| This D’var Torah is in Z’chus L’Ilui Nishmas my sister Kayla Rus Bas Bunim Tuvia A”H, my maternal grandfather Dovid Tzvi Ben Yosef Yochanan A”H, my paternal grandfather Moshe Ben Yosef A”H, uncle Reuven Nachum Ben Moshe & my great aunt Rivkah Sorah Bas Zev Yehuda HaKohein. It should also be in Zechus L’Refuah Shileimah for: -My father Bunim Tuvia Ben Channa Freidel -My grandmothers Channah Freidel Bas Sarah, and Shulamis Bas Etta -MY BROTHER: MENACHEM MENDEL SHLOMO BEN CHAYA ROCHEL -HaRav Gedalia Dov Ben Perel -Mordechai Shlomo Ben Sarah Tili -Yechiel Baruch HaLevi Ben Liba Gittel -Noam Shmuel Ben Simcha -Chaya Rochel Ettel Bas Shulamis -Nechama Hinda Bas Tzirel Leah -And all of the Cholei Yisrael, especially those suffering from COVID-19. -It should also be a Z’chus for an Aliyah of the holy Neshamos of Dovid Avraham Ben Chiya Kehas—R’ Dovid Winiarz ZT”L, Miriam Liba Bas Aharon—Rebbetzin Weiss A”H, as well as the Neshamos of those whose lives were taken in terror attacks (Hashem Yikom Damam), and a Z’chus for success for Tzaha”l as well as the rest of Am Yisrael, in Eretz Yisrael and in the Galus. |

