| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein in Z’chus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandfather Moshe Ben Breindel, and my grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -Zalman Michoel Ben Golda Mirel -Ariela Golda Bas Amira Tova -And all of the Cholei Yisrael -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

Note: This is also a revision.

● What is the Significance of the Recurring Motif of Stones in Vayeitzei? ●

“The Role of the Stone”

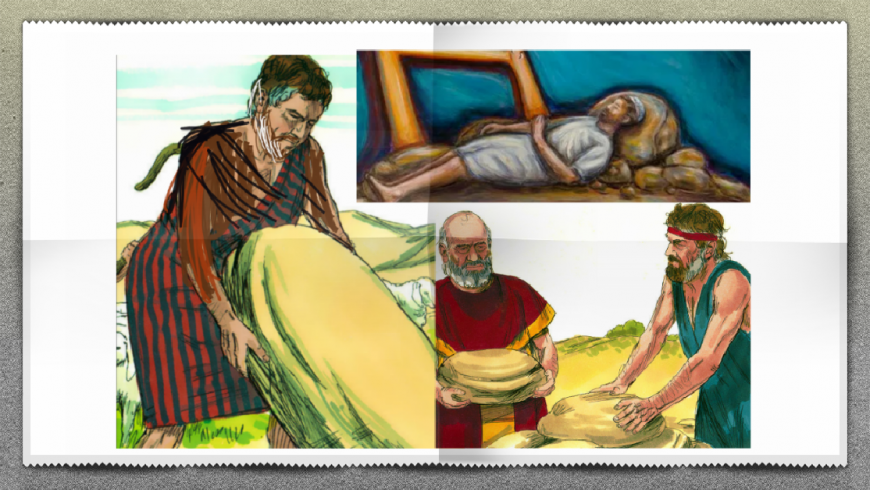

During Yaakov Avinu’s flight from Be’er Sheva where his begrudging and vengeful brother Eisav lies in ambush, Yaakov finds himself camping out in the middle of nowhere at which point he surrounds his head with stones to protect himself from the dangers of the wild. Afterwards, he has his well-known dream of the ladder to heaven and the prophecy of G-d’s assurance.

Certainly, there is a lot of significance to this dream, however, we’re going to now rewind a couple of shots back and focus on the stones.

Stone Scene 1: “The United Stones”

Now, concerning Yaakov’s arrangement of the stones, Chazal pick up on the fact that while Yaakov had set up multiple stones, as is suggested by the plural expression in the Pasuk, “Mei’Avnei HaMakom”-“from the stones of the place,”1 when he woke up, there was only one stone present—“HaEven.”2 Yaakov would ultimately dedicate this one remaining stone as a monument to G-d.

But, what happened to the other stones?

Rashi cites the famous tradition of Chazal that when Yaakov lay down to sleep, the stones began to quarrel, each arguing that the head of the righteous Yaakov rest on it, whereupon G-d miraculously unified them into a single stone.3 Thus, when Yaakov got up, there was only one stone.

Now, obviously the quarreling of the stones has deeper meaning. Perhaps this tradition intends a message conveying the importance of unity, particularly in holy pursuits; however, the question is why this lesson needed to be taught at this particular juncture, and through this particular analogy. Yaakov’s primary concern is that he reaches Charan in one piece. He is on the run and he is seeking shelter. He just wants to protect himself. While the lesson of “sharing is caring” is certainly an important one, is there not a more appropriate time for it than now?

Stone Scene 2: “Rock Well” (It was either going to be that or “Rock & Roll”)

Yet, the Torah has more to say about stones. In the very next scene, Yaakov arrives at a field where he sees flocks of sheep at a well waiting to be watered.4 He notices, though, that there is a huge stone over the mouth of the well and is told that until all of the shepherds have gathered together to remove it, no one is moving the boulder away. However, just upon the perfectly timed entrance of Rochel Imeinu, who would be Yaakov’s future wife, Yaakov would step up to the plate and roll the stone away so Rochel’s sheep could be given to drink.

