| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah-Amitai Dovid Ben Rivka Shprintze -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

בְּהַעֲלֹתְךָ ● B’Ha’alosecha

● Why did the Chumash insert a “Book” of two verses in the middle of the Torah narrative? ●

“Editor’s Note: A Relocated Book”

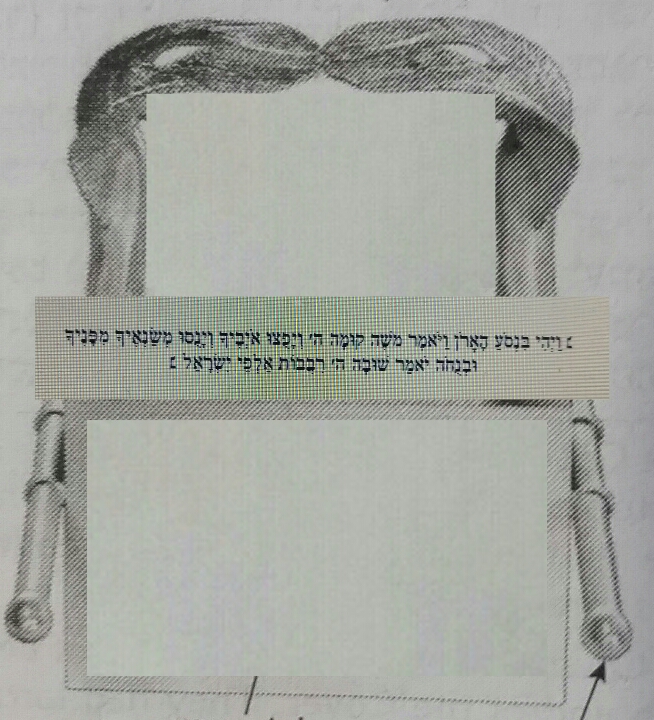

A strange feature of Parshas B’Ha’alosecha is that which Chazal refer to in the Gemara as a “Sefer” or a “Book,” containing two verses which were apparently uprooted from their original position and inserted at a seemingly random point in the narratives of our Sidrah.1 This “Book” is hard to miss as it is conspicuously bracketed off with two inverted letter Nun’s [׆], one at each end, specifically to inform us that these verses don’t actually belong where they appear.2

We will shortly attempt to decipher the precise reasoning for this Divinely ordained “edit” which Chazal have identified, but before we do, let us just get familiar with this “Book.” What are the exact contents of this “Sefer”?

TODAY’S SITE: The Relocated Book

The verses of this “Book” are none other than the famous Pesukim describing the traveling and resting of the Aron, the first of which is nowadays recited before every public Torah reading, and the second of which is recited afterward:

“Vayehi Binso’a HaAron Vayomer Moshe Kumah Hashem Viyafutzu Oyivecha Viyanusu Misan’echa MiPanecha; U’Vinuchoh Yomar Shuvah Hashem Rivevos Alfei Yisrael”-“And it was when the Ark would travel, and Moshe said: ‘Arise, Hashem, and let Your enemies be scattered, and let Your haters flee from before You.’ And when it would rest, he would say: ‘Return [home], Hashem, [to, among the] myriads of thousands of Yisrael.’”3

Rashi directs us to the aforementioned insight of Chazal that these verses are actually their own separate “Sefer,” “relocated” or “repositioned” here from their original spot. Why exactly were they inserted here? Chazal explain that they are specifically to serve as a “Hefseik” or to separate between the first “Puranus” or “tragedy” and the second one. What were these tragedies? The Gemara tells us that the first tragedy was the insulting manner in which the B’nei Yisrael rushed away from Hashem when they left Har Sinai4 and second of the tragedies is the B’nei Yisrael’s baseless complaining in the desert.5

SCAVENGER HUNT: The Standing Questions

Though there are perhaps many different questions that one might ask about Chazal’s assessment of this mysterious “Book,” there is a specific set of difficulties that have to addressed, which, if left unresolved, will hinder our ability to appreciate and even glean a simple understanding of the tradition as it is found in the Gemara.

- Why separate these “tragedies”?

Firstly, why did the “Divine Narrator” or “Editor” feel the need to interrupt or separate between the narratives or tragedies in the first place? Is it because the events are negative and reflect badly on the B’nei Yisrael? That hardly seems to be the case as such a cause does not stop the Torah later from listing tons of “Jewish” sins in succession from the second half of B’Ha’alosecha all the way through to virtually the foreseeable remainder of Sefer Bamidbar. Indeed, Sefer Bamidbar is an extended series of unfortunate events for the B’nei Yisrael, but we don’t find any effort—no strings pulled or texts edited—to ultimately separate them. Why are these tragedies different? Why is it that here, these there are misplaced verses and signals inserted to divide the accounts?