בס”ד

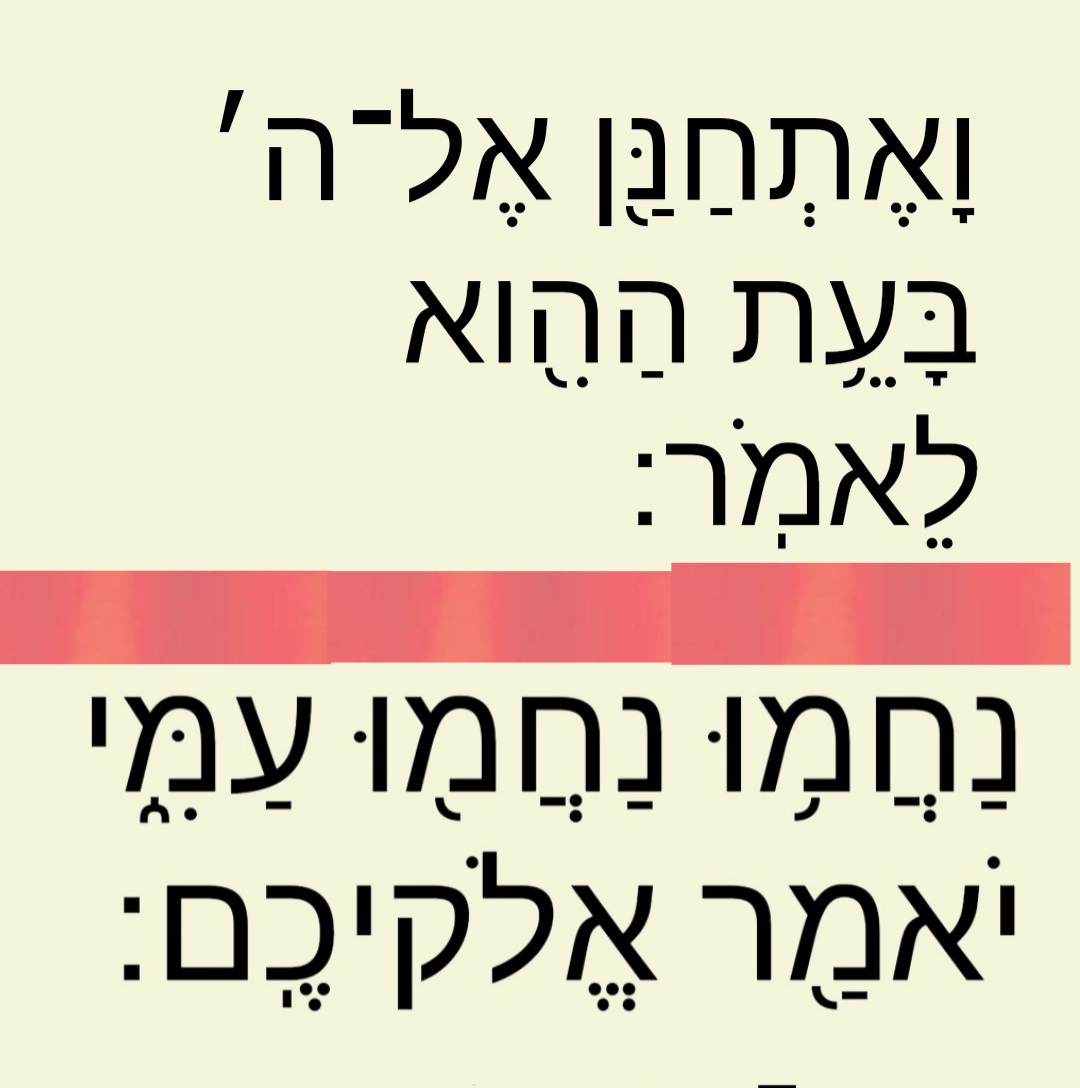

וָאֶתְחַנַּן ● Va’Es’chanan

נחמו שבת ● Shabbos Nachamu

The Shabbos of Parshas Va’Es’chanan always takes place right after Tish’ah B’Av, and is known as Shabbos Nachamu [נחמו שבת], named after the opening words of the Haftarah which is taken from Sefer Yishaiyah1, where the Navi calls out in the Name of G-d: “Nachamu Nachamu Ami…”-“Be comforted, be comforted, My people…”

The basis for the selection of this Haftarah, and really the simple meaning of this Haftarah altogether, is that despite the fact that the nation currently lives in state of exile and destruction—which we nationally mourn on Tish’ah B’Av—Hashem encourages us, “Nachamu,” be consoled or comforted, because the destruction is over, good tidings of the redemption are on their way, and soon, G-d’s glory will be revealed to the world.

Indeed, one of the themes on Tish’ah B’Av, as highlighted by the recurring phrase in the first chapter of Megilas Eichah, “Ein Menacheim [מנחם]”-“there is no source of comfort,”2 is that there is an aching lack of Nechamah [נחמה] as a result of the Churban Beis HaMikdash, the Destruction of the Holy Temple, and the Galus or Exile overall. Surely, after a discouraging and heart wrenching Tish’ah B’Av, the idea of having comfort certainly should be comforting, to say the least. Anytime someone has lost something or someone he loves, or whenever one has his dreams ruined before his very eyes, or in this case, when we have tirelessly yearned for the ultimate redemption but another Tish’ah B’Av has gone by and we continue to live in exile, of course, there is a desire to gain that Nechamah, that sense of comfort.

The question is: How does one achieve this Nechamah? Suppose Tish’ah B’Av has passed us by and we have read the words of the prophet saying “Be comforted.” For anyone who is actually depressed about the Destruction and Exile, what does that actually help? Have the facts changed? Is the Beis HaMikdash no longer in ruin? Has Israel finished suffering at the hands of its oppressors? Do we no longer reside in Galus? Most years, the answer to all of these questions is “No.” There is still loss. The Geulah that we like to fantasize about has still not arrived. Moshiach hasn’t come. So, what has changed? That the day of Tish’ah B’Av is over? That a mere calendar date has come and go? All that means is that we’re allowed to eat and listen to music again, but what practically has changed with the current circumstances? Nothing at all. Why then, or how, in this continued state of exile, could we suddenly be comforted by the words of the prophecy which still hasn’t come to be in our time? How can one achieve this Nechamah?

Moshe’s Broken Dream

As we turn over to the actual Sidrah, we might notice another individual who experienced a similarly painful challenge relating to perpetual exile and the inability to “return” to the Holy Land.

Moshe Rabbeinu, continuing his discourse to the B’nei Yisrael, proceeded to relate how he implored Hashem to allow him to enter the Promised Land, and how Hashem ultimately denied his request and withheld him from fulfilling that one dream he had.3 Yes, Moshe Rabbeinu had made a mistake by hitting the rock at Mei Meirvah instead of merely speaking to it to obtain water, and yes, Moshe, at that moment, failed to sanctify G-d’s Name by fulfilling G-d’s command, but of course, one cannot help but sympathize with Moshe. It’s an undeniably sad situation. Here, we have Moshe Rabbeinu, the greatest man to ever live, who devoted his life to the service of Hashem and Hashem’s people, and the one thing he ever wanted for himself, Hashem has decreed that he will not be able to achieve. Moshe didn’t even care to continue leading the people. He had already appointed Yehoshua to do that. All he wanted was to enter the Holy Land once before he’d die. But, no—Hashem had forbidden him from doing so. Moshe would finish off his time in this world in the state of exile. He would not see the fruits of his labor, nor the completion of his mission. He would not witness the full Geulah in his times.