Now, the simple question regarding this story is its necessity. Why is it recorded at all? Did the Torah merely need to record an anecdotal first meeting between Yaakov and Rochel? The Torah doesn’t just choose its scenes for the dramatic or romantic effect. Why do we care about Yaakov’s removal of the stone?

In this particular story, as was referenced, there is an echo of the previous account. That would be the stone. Yaakov’s heroic removal of the boulder from the top of the well is the undoubted focal point of the story, aside from the meeting between Yaakov and Rochel itself. But of what significance is this detail? Why was the stone conspicuously carried over to this narrative?

Stone Scene 3: “The Sorcerer’s Stone”

But of course, stones will make one final appearance towards the end of the Sidrah when Yaakov is finally permitted to part ways with Lavan, his uncle and father-in-law. After years of financial and emotional abuse from Lavan, Yaakov has had it and wants out. Yaakov attempts to flee Lavan’s home discretely, but Lavan’s divination informs him of Yaakov’s escape. When Lavan finally catches up though, Yaakov conveys his adamant intentions to return home, Lavan, powerless by G-d to stop Yaakov from doing so, attempts to bury the hatchet through a “treaty” with Yaakov.5

It is here where our motif resurfaces. Yaakov designates none other than stone monument for the treaty, just as he did earlier.6 Moreover, much like the stone from earlier in the Sidrah, this stone would actually become a mound made up of many stones as Yaakov gets his whole family to contribute stones to the pile. Together, this pile would serve as a boundary marker to stand in between Yaakov and his uncle/father-in-law.

What is the greater meaning of this stone monument? Being that this scene contains the second stone monument and the third mention of stones altogether in this Sidrah, the Torah’s fixation on stones at this time cannot be ignored. So, what truly is the role of “the stone” as it appears in this Sidrah?

Between a Rock and Hard Place

The broader meaning of the stones would seemingly have to do with Yaakov’s Divinely ordained mission. It’s all somehow necessary for him to experience and engage in right now. With that introduction, we’ll have to consider what that mission might be.

Concerning the first appearance of stones, we gave attention to the teaching of Chazal that the group of stones fought for the rights to serve as Yaakov’s pillow but miraculously became one. We mentioned that the message was one conveying the importance of unity and coming together. We were troubled simply by the question as to why this message relevant for Yaakov at this point in time?

If one thinks about it, perhaps G-d’s intention was for Yaakov, amidst his escape from his homeland, to understand what went wrong back there and to ultimately learn the way to rectify whatever blemishes existed in his past, for better or for worse. Firstly, Yaakov has a brother who wants to kill him, and secondly, he’s now assuming not only his own spiritual responsibilities, but those of his brother Eisav who had fallen short. On the run, it is perhaps important for Yaakov to understand (1) why Eisav is on his tail, and (2) why he must succeed his parents alone, without Eisav, and (3) how he can do so properly.

What went wrong at home? Why does Eisav want to kill him? Without reviewing the whole story, Eisav’s feud with Yaakov is over personal legacies and inheritance. There is hatred and contention between the brothers.

Now, why can’t Eisav continue the spiritual revolution of his family alongside Yaakov? Because of the same problem—contention. Many suggest that while Yaakov was originally intended to provide spiritual service from the tents, Eisav was supposed to provide the material serve of G-d in the fields of the outside. However, because of the lifetime of contention between two brothers and seemingly zero attempts to alleviate that contention, the brothers worked alone were forced to either sink or swim. Eisav sank. Accordingly, Yaakov must swim for the two of them as he proceeds to fulfill Eisav’s role as well.

What would this new dimension of Yaakov’s mission entail? Ironically, it entails the same kind of measures that might repair his family issues. He would observe and learn, from other points of view, what interpersonal relationships look like when there is friction versus harmony. He would have to engage with others in society. He would develop a stronger sense of camaraderie.