- What was the “first tragedy”?

The second of the two tragedies is clear. The Chumash tells us that the B’nei Yisrael complained. The question is what exactly the first tragedy was. From a simple glance of the Gemara, what the first tragedy was is simple; the B’nei Yisrael disrespectfully turned away from Hashem’s Presence at Har Sinai. That is what the Gemara records plainly. Ramban adds that the B’nei Yisrael were afraid, as it were, of possibly receiving “more Mitzvos,” and so, they escaped Har Sinai like children being dismissed from school. The problem is, though, that if one takes an honest looks at the text preceding the “Book,” it seems as though the B’nei Yisrael had done nothing wrong or even contraverial at all. All the Torah tells us is:

“Vayis’u MeiHar Hashem Derech Sheloshes Yomim V’Aron Bris Hashem Nosei’a Lifneihem Derech Sheloshes Yomim Lasur Lahem Menuchah”-“And they traveled from the mountain of Hashem a three day journey, and the Ark of the Covenant of Hashem was traveling before them, a three day journey, to seek out for them rest.”6

The actual Pasuk, from the outset, looks quite innocent. They traveled from Har Sinai as they were expected to. Why should we assume that there was something disgraceful or insulting about the way the B’nei Yisrael left Har Sinai? What forced Chazal to read this apparent condemnation of the B’nei Yisrael into the text, and veer from the principle of “Dan L’Kaf Zechus,”7 of judging favorably? If there was something truly despicable or tragic about the B’nei Yisrael’s first steps away from Har Sinai, why didn’t the Chumash spell it out?

Certainly, if there was a concern that successive sins would reflect badly on the B’nei Yisrael, we wouldn’t require any separation to mask that succession here. The first “sin” or “tragedy” here is hardly noticeable. Why then would we need to inject this “bracketed section” into the narrative and separate the events?

- Why insert the passage of “Vayehi Binso’a”?

The final issue we have to address is apparent choice of verses which the Divine Editor used to divide the narratives. Is there any rhyme or reason behind the insertion of the passage of “Vayehi Binso’a” specifically? Were they arbitrarily selected? Why are these verses describing the traveling and resting of the Aron during the journey through the desert the most appropriate ones to be relocated here for the purposes of “separating” the two tragedies?

HIDDEN LEDGE: An Unpredictable Turn

Our first question regarded the Torah’s apparent need to separate these particular tragedies among the many recounted in Bamidbar. We raised this question from the standpoint of hindsight. Indeed, we know in hindsight that the Torah, after this point, features plenty of “negative” stories and sins of the nation in rapid succession. However, that downward spiral should be disconcerting. Although, as we’ve explained in earlier discussions, the B’nei Yisrael had never been perfect and they have been the subjects of sin and tragedy before, until this point, there had never been such an intense series of disasters as they occurred in Sefer Bamidbar from his point on onward.

Moreover, without this hindsight, we would undoubtedly argue that the overwhelmingly negative turn for the B’nei Yisrael in Bamidbar was largely unforeseen. For anyone who didn’t know better, most of the misfortune that is recorded in Sefer Bamidbar should not have even happened. The nation was just counted in a census and set up in formation for what was supposed to be a swift, smooth and unhampered trip into the Promised Land. However, in our Sidrah, tragedy struck unexpectedly and just snowballed out of nowhere. Something, at some point, went wrong.

The question is what happened. Where did things go wrong? Why and how did it happen? If one looks at the text, as we’ve explained, it is really not at all simple to tell. From the straightforward text, it looks as though, one day, the B’nei Yisrael just decided to complain.5 Strangely enough, the Torah doesn’t even mention what it was that they were complaining about. In subsequent verses, the Torah informs us that nation had a desire for meat, an aversion to the Manna, and records other such issues and complaints. But those verses were indeed referring to subsequent complaints. However, the beginning of the negativity, back at square one, is not solicited by anything specific. It all started with mere groaning out of some unrevealed frustration.

Indeed, it is challenging to tackle the root of this issue when the Torah is beginning with such a vague plotline. If there was a real reason to complain, why wouldn’t the Torah tell us what it was? And if there was no real reason to complain, why were they complaining? Something had to be bothering them. What was the source of their problems?