Certainly, this part of Moshe’s speech carries a lot of emotional weight, but a simple question one could ask here is why it was important for Moshe to mention these points—that he prayed to G-d to let him enter the land and that G-d said no? Is it our sympathy Moshe was looking for? Was he just getting emotional as he prepared to die while the people enter the Promised Land without him? Maybe, mentioning these points was Moshe’s way of segueing into the topic of the B’nei Yisrael entering the land, as he was about to teach them how they should act so that they could succeed in the land. Perhaps he was trying to show the people how just fortunate they were that they would eventually enter the Promised Land, because he wouldn’t be doing the same. While the above is all possible, bear in mind that the people all knew by now that a whole generation before them, their own parents, lost their rights to enter the land. They didn’t need Moshe to explain his own unfortunate situation to them. Moreover, when we get to the core of this issue as it is presented here, it really was Moshe’s personal problem. Yes, it’s a saddening problem with which we can identify today, but at that moment, it was Moshe’s own issue. Why really did Moshe feel the need to talk about his desperate and ultimately rejected prayer before G-d?

The Meaning of “Nechamah”

Before we can answer the original question, how we can attain Nechamah on Shabbos Nachamu despite continually living in exile, we have to first consider the premise of the question itself.

Correct, we’re still in that state of Churban, and while in that state, it is hard to actually feel comforted. Apparently though, the Navi urges us, “Nachamu,” implying that somehow, there is some means for us to feel this Nechamah. Now, what we can’t quite wrap our heads around is how we can truly feel comforted if we’re still suffering. Indeed, what would make one really feel comforted would be if the suffering ended and Moshiach would come right now. Since that is not the case, we need to know how it is possible to truly have comfort while we’re in Galus.

Now, if we assume that “Nechamah” purely means “comfort” as it is colloquially understood, then it certainly is hard to feel “comfortable” in a state of brokenness. But, maybe Nechamah is not entirely what we think it is. If we’re expected to achieve Nechamah even while we’re in this state of suffering, maybe there’s more to Nechamah. With that in mind, what does it mean to achieve Nechamah?

Typically, Nechamah is translated to mean either comfort or consolation. However, the root word’s connotations, at least, as per its first unmistakable appearance in the Torah, seem to have nothing to do with comfort. As G-d prepared to destroy the world because of the corruption in mankind, the Torah relates, “Vayinachem [וינחם] Hashem Ki Asah Es HaAdam BaAretz Vayis’atzeiv El Libo,”4 which we would seem to reasonably translate to, “And Hashem regretted that he made man on the earth and He was saddened toward His heart.” Indeed, at least at first glance, it would not make sense, in this context, to suggest that Hashem was comforted about the fact that He created man and that He was comforted that mankind had become corrupted. The connotation of regret seems to be the simplest reading.

The obvious problem though is that comfort and regret are basically complete opposites of one another. Comfort refers to a positive state where one is accepting or even relatively content with the current state. Regret is undoubtedly a negative emotion where one no longer approves of the situation and is unhappy about it. So, which one is it? How can Nechamah mean both comfort and regret? What does Nechamah actually mean?

Nechamah as “Reconsideration”

If one thinks about it, there is a common denominator between comfort and regret, namely, the fact that they are both emotions of a second thought—reflecting and rethinking about an earlier perceived notion or opinion about a given circumstance. When one regrets something, he looks back at a decision he once approved up in a new negative light. When one is comforted about something, he looks back on a reality he once bemoaned in a new positive light. Thus, the root of “Nechamah” accurately means and would be better translated as reconsideration, whether for the better or for worse.5

Thus, Nechamah, as we can better understand, really has to do with our personal outlook of the situation. When we thought the situation was good, Nechamah or “reconsideration,” can come along and cause us to regret the situation. And yet, when we’re in a state of Churban and Galus, when the situation looks utterly terrible and hopeless, Nechamah can come along and bring us comfort, letting us know that despite the situation, there is some hope and we therefore can go on. Nechamah, in this way, enables us to move forward.

Indeed, the situation still has not changed. When someone loses a person, Nechamah does not mean that person is suddenly revived. Of course, when a person fulfills the Mitzvah of Nichum Aveilim, comforting mourners, he does not bring the dead back to life, something that no human can do. The idea of providing Nechamah for a mourner is to help the mourner digest the reality of his situation, reflect on the situation and relate to it in a new way. Similarly here, there might still be exile and pain—that much hasn’t changed. But, Nechamah provides us a new and calmer way of coping with and relating to that pain so that we can keep going in life.