So, where do the stones come in?

Stones of Contention

The stones represent the hearts of contentious, divided individuals. There is a rough surface that naturally separates individual stones. They are naturally divided. There is no less a natural coldness that separates man from his fellow. This contention is present in each of the stone scenes.

- The United Stones

Yaakov puts the stones around his head as he anticipates the challenges that come with going out into the world and dealing with others. He’d rather stay in his own tent and do his own thing. And perhaps the stones felt the same way—“every man for himself.” Yet, they came together to serve Yaakov. They defied nature and merged. In the same vein, Yaakov will have to learn how to breed a family that breaks the barrier of natural competition, merging for a common higher purpose and not, Chas Va’Shalom, fighting with one another in pursuit of that higher purpose.

- The Rolling Stones (I Couldn’t Resist)

Now, Yaakov has left home in Be’er Sheva, leaving the comfort of home, as he enters the outside world originally prescribed to Eisav. Interestingly, these two factors would seem to come together in the second scene of our Sidrah. According to the story, Yaakov enters the “field,” which we know, is Eisav’s terrain.7 Indeed, he’s in the outside world where society is impossible to avoid. He has to engage with fellowman. And what would he find there? He happens upon a “Be’er,” a well, perhaps a resemblance to his home, Be’er Sheva (which, in fact, was named after wells).

And this “Be’er,” quite like Yaakov’s home, is being blocked by a “stone” representing the obvious contention. Indeed, the stone in this very scene represents contention as the shepherds would routinely block off the well so that no one of them could ever take water from the well unsupervised by the rest of the group. There was a natural fear that someone might take more than the fair share. The concern is a fair one, considering the naturally selfish mindset of the individual. It’s the same obstacle of natural contention between people.

So, how can Yaakov successfully retrieve the water from the Be’er? How can Yaakov safely return home to Be’er Sheva? He has to somehow remove the obstacles that block the “Be’er”—he has to eliminate the sources of selfishness and contention.

- The Sorcerer’s Stone

How relevant these lessons would be, not just for Yaakov’s past, but for his future. After these two scenes, Yaakov runs into the Lavan problem. Lavan epitomizes greed and selfishness. He goes through every effort to earn a buck off Yaakov. Indeed, Lavan breeds contention in Yaakov’s family and breaks the sense of oneness. He turns his own daughters into rival wives by cunningly marrying off his other daughter to Yaakov before allowing him to marry the one whom he had an expressed desire for—just so Yaakov could work for him longer. The rest of Yaakov’s hardships in life are going to be centered on the major feud between the sons of his two wives, bred by natural contention in the house of Lavan. In Lavan’s world, everyone is firmly for themselves, like divided stones.

But, in the last account of the Sidrah, Yaakov and Lavan are actually coming together for a treaty. Now, there are two types of treaties; one is of pure peace and goodwill—like most of the treaties Hashem makes with man.8

The other type of treaty appears here. The context will reveal that this “treaty” is none other than an attempt at nonviolent agreement to disagree. There is looming hostility. Yaakov and Lavan do not like each other. Yaakov tried to live with him on good terms, but Lavan is a self-centered lowlife. It is no wonder why Yaakov uses a stone monument to divide himself from the likes of Lavan, the master of natural selfishness. Thus, Yaakov’s stone reflects the contention that was ultimately a product of Lavan’s own creation.

However, interestingly, Yaakov’s stone monument is not enough. Aside from Yaakov’s monument, the Torah testifies that Yaakov tells his “brethren” (“Echav”) to collect stones as well, and they make a pile.9 This pile is what’s known as the famous “Gal’eid,” literally, “mound of testimony” (referred to by Lavan in the Aramaic, as “Y’gar Sahadusa”). Now, why does this treaty require this pile of stones?

