thousands of dollars on a broken refrigerator is a bad business deal. The idiocy of such a deal is tangible and palpable. But the selling of birthright is something else entirely, because it is completely intangible—not meaningless or insignificant—but certainly intangible.

The problem with this transaction is more subtle than just throwing out good money. That Eisav could reason that the birthright is useless and ultimately sell it away for a single meal is a testament to the fact that he undoubtedly thought he was making, not just a good deal, but a deal that was a no-brainer—that he was ripping Yaakov off. In his own mind, he was spending zero dollars, essentially, to “purchase” or really just snag a free lunch. The only person who could do this is someone who does not see or appreciate the deeper significance of that which he is giving away. The spurning was not a result of the fact that the deal was in actuality a rip-off to Eisav, but that Eisav took something which should have been priceless and treated it as though it were worthless. Why or how could he do that? Because, again, the rights to being firstborn are intangible, and therefore, on the surface, mean nothing. Sure, the firstborn receives certain spiritual entitlements—the heir to Yitzchak would carry forward Avraham’s spiritual mission of spreading the word of G-d to the world. And even from a materialistic perspective, the firstborn receives a double portion from his father’s inheritance in the distant future. But, right now, it was of little relevance, because apparently, Eisav was not concerned about the future, but rather about what he sees in front of him here and now. That was what Eisav appreciated.

And this very attitude which led Eisav to make the sale is imbedded in the way he described the lentils, not for what they were in their essence, but for what they were externally, just plain “red stuff.” He described them by their color, a superficial feature of them. This insignificance he ascribed to the lentils, alone, was not why he was named “Red.” The insignificance he ascribed to the lentils was reflective of a larger worldview, that nothing is particularly significant or sacred. The insignificance Eisav he ascribed to the lentils represents the insignificance Eisav ascribed to the birthright, spirituality, and most of life at large (it happens to be that in this story of the selling of the birthright is where this attitude might have costed Eisav the most). Eisav didn’t look at the essence or intrinsic meaning, the eternal consequences of everything in life, but at the surface, the externals. And it could be that with this same rhetoric, Eisav himself is nicknamed, yes, for his choice of words, but perhaps as well and even more significantly, for his color—for the external detail about himself. In other words, just like Eisav named things superficially as is appropriate in Eisav’s worldview where only the outside that matters, he too is named superficially, “Edom.” He was just a “red” guy. Nothing deeper or beneath the surface.

But is everything we’re saying about Eisav’s attitude completely true? Did Eisav not consider anything significant or sacred? While in our narrative, Eisav looks as though he doesn’t care about anything spiritual, fast-forward to the scene of the blessings, when Rivkah arranges for Yaakov to trick Yitzchak into blessing him instead of Eisav [Bereishis 27], Eisav is furious about having lost out on the blessings! He begs Yitzchak to give him some blessing and actually breaks down into tears over the blessings! He certainly acknowledged the apparent significance of the spiritual phenomenon that existed around him, did he not? Why should we insist on presuming that Eisav was this primitive, unsophisticated and purely superficial individual? While many may imagine him as just this hairy Neanderthal or caveman in a loincloth holding a massive stone club, yet, there was certainly more to him. He not only apparently appreciated the blessings, but Chazzal present him as being clever [Rashi to 25:27 citing Bereishis Rabbah 63:10], so he was apparently somewhat of a sophisticated and intellectually skilled individual, a quality of great value in the spiritual realm as well. So, what was it about Eisav? Did he appreciate spirituality and the meaning of life or not? Why do we name him according to his less than sacred view of life, if we see that in certain instances, he valued that which was sacred?

So, as for this question, we must understand that Eisav was certainly not just a fool or a “caveman.” He undoubtedly had some kind of appreciation for spirituality, at least at certain points of his life. As was mentioned, he wanted the blessings from his father. But, if he cared about spirituality and was a clever individual, why did Eisav sell his birthright earlier? It could be that as per Eisav’s worldview of looking at matters based on the surface, while Eisav might’ve subscribed to the existence of some spiritual significance in life, he only appreciated it when it would convenience him immediately. He was intelligent enough to evaluate the things in his life and even get what he wanted from the world—but only insofar as it benefited him now. That’s why, when he and Yaakov were young, the birthright was meaningless, but when he was older and Yitzchak was prepared to die, the blessings and likely the birthright were now meaningful. Yes, he believed in the power of the blessings—but he only wanted them because they could be of material use to him right now. In this exact vein, he made a lot of use of his intellectual ability—whenever he could gain something tangible from doing so.

It is in this vein that Chazzal warn us in Pirkei Avos [4:5] not to make the Torah into a Kardom, a spade or a shovel, to dig with it. What do Chazzal mean that we shouldn’t make it into make it into spade? And why do they choose this object? In other words, Chazzal are telling us that, while, of course, we have to fulfill the Torah and our spiritual potential; however, we are not to turn the Torah into a tool for our personal gain. Because then, we ultimately sully it in dirt, like a shovel, because we think it will be materially useful to us in this world. That’s a misuse and a lack of appreciation for the Torah and spirituality. It’s a spurning of that which is actually meaningful. It is selling the Torah and its pricelessly spiritual significance short. It is the only circumstance under which Eisav truly had an appreciation of spirituality. Spirituality was his spade, so that when it could be immediately useful, he exploited it, and when it would not he ignored it. But, either way, he spurned it.

All of the above is an outgrowth of this narrow worldview of Eisav’s that whether intrinsically material or even spiritual, all that mattered was in front of him now. It is the reason why he is named merely after an insignificant, surface feature, “Edom”-“Red,” whether the color of his skin or hair, or even the way he described a bowl of soup. This worldview limited Eisav to evaluating life only in terms of the here and now, and it was why even the spiritual matters which he did appreciate, he only appreciated them on the surface, but spurned them for their true essence.

May we all be Zocheh have true appreciation for the Torah and the priceless portion we have in our spiritual lives, not sell ourselves short in spirituality, but invest in our spiritual future, so that we will be able to appreciate the eternal fruits of our investments both in This World and soon in the Next World with the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos/Chodesh Kisleiv!

-Josh, Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.