Nechamah in Galus

We asked before why we should be comforted after Tish’ah B’Av. Well, we could’ve really asked the question in the reverse. Why should we even fast and mourn on Tish’ah B’Av at all? Yes, Tish’ah B’Av is the day of mourning, but, why is just this one day? Galus as we know it exists every day and that would remain the status quo until, of course, the Geulah arrives. In the meantime, the Temple had not been rebuilt the whole year prior to Tish’ah B’Av, and it is still not built at the current moment. Why don’t we continue mourning and fasting every single day? The answer is that really, we should! But we don’t, because, G-d knows we can’t do that. Of course, we could not survive fasting every single day, but more than that, we could not functionally live life that way, wallowing in our sorrow, doing nothing but perpetually mourning and feeling hopeless every single day. We will never be able to accomplish anything that way. However, once a year, on Tish’ah B’Av, we can face the current reality that exile still exists and we can mourn—because, yes, it hurts, and yes, we should feel dejected and rejected about that reality. But, even with the reality of death, broken dreams and failure, we do not eternally lose hope. We need to reach Nechamah, to relate to the reality in a way that will allow us to roll up our sleeves and continue life.

But, what could we possibly do next if our dreams have been crushed, if our loved one has left us? How many people and generations yearn for redemption and pass on before they can get the chance to see it in their lifetime? How many people need to die before they could ever get the chance to even enter the Holy Land of Israel? What can be said for all of the deceased? Life doesn’t seem to go on for them. And what if, G-d forbid, that reality becomes our fate? What if one knows that he personally won’t be around to experience redemption as it unfolds? What if he knows that his own dreams will never come true in his lifetime? How would he continue living each day of his life? What goal could he possibly have left at that point? How does he develop Nechamah then?

Moshe’s Model for Nechamah

Moshe Rabbeinu, as he stands before us in Va’Es’chanan, teaches us the answer to the challenge of Nechamah. He knew unequivocally that he would never accomplish the one thing he desired. He knew without doubt that his personal concept of self-actualization—entering the Holy Land with the B’nei Yisrael—would not happen. He worked toward that goal; he prayed for it, he yearned for it. He wanted to see the redemption in his lifetime. But as it was for his siblings, death in the state of exile would become his reality. Moreover, he knew that for his purposes, that reality was unchanging. This much we know from Moshe’s story at the beginning of the Sidrah. What could Moshe possibly hope for?

And yet, what does the Torah tell us next? What would Moshe do for the rest of the duration of the Sidrah? He would proceed to remind the B’nei Yisrael, the next generation, of their responsibility in their service of Hashem. He reminds them that “Hashem Elokeinu Hashem Echad”6—that Hashem is he One and Only Trustworthy G-d and that “Ein Od Milvado”-“there is none beside Him,”7 that they have love G-d with all their heart and all their soul no matter what happens to them.8 In that same vein, we have to remember that it Hashem took us forth from Exile once before and that Hashem will undoubtedly redeem us and bring us back to the Promised Land!

Moshe Rabbeinu, more than anyone else, had the right to be upset and disheartened—his dreams wouldn’t be fulfilled. But he rolled up his sleeves and continued to do the real job he was put here for—the same job each one of us were put here for—to serve G-d to the best of his abilities. Of course, we would love and we yearn for the Geulah to come as soon as possible. Of course, we pine to return to the Holy Land. Yes, it should come speedily in our days. But, our real goal should be the goal that is ever present before us, the one dream that we can fulfill each day no matter what, the goal of loving and serving G-d with our entire essence. Moshe Rabbeinu wanted all the same things, and even if his personal hopes were lost, he did not give up on Hashem or himself. He allowed himself to continue to lead the B’nei Yisrael and teach them how to be Ovdei Hashem or servants of Hashem until he could do so no longer.

The State of True Comfort

Yes, even in Galus, in the state of Churban, even if all hope seems lost, we too can and must continue this mission. But, we can only do so once we’ve allowed ourselves to receive that Nechamah, the true sense of comfort or reconsideration. That new perspective comes, not from a magical change of circustance, but from the knowledge and acceptance that no matter what happens, we still have a mission to complete as long as we’re still here, and that that mission will lead us to our destiny. We can achieve this true sense of comfort if we realize that G-d is in charge and that there is no one besides for Him. We have to know that because Hashem runs the show, that means that in the end, everything will be okay as long as we do our part, pick ourselves up and try our best moving forward.

May we all be Zocheh to achieve that true sense of Nechamah, realize that we still have to complete our mission of devoting our lives to Hashem and Klal Yisrael, complete that mission, and Hashem should reveal His glory to us and the world once again in the form of the ultimate Geulah, the rebuilding of the Beis HaMikdash, and the coming of Moshiach, Bimheirah Biyomeinu! Have a Great Shabbos Nachamu!

-Yehoshua Shmuel Eisenberg 🙂

- Yishaiyah 40:1-26

- Eichah 1:2, 9, 16, 17, 21

- Devarim 3:23-26

- Bereishis 6:6

- See Rashi’s comments to Devarim 32:36 where he defines “Nechamah” precisely this way.

- Devarim 6:4

- 4:35

- 6:5