Furthermore, Rashi, based on the Midrash, points out that when Yaakov told “his brethren” to collect the stones, he was actually addressing his sons, yet the Torah describes them here as his brothers, as if to ascribe to them a hint of brotherliness which they displayed towards Yaakov in the way approached him, as if supporting him in a time of communal pain or war.10

So, what does this really mean? Would a person’s own sons not also come to his aid at such a time? Why does the Torah have to refer to Yaakov’s sons as “his brothers” if it would actually make better sense to call them “his sons”?

For Sons to Be “Brothers”

To understand both of these issues, one has to return to the greater picture we’ve painted. Firstly, concerning the pile of stones, one can’t ignore the resemblance it shares with the stones in the beginning of the Sidrah. These stones, like those around Yaakov’s head, are coming together to form a single unit. And perhaps this connection contains the deeper meaning behind the Torah’s odd description of Yaakov’s sons as “his brothers.”

One might suggest that Yaakov’s sons—although his they’re certainly his sons—are not all actually brothers. Consider the fact that many of them were born from different mothers. As per their situation, they were naturally divided. Little does Yaakov know what we e know from history, that there would be times when the contention between the brothers will tear them a part, and some, even away from their own father. However, perhaps here, Yaakov lays out his desired framework for how his sons should be with one another. He wants them all to come together like brothers—brothers to each other and perhaps even with Yaakov as well.

Indeed, just as stones around Yaakov’s head let go of the contention and united, so should Yaakov’s sons. And just as Yaakov looked at what was necessary for the greater good and exerted himself to roll the stone away—removing the barrier of contention, he commands his naturally divided sons to act accordingly. Yaakov thus stresses their need to contribute to the “pile” in order to come together, remove the barriers of contention and social adversity among themselves, which was created by Lavan.11

What more could a father want from his children, than to be each other’s brothers?

For a greater cause, all of them will be like the united stones of Yaakov’s past, like brothers coming together at a time where everyone needs one another.

With these lessons internalized, with these obstacles hopefully conquered, Yaakov can return home to Be’er Sheva. With the new perspective of father, Yaakov can truly appreciate and internalizewhat the contention between him and his brother looks like. Yaakov hopes to leave behind all contention when he reunites with Eisav. The question is if Lavan’s counsel will cross over to Yaakov’s domain. Have the damages of Lavan’s greedy ideologies and disregard for fellowman already been done?

As was mentioned, history will reveal that this force of natural contention between brothers, as represented by simple stones, will come back to haunt Yaakov and his sons. Moreover, this contention has been Am Yisrael’s greatest enemy in history. In our generation as much as any other, if not more, our nation suffers from enmity, yes from the surrounding nations of the world, but more so and more painfully from within its own people. It is this unhampered contention which breeds the Sinas Chinam which has contaminated our nation and makes our people prone to the terrors which the world subjects them to. The only solution is to take the lesson of the stones under Yaakov’s head which defeated contention and unified for G-d’s Will. The answer is to remove the stone of contention from the wells in our path. The only way is to be like brothers, coming together, despite differences, because G-d knows we need each other now more than ever.

May we all be Zocheh to eliminate all hostility and contention from within our people, selflessly come together as one unit according to the higher Will of Hashem, be shielded from the enmity of the surrounding nations, and our oneness should usher in the arrival of the Geulah with the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Bereishis 28:11

- Ibid. 28:18

- Chullin 91B

- Bereishis 29:2-10

- Ibid. 31:44-54

- Ibid. 31:45

- Ibid. 25:27

- See Hashem’s treaties with Noach [Bereishis 8] and Avraham [Bereishis 17].

- Bereishis 31:46

- Bereishis Rabbah 74:13

- Interestingly, the word which the Torah uses for Yaakov’s removal of the stone of contention, “Vayigal”-“and he rolled,” has the same letters as the word used to describe the pile which brings the brothers together, “Gal”-“pile/mound.”