BACK TO POINT A: The “First Tragedy”

Indeed, as we just discussed a short while ago, Chazal informed us that the series of unfortunate events did NOT begin with the vague complaining. As Rashi and the Gemara described, the “relocated” passage of “Vayehi Binso’a” appears in between two apparent calamities, the event of the complainers being the second of the two. The first one, as was mentioned, was B’nei Yisrael’s hasty parting from Har Sinai. And we were bothered because there is no apparent fault of the B’nei Yisrael specified in their leave from Sinai. If this is the beginning of all the misfortune of the latter half of Sefer Bamidbar, then we’re more lost than we were before, because if the cause for complaining was not apparent, neither is the tragedy that started it all. The root of the downward spiral is not at all apparent.

BEWARE: The Divine Editor’s Note

Indeed, the beginning of the end is obscure, but perhaps this exact challenge is precisely the answer to our other questions. We were wondering why the Torah needed to “separate” between the tragedies at all, and why we specifically needed to superimpose this “bracketed section” to separate calamities when the first one is barely visible. But, perhaps these two questions answer each other. We needed the bracketed section to separate and thereby demarcate that indeed, there are successive tragedies unfolding here. Because, indeed, the verse does look innocent. It does not seem that the B’nei Yisrael did anything wrong here.

Thus, enter the “Divine Editor” with the apparent “disclaimer”: “Something is the matter over here. If you want to know why the rest of this book does NOT tell the story of the B’nei Yisrael’s immediate entrance into Eretz Yisrael and why it will recount a series of unfortunate events, the critical issue lies in this hidden tragedy.”

Chazal and the Rishonim picked up on these signals, read between the lines, and identified the latent urgency of the nation to escape Hashem’s Presence, relieved, in a sense, children who are being dismissed from school. Chazal realized that they didn’t just travel but they traveled away from G-d.

But if the B’nei Yisrael truly fled from Hashem, why didn’t the Torah spell out that they did so? It could be that the reason why it wasn’t so obvious from the text that the nation ran away and why it took Rabbinic exegesis to uncover this jaded attitude of the people was that, in fact, that jadedness was ever so subtle. We could perhaps suggest that the nation did not literally celebrate their dismissal like children from school and perhaps they did not even literally voice anything cynical at that moment either. But, perhaps there was an unvoiced and still somewhat palpable feeling of apprehension that the people manifest in relation to their responsibilities. Perhaps there was a sigh of relief upon their departure from Sinai. They left the mountain of G-d and didn’t look back because they nervously foresaw the burden of responsibility. They had a slowly surfacing desire to back out.

Even if we would take Ramban’s analogy to school children on its face, not all children utterly despise school to the core—though some do—most children just prefer not to be in school and would rather be on vacation. But, who wouldn’t? It doesn’t mean that they could think of nothing that they enjoyed or even think they’ve gained from school. The B’nei Yisrael likely felt the same way; they understood the theoretical “prize” of being G-d’s people, but did they did not as much enjoy the burden of responsibility, because again, who does? Moreover, who said that they were going to succeed in fulfilling their responsibilities? Who is going to assure it? Thus, they weren’t so sure about what to make of Torah observance.

Their inspiration and morale weakened, and slowly, so did their faith in the entire mission. Their enthusiasm faded. During that time, pessimism, cynicism and other negative feelings began to build up. But no one event caused it. It was a matter of attitude, nothing more major than that though; a little loss of enthusiasm and some new, adolescent-like jadedness.

Why did they complain in the very next scene? We might never know, but we know that they just complained—it could have been about anything. In fact, it probably was nothing specific. They just had an underlying negative attitude which made them irritable in the face of any slight discomfort. Being G-d’s people just wasn’t as simple as they had once imagined it would be. They did not appreciate the task the way they used to.

Now that we’ve divided up the scenes and the Torah has outlined the starting point or the subtle breaking point, we can determine where, why, and how everything went wrong. A simple attitude problem escalated. The people preferred to opt out of their mission, and in the long run, no one was going to force them to keep to it. From that point, it was easy to come up with a pretext for complaining every single step of the way, and that the B’nei Yisrael did. Why all the subsequent negative events occur, and why the B’nei Yisrael still have not yet made it into the Promised Land makes sense. They had relinquished all sense of ambition. The same subtle, attitude with which they fled the mountain of Hashem continued to accompany them further until the simple void of any optimism which was filled by dark cloud of negativity. The nation, in this setting, was no longer prepared to succeed, to submit itself to the Will of G-d. This was a nation prepared to give up.

TRAVEL GUIDE: “Vayehi Binso’a…”

All of the above leaves us with the remaining question. Why did the Torah insert the description of the Aron’s travels as the apparent signal to these issues, the tragedies surrounding it? Perhaps, because these verses hide the antidote to the problem.

“Vayehi Binso’a HaAron Vayomer Moshe Kumah Hashem Viyafutzu Oyivecha Viyanusu Misan’echa MiPanecha; U’Vinuchoh Yomar Shuvah Hashem Rivevos Alfei Yisrael”-“And it was when the Ark would travel, and Moshe said: ‘Arise, Hashem, and let Your enemies be scattered, and let Your haters flee from before You.’ And when it would rest, he would say: ‘Return [home], Hashem, [to, among the] myriads of thousands of Yisrael.’”3

What is being conveyed in in these verses? The Aron is traveling, symbolizing the finger of G-d pointing them in His direction.8 And who else but Moshe alone, speaking up in simple prayer to G-d each step of the way. When they traveled, he prayed that G-d eliminate the enemies in their path. And when the Aron stopped, when G-d’s Will allowed room for relief, Moshe’s prayer was simply that G-d rest His Presence among His people.

If one thinks about it, although these verses appear quite unassuming, they are quite profound, especially in contrast to the surrounding content. The B’nei Yisrael are concerned, rightfully so. The mission is not easy. It comes with challenges, obstacles, enemies, trials and tribulations. But how would they handle their mission? More importantly, what kind of attitude would they exhibit concerning their mission? Moshe, the leader of the mission, turned to G-d and simply requested that Hashem stand with them—“Kumah Hashem”—when they’d begin to travel and clear the path for them. When they’d receive a moment to relax, he requested that G-d do so with them—“Shuvah Hashem.”

There is nothing extraordinary here. And yet, it might make all the difference in the world! From the national standpoint, Moshe had the same mission that the people did, but Moshe did not create issues where there were none. Hashem would provide their food, clothes, direction, and anything else they might need. All Moshe prayed was that real threats, e.g. enemies, or any such force that will hinder their mission of serving Hashem, be removed from their midst, and for what? For the sake of G-d’s mission! And yet, even when there was no immediate threat of enemies and everything was okay, then too, Moshe faithfully prayed and requested that G-d remain among them for reassurance. “Just accompany us, Hashem,” he requested. Without losing hope, Moshe addressed the issue and put his faith in G-d, knowing that the mission can be accomplished.

Why didn’t everyone else do this? It was all a matter of attitude. Moshe was ready to succeed, albeit with G-d’s help, and albeit with real concerns to be dealt with. He was prepared to reach the final destination. The people, however, had given up before they had even begun. Their complaints were prefaced on their already made decision to give up. It was founded on an attitude of the feeling that they just wish they could be free from obligation, from the need to put forth any effort. That is why they failed. That is why the whole nation suffered. It became the reason why the whole generation had to forgo the opportunity to enter the Promised Land.

FINAL DESTINATION: The Right Attitude

Although it seems subtle, attitude is everything in life. Two people can look at the same challenge and it will be the respective attitudes that will influence one to strive and the other to fail. It’s attitude that will either stimulate one to turn to G-d for help or just complain. Attitude is evidently not just a difference between optimism and pessimism, or enthusiasm and disinterest, but is undoubtedly the difference between mastery and helplessness, between success and failure. In the Torah, it was the difference between the generation that made it to Eretz Yisrael and the one that didn’t, and it will be the difference between those who successfully follow Hashem all the way and those who won’t.

As attitude is the key to our destiny, it is up to us to determine whether it will open doors for us or lock them. If we follow the “Divine Editor’s note,” and develop the right attitude, the battle will already be won. We’ll undoubtedly succeed in our missions.

May we all be Zocheh to develop the appropriate attitude for all of life’s missions, enable ourselves to turn to Hashem for assistance and reassurance, ready ourselves to succeed in our Avodas Hashem, and Hashem should subsequently aid us in all of those missions, granting us the ultimate success as well as a swift entry into the Promised Land with the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg J

- Shabbos 115B-116A

- The above Gemara indicates that these verses actually belong somewhere in the description of the Digalim, or the divisions of tribes in their travel formation, perhaps either in Bamidbar 2 or just somewhere earlier in this Sidrah, namely in Bamidbar 10.

- Bamidbar 10:35-36

- Bamidbar 10:33. The nature of this tragedy is not spelled out explicitly, a point we will address shortly.

- Bamidbar 11:1

- 10:33

- Pirkei Avos 1:6

- In this vein, my Rebbi, R’ Yonason Sacks suggested simply that the Torah perhaps sought to highlight the stark contrast between the players of our two tragedies, the fugitives of Sinai and the complainers, and those who faithfully followed the Aron, using Hashem’s Torah as their guiding light.